In the line of fire: Garden design to reduce the threat of bushfire

Increased risk of bushfire may be the new normal in many parts of Australia. Still, there are plenty of things you can do in your garden to give your house a better chance of survival if a fire does hit. Landscape architect and bushfire consultant Anthony Power explains the science behind fire and gives some practical advice for garden design.

Last summer, Australia experienced one of the worst bushfire seasons in its history. More than 12 million hectares (an area almost twice the size of Tasmania) burnt across the country. During these times, many of us look at what we can do to reduce our bushfire risk.

Landscaping is not often the first thing people think of to improve their property’s chances of survival in a bushfire. However, good landscape design and garden construction can play a significant role in reducing the probability of house loss or damage. There are many creative landscape solutions and ideas to improve the chances of bushfire survival. The size of the garden, its climate zone, its intended use and other factors will have a bearing on the strategies available. In this article, I want to introduce the science behind fire behaviour and how it relates to gardens and house survival, and provide an overview of those strategies.

Let’s first dig into some basic fire behaviour concepts.

Understanding basic bushfire behaviour

Combustion is a chemical reaction that converts fuel energy into heat, light and particulates (smoke). The heat from the flame is transferred to nearby fuels until they too ignite, and the cycle continues; breaking this cycle stops the spread of fire. Plants are the primary fuel source in bushfires. The nature of the fuel has a strong influence on how it burns and subsequently, fire behaviour. Some plants ignite quickly, while others may burn slowly or incompletely.

Invented in the 1960s by American fire scientist George Byram, ‘fire intensity’ is a term frequently used to describe bushfires. It is a measure (in kilowatts per metre of fire front) of the energy release of a fire through the combustion process. Fire intensity is calculated by multiplying the amount of fuel consumed (in kilograms per square metre), the heat yield of the burning material (in kilojoules per kilogram), and the fire’s rate of spread (in metres per second). Understanding this basic equation is useful as it can help inform our garden design.

Research on the heat yield of different plant species is somewhat lacking. However, we know that increasing the moisture content through regular watering reduces the heat yield as the fire must burn off the moisture in the fuel before combustion can happen. Some fuels may even be unavailable to burn if their moisture content is high enough. Water vapour in the fuel reduces the radiant heat output, which is a crucial mechanism in fire spread by drying and preheating fuels ahead of the flames.

Topography and wind are the primary mechanisms that drive a fire’s rate of spread. They can also act together to funnel fires along gullies, around hills, through gaps in trees and so on. Wind also plays a vital role in fire spread by transporting firebrands and embers.

Ember attack is the primary cause of house loss to bushfire in Australia, accounting for over 80 per cent of recorded losses. Ember density is highest near the bushland edge. Embers land on and can ignite houses, gardens, mulches, garden furniture, cars, outbuildings, mats, lawns, pergolas and so on. They can be trapped and accumulate against vertical surfaces, particularly in corners of buildings. Other bushfire attack mechanisms on houses include direct flame contact and radiant heat flux.

So, to reduce possible fire intensity and risk to our homes, we can focus on reducing:

- the amount of available fuel in our gardens

- the heat yield of the vegetation

- the fire’s rate of spread by reducing wind speed and possibly modifying the slope

- the possibility of flame contact with our house

- the level of radiant heat flux impacting our house

- the number of burning embers that can reach our home.

These are all factors which we can influence through the design and construction of our gardens. Now let’s move on to an overview of design strategies to implement around your home.

Understanding your site and its position in the landscape

Some places are more prone to fire than others. Whether you live in a rural or bushland area, a small town or a peri-urban area, it’s a good idea to assess your site to gain an understanding of its level of bushfire risk. Influencing factors include climate, slope and aspect, density and type of surrounding vegetation, distance to bushland, and likely direction for bushfire attack. The site’s position within the landscape such as on ridgelines or at the bottom of slopes as well as the property’s distance to roads and avenues of escape all play a role. Arranging a visit from your local fire authority or an accredited bushfire consultant is an excellent place to start.

One factor to understand is the likely ‘fire wind’ direction. Although wind can move fires in any direction and topography also has an influence, in any location there are typical wind directions that are associated with bad fire weather. These usually involve dry winds emanating from the hot and arid interior of the continent. On the eastern seaboard of Australia, fire winds typically come from the west. In Western Australia, the reverse tends to be the case with hot, dry winds blowing from the east. By contrast, winds with a maritime influence are more cooling and tend to carry higher levels of moisture. Consideration must also be given to the direction of a potential wind change. In southern Australia, bad fire weather is associated with winds blowing from the north-west. A wind direction change from the south-west will often follow in the evening. The long northern flank of the fire can then become the head of the fire, creating dangerous fire behaviour.

Forest fires will behave differently to heathland, woodland or grassland fires. There is also variation in fire behaviour between small and large patches of vegetation.

Creating defendable space

Now armed with a better understanding of where fire obtains its energy for combustion and something of the way it attacks houses, we have a few principles with which to design our gardens. Good design will help create ‘defendable space’, reducing fire intensity and the risk to the house. These include layout decisions, material choices and plant selection. Providing sufficient water supplies to maintain high moisture content in your plants is also important.

Islands of fuel

When it comes to planning your garden layout and plantings, physical separation of patches of vegetation reduces the overall fuel load in your garden and also a potential fire’s rate of spread. Consider arranging plantings in your garden as ‘islands’ in a ‘sea’ of non-combustible or very low fuel areas. The ‘sea’ can be areas of gravel, mown lawns, driveways, ponds or even sections of garden dominated by plants with high moisture content such as succulents.

And it’s not just the plants. Identifying other potential fuels – organic mulches, unprotected sheds with flammable contents, outdoor furniture, bins, wooden fences, stockpiles of timber, timber retaining walls and so on – and keeping them away from the house reduces their potential attack on the house as secondary fires and is critically important. Some of these sources of fuel may burn for long periods once ignited.

In particular, keep in mind that burning wooden fences may lose structural integrity and fall against the house if they are close enough, creating an enduring source of embers, heat and flame.

Radiant heat barriers

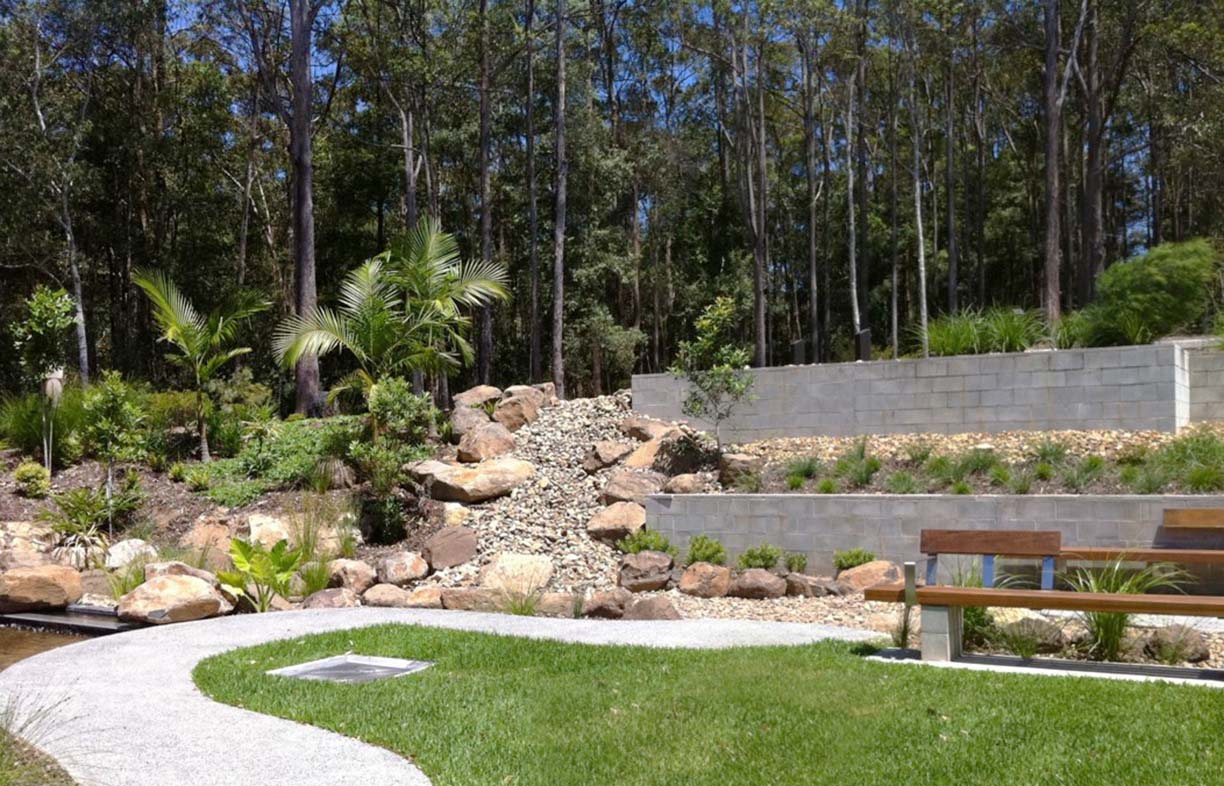

Barriers such as non-combustible garden walls, fences and even less-flammable tree species can provide a filter and obstacle to the passage of fires and embers. They can be useful in slowing the spread of fire. They also serve to shield objects behind them from radiant heat.

However, if these barriers ignite, they can become part of the attack on a house. Radiant heat barriers should, therefore, be placed with care if they are themselves combustible. As a rule of thumb, keep them two times their height away from the house. Non-combustible materials like rock and masonry are excellent for retaining walls and other garden features designed to double as radiant heat shields.

Plant selection

Careful plant selection and placement can reduce both the amount of fuel in our gardens and its heat yield. Things to consider when choosing species include a plant’s moisture content, volatile oil content, size, shape and habit. See facing page for more on plant considerations and high- and low-risk plants for bushfire-prone gardens.

Keeping water on hand

Water is the antithesis of fire. Maintaining a high moisture content in plants surrounding your home reduces their flammability and the intensity when they do burn. It will increase the chances of building survival if a bushfire strikes. Maintain high moisture levels before and during the fire season, particularly around the home. A green lawn will not only be less flammable but will also keep the area around your home cooler. Similarly keeping up the moisture to plants will prevent them from wilting and producing dead material which is much more flammable than living green leaves, stems and branches.

Water is also valuable for firefighting and may be used to actively defend the home. Consider installing water tanks dedicated to firefighting, even if you are on town water; your local fire authority may well require this for properties over a specific size. A swimming pool (perhaps a natural pool!) is also suitable for this. Automatic drenching or sprinkler systems to protect the house are excellent if designed, installed and maintained correctly.

Access for effective firefighting

Whether you choose to stay and defend your home during a bushfire or leave, easy access to and around the property is critical. Design clear vehicle and pedestrian pathways to help protect your home, for escape and for access to water supplies. If possible, provide sufficient clear turning space for fire trucks. Narrow pathways for firefighters to run hoses down the sides of suburban allotments may be blocked by fire if the fences are flammable. If this describes your situation, consider replacing the flammable fence with a non-flammable one such as Colorbond.

Conclusions

To summarise, I recommend that you have a look at your property, and ask what type of bushfire attack am I likely to experience? Are there areas or directions from which my house is particularly vulnerable? Do I have a defendable space around the house? Would some areas around my home provide a significant source of fuel for a fire? Is there an opportunity to trap or filter embers or shield the house from radiant heat? Do I have enough water? Could a fire crew safely drive a 4WD truck in, or at least run a hose? Are there paths of escape for me, my family and firefighters and do I have enough gates?

Bushfires behave according to scientific principles; therefore, their effect on buildings and gardens is predictable. We can increase the resilience of our homes by using Byram’s fire intensity equation in our favour. This includes increasing environmental moisture, avoiding the placement of flammable material near our homes, reducing and arranging fuels to impede the spread of fire, and reducing the wind speed and rate of spread of the fire with barriers. Including objectives for bushfire protection is part of good landscape design and should be considered early in the design process.

Plant consideration

Given the right conditions, all plants will burn. However, we can choose plants for their ability to survive a fire as well as their fire-resistant qualities. Plants with a higher water level in their leaves will resist fire for longer than those that are ‘thirsty’.

Bushfires usually occur on hot and windy days when there is low humidity, sometimes after a long period of extreme heat and no rainfall. During times like these, large plants can lose hundreds of litres of water a day through transpiration. If water is available, try to ensure your plants are well watered during these occasions – especially if a fire has the potential to spread to your area. Watering may save the plants from catching alight, and the wet ground will reduce the potential of embers setting leaf litter or mulch on fire.

Find out which plants help prevent the spread of fire, and which plants are highly combustible. Unfortunately, many of our favourite Australian plants are flammable for various reasons, including the fact that they have a high oil content. Low-flammability ground covers can help reduce the spread of a ground fire, especially if they have been recently watered. Whether or not you are in a fire-prone area, you should take the time to learn the legal requirements of what can and can’t be planted in and removed from your garden.

In high-risk areas for fire, it’s sensible to have a plant-free zone near the house. This reduces the chance of the house catching fire and also allows easy access in and out. People living in the bush, however, generally enjoy the look of plants close to the house. If this is you, be careful about what you plant and where. Planting under windows or near doorways is a risky move. Not only can the plants ignite, potentially setting the house on fire, but if organic mulch is used, this can also begin to smoulder. Container gardens are a good choice if you yearn for plants near the house, as they can be moved during the bushfire season.

Don’t plant trees close to the house, because their branches may overhang the building when the trees are mature. When planting trees, space them so that when they’re mature there will be a gap of 2–3 metres between the foliage. This can help prevent the spread of fires that are ‘crowning’ (moving through the canopy). It is also a sensible approach for large shrubs. Reduce the number of areas that contain low plants and taller shrubs under trees, as a ground fire will quickly climb up into shrubbery and then into the trees if foliage is overlapping. Alternatively, remove a tree’s lower branches.

High- and low-risk plants

It can be difficult to work out which plants are considered highly flammable and which are deemed to be low risk. Confusion seems to centre on the shape and habit of a plant rather than the type of plant. For example, some people feel that dense plants won’t burn as easily as open-branched plants, because embers won’t penetrate them as readily, while others argue that dense plants should be considered high risk because they contain a large proportion of dead material within them and therefore will ignite quicker than a plant with an open habit.

What isn’t in doubt, however, is that plants with a high oil content and thin hard leaves – such as those in the myrtle (Myrtaceae) family (for example, Eucalyptus, Callistemon, Leptospermum, Syzygium, Darwinia, Melaleuca and Thryptomene species) – are much more flammable than plants with fleshier leaves that have a higher water content. This is because the ignition point of oily plants is lower than that of water-filled plants.

Water-storing succulents are renowned for their unique fire-retardant capabilities, but Australia is not known for succulents that are suitable as garden plants. Nevertheless, there are quite a few varieties that will happily exist in the home garden if the conditions are right, including Carpobrotus, Calandrinia, Disphyma and Portulaca species. Some are suitable for ground and container planting, so could be a savvy option for using close to the house.

Apart from oil or water content, what is also pertinent to take into account is the placement of plants in the garden and how they’re grouped. Plants that have a higher propensity for accumulating dead branches and leaves within the centre of the plant are considered high risk and should not be placed together.

Plants that are relatively open, loosely branched and have longer internode spacing between the leaves may catch alight quicker than compact plants because more air is circulating through and around them. However, because there is usually less dead plant material within these open plants, the assumption could be made that they are somewhat safer.

Trees with bark that sheds in ribbons are more of a fire risk than trees with smooth bark (although often it’s not as simple as this – for example, some eucalypts have smooth bark near the base but shedding bark in the higher branches). However, smooth-barked trees may not regenerate as quickly as trees with shedding bark, and they may not regrow at all.

On our website you will find tables based on the plant list from the brochure Fire retardant garden plants for the urban fringe and rural areas assembled by the Tasmania Fire Service. They include a range of popular native species for gardens that, if you live in a bushfire-prone area, should not be planted near your house (highly flammable plants), should only be planted on a small scale (moderately flammable plants) or are relatively safe to plant close to your house (slightly flammable plants). Find tables here.

Maintenance

Reduce fuel loads on your property by removing fallen branches (unless they are required for habitat) and leaf litter (if not overly detrimental to the ecological balance) as soon as possible. During bushfire season, keep all dead plant material clear of the house safety zone. Maintain the health of your plants to prevent them becoming a fire hazard and also to give them every chance of surviving a bushfire.

Images above and ‘Plant considerations’ text reproduced with minor adaptations from The Waterwise Australian Native Garden by Angus Stewart and AB Bishop, Murdoch Books, RRP $39.99. Read our review of the book in Sanctuary 50.

Caution: While appropriate garden design can have an impact on a property’s chance of surviving a bushfire, it is just one component of a complete bushfire survival plan and does not guarantee your own or your home’s survival in case of fire. The advice in this article is general in nature and should be applied with due consideration of your own circumstances.

further reading

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

In praise of Accoya

Native hardwoods are beautiful, strong and durable, but we need to wean ourselves off destructive forestry practices. Building designer and recreational woodworker Dick Clarke takes one hardwood alternative for a test run.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Airy flair

A minimalist renovation to their 1970s Queenslander unlocked natural ventilation, energy efficiency and more useable space for this Cairns family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Pretty in pink

This subtropical home challenges the status quo – and not just with its colour scheme.

Read more