Stay warm this winter with efficient heating

Heating can be responsible for a large proportion of a home’s energy use, but can make all the difference when it comes to winter comfort. We investigate the quality and costs of some efficient options, including hydronic heating systems and reverse-cycle air conditioners.

No matter how well designed your house is for passive thermal performance, in most of Australia and New Zealand you will probably need some added winter heating. But what heating system is best and most energy efficient for your home?

Although there are countless versions of gas-and electric-fuelled space heaters on the market, we are looking at two of the more efficient choices that you could consider: hydronic heating which uses radiators and in-slab immersed piping; and reverse-cycle refrigerated air conditioning, a form of heat pump technology.

Hydronic heating

Hydronic radiator systems consist of a heat source (boiler), one or more pipe circuits with heated water flowing through them, and radiators to emit warmth into the room. Some more complex hydronic systems have multiple zones, so you can choose to heat only part of the house, reducing energy use.

These systems have a number of advantages over other forms of heating. Hydronic systems emit heat either underfoot or close to floor level, which gives the feeling of warmth with lower ambient room temperatures than with space heating. This is because emitting heat at a lower level without the need for forced air movement (fans), the radiant convectors (radiators) avoid the cooling effect of airflows produced by heating such as reverse-cycle air conditioners or ducted gas furnace systems. Hydronic systems are also flexible: some boilers provide domestic hot water, eliminating the need for a separate water heater.

Disadvantages of hydronic systems include the initial installation cost. A complete system can easily cost $10,000 or more, depending on the boiler, the number of circuits and type of radiator. However, prices have dropped over time as hydronic heating becomes more popular and recent technology in boilers and pipe systems make it more affordable.

For a new build, and with a concrete slab floor, in-slab immersed hydronic floor coils can be laid with multiple circuits to provide perhaps the ultimate in comfort and operating costs, but you need to carefully consider the way these systems are controlled and insulated, to overcome potential heat lag from the heat bank in the floor mass. A system using wall or skirting radiators allows you to turn the heating on and off at will, and get heat within a minute or so.

Which fuel?

There are a range of options. Reticulated natural gas enables a gas-fired boiler to be used, but alternatives are solid fuels such as timber and manufactured pellets, solar energy, ground-sourced heat pump and air-to-water heat pump technology. Electric (non-heat pump) boilers and LPG-fuelled systems probably should be avoided unless there is no other choice available.

Solar systems have roof-mounted collectors that provide a proportion of the water heating, with instantaneous gas, heat pump or solid fuel heat sources used as a backup. Bear in mind though, heating is required at times of the year where there is the least solar input, and the water storage capacity required can be large, up to 1000 litres or more.

Heat pumps use a refrigeration system to extract heat from the outside air (or the ground or a body of water such as a dam) and concentrate it into the water tank. Even air that feels cold to us can contain a lot of usable heat, although the colder the ambient air, the lower the overall available heat capacity.

If no other fuel source is available or you have a low-cost source of solid fuel, such as fallen timber on a large property, solid fuel boilers can also be used to provide hydronic heating.

Arguably, the most greenhouse-friendly and lowest cost to run system would be a high-efficiency heat pump combined with a suitably sized photovoltaic array, although these systems are rare.

Reverse-cycle air conditioning

An energy-efficient heating alternative to a hydronic system is the room-mounted or central ducted system reverse-cycle air conditioner, also known as a heat pump. These systems use refrigeration principles and a reversing valve to heat (or cool) the air in your home. Unlike relatively inefficient resistive electric heaters that turn energy from one form (electricity) into another (heat), reverse-cycle systems use electrically powered compressors to move heat from one place to another; they use a lot less energy to produce the same amount of heat.

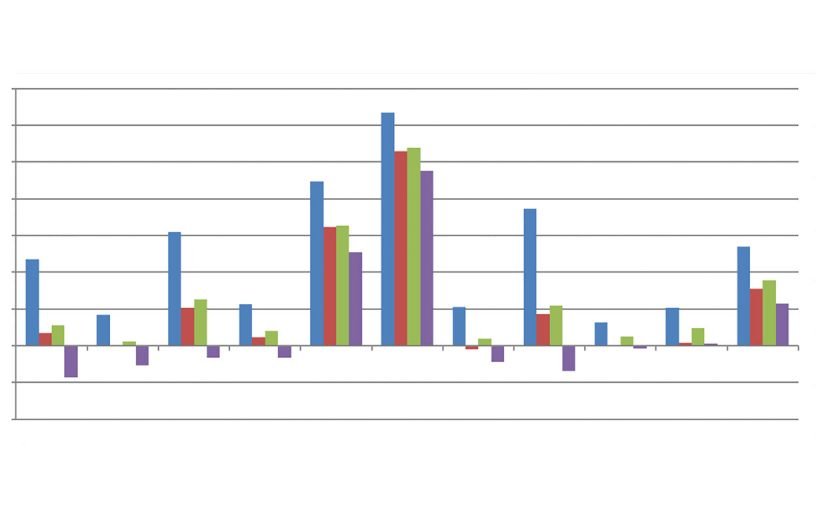

The efficiency of reverse-cycle systems is given by a coefficient of performance (COP). This is a ratio of the heat moved to the electrical energy input. As an example, if your heat pump uses 1kWh of electricity to move 4kWh of heat from outdoors to inside your home, then it has a COP of 4. The actual running COP depends on numerous factors, including the temperature differential between outdoors and indoors, the refrigerant and compressor type used, and overall system design.

These days, reverse-cycle air conditioners are mainly individual room or ‘split systems’; the indoor air-handling unit and outdoor compressor unit are separated and linked by high-pressure hoses. The split system has several advantageous features—the air handling unit is quite compact, they only need a couple of small holes in the wall, floor or roof for piping and cabling, and the compressor is outside.

What’s cheaper, hydronic or reverse-cycle?

It can be difficult to compare the two approaches. A single efficient reverse-cycle air conditioner will certainly be cheaper to run than a whole-of-house hydronic system. Even if you install several reverse-cycle air conditioners to allow you to heat the whole house, you are probably unlikely to run them all at once, and so your running costs may also be lower. However, a well-zoned hydronic system can be cost effective.

One advantage of reverse-cycle air conditioning is that you can start small, by installing a single unit, and then add more as the budget allows. With a hydronic system you really need to buy a boiler and ancillary equipment sized to suit the entire heating requirements of the home. With a reverse-cycle air conditioner, you also get cooling without having to buy a separate system. However, a whole-of-home reverse-cycle air conditioning system purchased just for its heating ability will cost more than a whole-of-house hydronic system.

Running costs will depend on many factors including the size of the system and its efficiency, so be sure to consider the size of the system and look at the efficiency data, whether for a hydronic system or a reverse-cycle air conditioner. For a given level of heat loss in a home, a system with higher COP will use less energy to maintain required temperatures.

A primary factor determining running costs is the thermal efficiency of the house. Remember, the better insulated the home, the less energy needed to heat and cool it, and the smaller, and therefore cheaper, the heating system you need to install. This means that you need to take all the usual efficiency measures, such as insulating ceilings and walls (and under floors if possible), sealing draughts, and insulating windows with either double glazing, curtains and pelmets, or both. In short, spend some money on energy efficiency measures up front and you will save on heating in both the long and short term.

Comfort and other considerations

Many other factors come into operating costs. Forced air systems of all descriptions do tend to dry the air within the conditioned space, which has a cooling effect of approximately three degrees Celsius, as you lose perspiration off your skin to your surrounds. This happens to a lesser extent with hydronic heating. As discussed earlier, hydronic systems tend to feel much more comfortable at lower temperatures than reverse-cycle air conditioners, as the radiant heat is at floor level and there is no cooling effect from air movement or reduction in relative humidity.

With heat pump hydronics, you might be able to access a cheaper off-peak tariff to heat the water, at least for part of the day. This will depend on your system’s design and your energy company’s tariff usage requirements. There are also opportunities to source electricity from renewable sources, rather than coal-fired power. If you have excess photovoltaic-generated electricity, you could use this to offset some of the running costs for heat-pump hydronic systems and reverse-cycle air conditioners. It’s important to note, though, that heating systems are most needed in winter when there are lower solar radiation (insolation) levels. An oversized solar system can help to some extent, but the savings are likely to be small. A battery could power the system at night, but currently the bill savings won’t offset the battery cost.

As for gas-fuelled systems, given that gas prices are now tied to international prices, the future costs of running a gas boiler can be difficult to predict. There’s also the issue that natural gas is non- renewable and becoming dirtier as more is sourced from fracking and coal seams.

Each home’s situation is different, so you need to evaluate the economics of the systems, based on your own particular circumstances.

Further reading

Buyers guides

Buyers guides

Beat the winter chills: A guide to electric heating options

As we head into the colder months, thoughts turn to staying warm. What’s the best electric heating system for you?

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Comfortably ahead: A tale of two heaters

Turn on your air conditioner—and knock hundreds of dollars off your heating bill. Tim Forcey describes the learnings (and savings) gained from his experiment with reverse-cycle electric heating.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Gas versus electricity: Your hip pocket guide

The results of ATA’s latest study on the economics of switching to electricity from gas for heating, hot water and cooking, for both solar and non-solar homes.

Read more Heating

Heating

Heating case study: converting gas to heat pump hydronic

This 1908 weatherboard Edwardian in Melbourne has been renovated, extended and insulated — and is making the switch to all-electric, powered by solar PV and 100% GreenPower.

Read more