On the drawing board: Passive House meets multi-residential

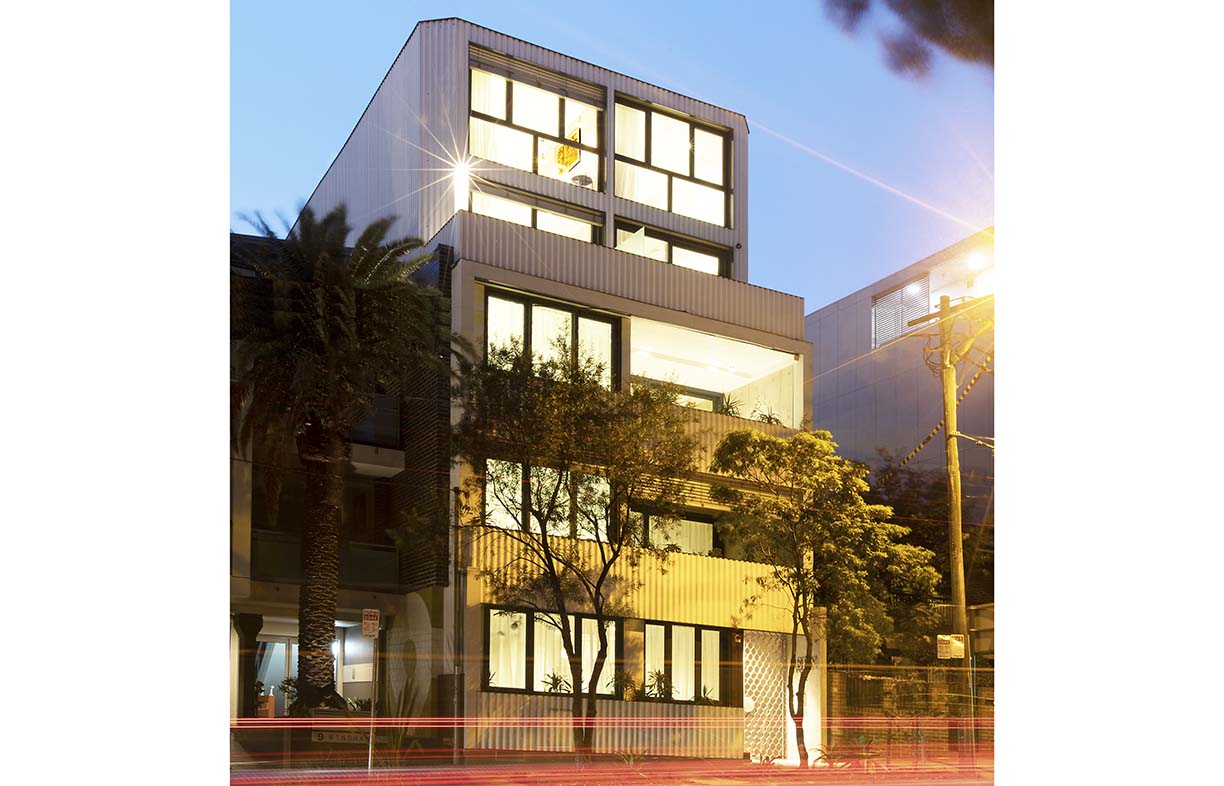

The Fern serviced apartments in Sydney’s Redfern are the first Passive House-certified apartments in the southern hemisphere. Architect Oliver Steele explains why he chose this approach for the project, the challenges they faced and what they learned about the potential of Passive House principles for delivering more sustainable multi-residential buildings.

Designing, building and developing the Fern took me and my team at Steele Associates years of research, design, innovation and problem solving. Our purpose was to prove that well-considered, sustainable design is viable in the competitive world of apartment development, share the learning, and encourage others to take sustainability seriously in the multi-residential building industry.

As Sanctuary readers may know, Passive House is a scientific approach to building that focuses on five key strategies to reduce energy consumption and improve the quality of the internal environment: eliminating thermal bridges, airtightness, high-performance glazing, super insulation, and mechanical ventilation with heat recovery. (You can find a more in-depth explanation at passivehouseaustralia.org; see also ‘Mind the gaps: Passive House from the inside’ in Sanctuary 45.)

Usually associated with single dwellings, Passive House is just as relevant to apartments. There are even some greater efficiencies for Passive House apartments compared to houses, such as grouping a number of dwellings into a single thermal envelope, which lowers costs. Stringent apartment fire-rating requirements that minimise smoke and heat transfer in a fire also help to achieve the airtightness required for Passive House.

Getting started

After the success of our first development project, three sustainable terrace houses in Newtown (see 88angel.com.au), I decided to bring our eco-development goals to high density living and embarked on designing and building 11 one-bedroom apartments 300 metres from Redfern station in Sydney’s inner south. We originally tendered to build conventional apartments on the site, but the developer decided he wanted out and asked me if I’d like to buy the land. This was an unexpected opportunity that I grasped with both hands.

Along with the vibrant buzz of this rapidly gentrifying part of inner Sydney, the site comes with the inevitable noise, dust and pollution of a modern metropolis. The front and rear boundaries are to the east and west, so I knew sun control would also be a challenge.

Parking wasn’t viable on our tiny 241-square-metre site, so 14 bicycle spaces are provided in the basement. There are five single-level apartments, two dual-level garden apartments, and four dual-level penthouses, all one-bedroom and ranging in size from 54 to 66 square metres.

When we submitted our new development application, I was still only vaguely aware of the Passive House standard. The Fern was originally designed to be a passive solar eco-development. However, the orientation was troubling me. The north facade was on the boundary, and had to be a blank fire-rated wall; there was limited opportunity for winter solar gain, which is critical to passive solar design. All our natural light was coming from the east and west, so we needed large areas of glazing on these facades. The problem with that is the summer morning and afternoon sun which beats in close to horizontally from these directions. How were we going to cope with these challenging conditions?

Through my research, I found more and more roads leading to Passive House, and started exploring in detail what it was all about. The scientific rigour of the standard intrigued me. Being established by a building physicist, the methodology is firmly founded in empirical science, supported by post-occupancy results. This was a refreshing approach compared to some supposedly ‘sustainable’ houses I’d seen that were actually thermally uncomfortable, power-hungry monsters in green skivvies.

I learned that Passive House uses passive solar design, and overcomes its limitations (particularly usefully on sites like ours that don’t have ideal orientation) by creating habitable space that can be effectively and efficiently decoupled from the ambient environment. So, when it’s too hot, too cold, too noisy or too dusty outside, a Passive House can enclose its occupants in fresh, clean, quiet comfort.

It’s important to clarify that Passive House gives you the choice to close off the outside world. You can still throw open the windows and doors for indoor-outdoor living, barbecues on the balcony, and breezes through your home when the weather is good. It’s up to the occupants to choose when to close the space to form their naturally lit, carefully ventilated cocoon.

At this time, my family was living in a three-year-old apartment building nearby in Redfern, where the wind whistled around doors and windows even when closed. The summer sun beat on the single-glazed doors, turning them into a massive panel heater in the living space in the middle of summer. I was shocked to wake up on cold winter mornings to condensation dripping off the inside of the bedroom window and pooling on the sill. Black mould started to form around the window frame during our time there: the result of ill-considered thermal envelopes and dew-point management. I needed no more convincing that Passive House was the way of the future.

It looked like we had the answer to the Fern’s challenging orientation, and had stumbled upon a solution to the noise, pollution and so on that the vibrant inner-city location brings. I made the call to commit to the Passive House system just six months before construction began.

So, what did we have to do differently to achieve Passive House certification and the benefits that it brings to the quality of internal space?

Thermal breaks

One of the most important innovations at the Fern was the structural thermal breaks we designed and built – the first in Sydney, we believe – to eliminate the thermal bridges that can cause problems regulating the internal temperature in conventional apartments.

When structural elements like concrete walls and floors continue from inside to outside – from the living room to the balcony, for example – they become conduits for heat flow outside in winter and inside in summer. Commercially available thermal breaks are expensive and oversized for Sydney’s climate, so we designed a solution for our concrete walls and slabs for around a third of the price. A thermal break consisting of 30 millimetre thick XPS foam insulation stiffened with fibre cement sheets separates internal and external sections of concrete; reinforcing rods terminate either side of the break, with partially rubber-covered stainless steel dowel connectors passing through the break. This assembly thermally decouples the inside and outside structures, while carrying the structural loads uninterrupted.

Airtightness

Australia’s homes have a problem with airtightness – they’re draughty as heck. A CSIRO study found the average Sydney home has an air infiltration rate of 20.8 air changes per hour (ACH) when tested at a pressure of 50 pascals; they are “poorly sealed and have higher levels of air leakage than would be expected of newly constructed houses.” Although our building code notes that houses should be reasonably well sealed, airtightness isn’t generally tested and even many newly built homes leak air like sieves.

One of the keys to the effectiveness of Passive House design is the stringent airtightness requirement. During construction, we undertook thorough blower-door testing, pressurising and depressurising each apartment to test for and eliminate air leakage. The fire-rated construction mandated for multi-residential buildings helped in this regard, because it isolates apartments fairly well if done properly. We used a combination of specialist tapes, sealants and expanding foam to close any remaining gaps. This was a time-intensive process, and the hardest part of the Passive House standard to achieve. But the results are in, and the Fern’s infiltration rate is between 0.3 and 0.5 ACH, below the 0.6 ACH upper limit for certification for every apartment. That’s about 40 times better than the Sydney average. Draughts begone.

The benefits of an airtight building envelope include improved thermal comfort, reduced noise, reduced dust and allergens, and superior control over ventilation.

Doors, windows and shading

Another first for the Fern among Sydney apartments is triple glazing. This keeps the inside cosy in winter, and the low-e coating helps keep the sun’s heat out in summer. Door and window frames are timber for thermal resistance and aesthetics inside, with aluminium external cladding for durability. Lift-and-slide doors and tilt-and-turn windows provide air sealing and acoustic barriers. The glazing has an average U-value of 1.38 and solar heat gain coefficient (SHGC) of 0.33. To put that into perspective, NatHERS compliance levels were U-value 6.7 and SHGC 0.7, making our glazing nearly five times more energy efficient than a merely code-compliant solution.

Adjustable horizontal blade blinds on the exterior of the Fern are equipped with timers and light sensors to ensure that the glazing is further protected from summer morning and afternoon sun, but lets the warming sunlight through during winter.

Super insulation

Insulation at the Fern is roughly double that typically used in Sydney apartments, and is installed as a continuous barrier to eliminate thermal bridges and act as a blanket to cocoon the living spaces. The roof is insulated to R7.0, walls R3.5, and floors R1.5.

The careful planning and detailing of our thermal envelopes mean that the thermal mass, in the form of concrete, is on the interior. This not only allows our exposed off-form (meaning the finish is produced by the formwork used to cast it) concrete walls to shine aesthetically, but may improve the thermal performance of the building. Interestingly, the Passive House system recommends against the use of thermal mass, on the basis that it makes the space less nimble in adapting to ambient temperature changes. Structural and fire requirements dictated the use of concrete for the Fern, though; we’ll see how it performs through post-occupancy testing over the coming year, so stay tuned.

Fresh air

Once you’ve created a naturally lit, well-sealed cocoon for living in, you need fresh air for those times when you choose to isolate your space from the outside world. Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) systems at the Fern provide fresh air in each apartment, filtered to allergenic levels, at a comfortable temperature year-round: the heat exchanger at the heart of the system transfers heat between incoming and outgoing air without mixing the two. This process is 85 to 90 per cent efficient, and a good MVHR unit uses only 40 watts at full power.

The problem we faced was that Australian building codes wouldn’t allow MVHR to be used for bathroom exhaust. So together with the Australian Passive House Association and Fantech, we commissioned a study comparing an MVHR-ventilated bathroom to one ventilated with a code-compliant standard exhaust fan. The study proved that the Passive House MVHR solution was actually superior to the compliant one. The certifier accepted the Fern’s systems as an alternative solution under the code, so now this approach is available to all Australian homes.

Run on sun

Being net positive for energy was a primary goal at the Fern. We designed a custom support system to squeeze a 21-kilowatt solar PV array on the roof.

On completion in mid-2019, the Fern was sold and is currently being run as serviced apartments, allowing many people to have the Passive House experience. In the first three months of its operation, the Fern used 4,751 kilowatt-hours of electricity and we were thrilled to see that it generated 5,651 kilowatt-hours – 19 per cent more than it used. The second quarter also proved net-positive in electricity generation. There’s no gas in the building, so that means all appliances, hot water, heating and cooling, the lift – everything – runs on solar, with energy to spare.

The experience

Beyond the technical side of sustainability, at the Fern we aimed to create spaces that would be enjoyed and valued for years to come. Because ultimately, it’s the spaces people value that are retained in the long term. All but one apartment have generous balconies or gardens; the front and rear wings of the building are separated by an open atrium, and all common spaces are open to the sky.

The structure is all in-situ (poured on site, as opposed to precast) concrete, often exposed, and juxtaposed with warm, detailed timber finishes. Countless hours went into the detailing of joinery, bathroom layouts, kitchen functionality and material selections to create warmly textured, well-considered spaces. The concrete walls were hand-buffed with natural carnauba wax to imbue a soft sheen: a labour of love over three months.

Guest feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. The two 15-metre-high green walls in the atrium signify to visitors that they’ve arrived in an oasis that feels a million miles from the dust and grit of the city, and yet is on its doorstep. People are amazed how quiet the apartments are. The balcony door feels like an airlock as it closes with a solid ‘thunk’, and the apartments stayed cool during heatwaves over the past summer.

Passive House for the future

My next challenge is to bring Passive House principles to affordable housing: to apply all we’ve learned at the Fern more efficiently with economies of scale. We’re now exploring key-worker accommodation (for people who provide essential services on average or below average incomes) and aiming to create simple, compact, economical homes that are luxurious by virtue of the clean, fresh, quiet sanctuary they provide in the midst of the bustling city.

There’s no reason all Sydney apartments built in 2020 and beyond can’t incorporate Passive House principles and be net-energy-positive. No reason except the powerful inertia of a conservative industry, hesitant government, and a poorly educated market. So how do we overcome this triumvirate of challenges?

Don’t wait for government. Although there is progress being made on raising minimum standards for energy efficiency, it’s at a glacial pace.

Don’t wait for industry to lead. Developers are understandably risk averse, and respond to the idea of Passive House with the questions: is it a risk? Is there profit in it? I’m hopeful that the successful completion and sale of the Fern and our willingness to share the learnings will encourage at least a few developers to take sustainability seriously. But without pressing market demand, I’m not holding my breath.

The quickest way we can increase the sustainability of apartments is through consumer demand. If home buyers want the benefits of Passive House, demand it, and are willing to pay for it, industry will provide it. Just look at appliances: developers regularly install expensive European appliances because that’s what the market demands and will pay a premium for.

Can you imagine the power of a market that demanded and paid a premium for net-energy-positive living? And you’d pay off that premium in substantial utility bill savings over time. I’d like to see a European appliance as smart as that.

further reading

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

In praise of Accoya

Native hardwoods are beautiful, strong and durable, but we need to wean ourselves off destructive forestry practices. Building designer and recreational woodworker Dick Clarke takes one hardwood alternative for a test run.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Airy flair

A minimalist renovation to their 1970s Queenslander unlocked natural ventilation, energy efficiency and more useable space for this Cairns family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Pretty in pink

This subtropical home challenges the status quo – and not just with its colour scheme.

Read more