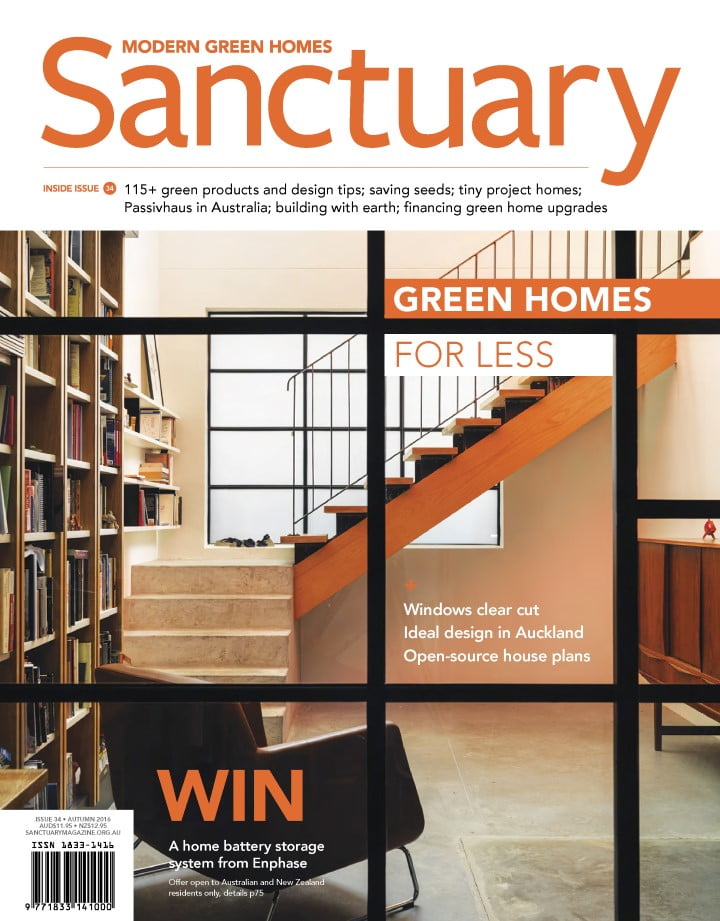

Over to you: Open source housing

Off-the-shelf housing is for many a rare chance at home ownership – which, though out of the reach of many, is still highly prized in Australia. We look at some innovative takes on the project home that aim to shift the power from the developer to you. Plus, is sustainability finally finding a foothold in the mass market project home space?

Marcela and Rob eye the neatly stacked piles of timber on the bare earth and ponder the detailed instruction manual. The collections of uniformly sized shapes wait idle for the exact configuration which will bring them to life. These beams and hooks will not become a bed, or even a kitchen, but their new house.

The above scenario, while fictional, might not be as unlikely as it sounds, if a global scheme to bring high quality design to the people takes off. WikiHouse is an open-source building platform that promises a fully constructed house in as little as a week, without the use of skilled labour or anything more than basic tools. The freely available architectural plans can be applied digitally to a computer controlled material cutter (CNC machine) to create precisely measured materials from locally sourced, standard products such as ply.

New Zealand WikiHouse chapter co-founder, British expat Martin Luff, was motivated by disaster. Living in Christchurch when the city was struck by a series of catastrophic earthquakes in 2010 and 2011 – and which continue to hold parts of the small city in varying states of limbo – he decided to contribute to the rebuild effort. He would turn his product and digital design expertise to houses, with the idea of creating a blueprint for a better kind of building.

“A lot of the houses that were being built pre-earthquake were poor quality, unaffordable and just substandard, and I thought they shouldn’t be,” Martin says. “I had the skills and therefore in a way I felt obliged – we are in the top one per cent in terms of education and opportunities compared to those less fortunate – and I thought, no one else is having a go, so I should.”

Martin teamed up with fellow designer Danny Squires and together they formed Space Craft Systems, the New Zealand arm of the UK-based and now global WikiHouse movement. The start-up is now working to take its small proof of concept structure through to a fully finished demonstration house.

The demonstration house aspires to Passive House standards; with carefully controlled ventilation, high levels of insulation and low-embodied-energy materials, but the commitment to sustainability is broader than the design itself, Martin explains.“We wanted to go beyond sustainability and to think about restorative systems – looking at all aspects,” he says. “So in terms of economics, for it to be self-sustaining, for it to happen on a sustainable scale, and of course environmental sustainability.” In the long term they plan to adopt a comprehensive framework such as the Living Building Challenge to measure their success, with a set of monitoring systems to be built into the design and post-occupancy evaluations to help refine the process.

Standardising place?

While sustainable design experts are generally in favour of anything that normalises green building, some have concerns about the open- source movement. Melbourne University ESD expert Dr Dominique Hes sees a danger in passing on the building of houses to non professionals. “Many of the crucial elements of sustainable design could be lost,” she says.

Dominique sees more potential in the prefabricated housing model, which has been in practice in Japan for many years and is now gaining traction locally. In such projects, “there is a database of 50,000 home components, tied to a manufacturing base, the designer sits down with the client and designs their home with them using these components and the site,” she says. “The result is an efficient, prefabricated, customised home that is quick to build.”

She also cites the work of Castlemaine-based architect Geoff Crosby who is developing an apartment complex, also to the stringent Living Building Challenge standards, as a good model for replication (see more on the Living Building Challenge and prefab housing in Sanctuary 31). Dominique is acting as an advisor to his projects, and says they led what will be the first ecological survey of a pre- developed site with the aim of “healing and contributing to local ecology” during the build.

Geoff suggests that while open-source design could work well in some contexts, he is wary of a stock standard approach. While some aspects such as the right orientation could be easily controlled, he says it is hard to standardise character and site-appropriate attention to a building’s environmental impact. “Architecture isn’t like product design, it is integral to place – architects should act as mediators between people and their location to get the best outcome.”

He agrees there is a need to make comfortable and well designed homes accessible to more people, but suggests that rather than offering off-the-shelf solutions, experts in the field should think more about knowledge sharing.

Your Home open-source plans

One of the most significant boosts to open-source housing design in Australia has come courtesy of the federal government. Your Home, part of the Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, released the first of its free high-performing house plans in September 2015, and report they have attracted a “huge amount of interest.”

The one-storey design is available as three or four bedrooms, as part of its Design for Place initiative. Spokesperson Bronwyn Pollock says that the plans need to be adapted by a draughtsperson to meet the needs of the local council, allowing the application of understanding of local conditions. The plans come with modifiable specifications for each capital city and seven design principles including orientation, shading, ventilation and natural light. Bronwyn says the program aims to make sustainable design accessible to those who don’t have access to an architect or designer, and to demonstrate that a comfortable, energy-efficient house needn’t cost more.

“The tendency in current building is to maximise size over functionality. The designs are intended to show how a well-planned design can be adaptable and serve the different needs of your household over time, while still being energy-efficient.”

She says a number of owners have made Your Home aware of their intended use of the scheme, with several revised plans currently sitting with various councils for approval.

Prefab NZ also sees promise in the open-source future and is running a design competition to produce an open-source ‘bathroom pod’, which could be added in a variety of contexts anywhere in the world.

While open-source house plans may not have caused the revolution some have anticipated, it’s hard to deny a shift in the accessibility of architecture. The potential for shelter to be created to a guaranteed standard without project-length expertise means that we could be closer to (at least one version of) the project home of the future.

In focus

In focus

Inside the war on construction waste

Deconstructing buildings to salvage materials is less common than demolition for landfill – but could this be about to change?

Read more In focus

In focus

Lessons learnt

Five years ago we featured a house in the Currumbin Ecovillage on the Gold Coast that was designed using three pavilions to accommodate two households in a co-housing arrangement. How is their experiment evolving? We revisit to find out.

Read more In focus

In focus

Get the most from your solar PV for summer cooling

Cooling your house using your rooftop solar system requires a bit of thought and planning, but when you get it right, the savings can be well worth it.

Read more