The rise of the courtyard

As courtyards replace backyards as the primary outdoor space, architect Marie Carrel explains how they are best designed to maintain liveability.

Courtyards have become something of a buzzword in our suburbs as they constitute the secluded private open space that developers are generally required to provide when building units. They are essentially a reduced version of the backyard, but while they do not allow for cricket-playing, they are still the place to have a barbecue and let the kids grow some strawberries. These are welcome lifestyle ingredients in modern Australia where people like to eat outside and often love gardening, but have no time to maintain extensive gardens.

Nonetheless, many multi-unit developments have been designed with courtyards that are too small for lifestyle purposes and appear to be mere leftover ground between the house and the fence. They are token gestures designed to satisfy an accommodating municipality rather than provide thoughtfully-planned outdoor living space.

‘Courtyard houses’ vs ‘houses with courtyards’

There is an important distinction between a ‘courtyard house’ [see definition at end] and a courtyard more broadly, that small outdoor space tucked in next to or behind a house, or provided as part of a multi-unit development.

Courtyard homes have been used throughout history in many cultures and represent a significant archetypal building form which is still useful today. In modern Australia, you might see a house built around the perimeter of an open space as a secure and protective structure affording privacy from neighbours. However, they are not an immediate choice for the average sized Australian block.

While there would be plenty of room for courtyard homes on acreage (where privacy is not an issue), suburban properties are rarely wide enough to accommodate building wings along each side boundary as well as a decent sized courtyard in the middle. Additionally, courtyard houses spread out the built form and create smaller outdoor spaces, as opposed to a more compact home that leaves a bigger backyard ready for playing cricket. As a result, they are better suited to adult entertainment than to children’s recreation. An L-shaped home with a solid brick wall on the unbuilt boundary might be an option to solve these issues, providing a happy hybrid space between courtyard and backyard.

When courtyards work best

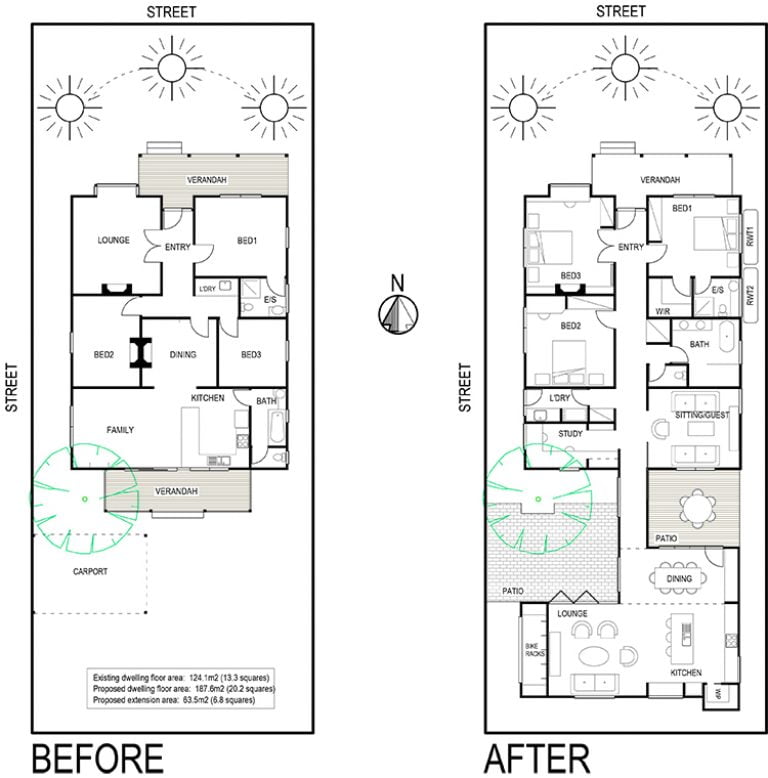

I use courtyards liberally in my practice, but almost solely in that particular situation where a property presents a south-facing backyard. We locate the sleeping zone at the front of the property and connect it to a living area pod at the rear with a courtyard or two in between. This allows both the front and the rear rooms to secure passive solar access while offering privacy to the living areas. It’s an effective design strategy which leaves either no backyard behind the rear pod or a small one, depending on property size and owners’ wishes.

Houses that face other directions may also benefit from courtyard spaces. For example, where a long external wall faces either east or west, it can be indented with a courtyard to provide north-facing windows to some adjacent rooms. The land pocket hence created can also be pleasantly landscaped to provide a small garden view or a petite deck. This is in fact a charming way to introduce additional private open space and different aspects from the house.

Getting the size right

We find in our practice that minimum dimensions of 5m x 8m and adequate landscaping go a long way towards providing a pleasant courtyard space. A 5m width allows for proper setback of the facade from the fence, which when the courtyard is on the north ensures adequate passive solar access is retained even when the house next door goes up another floor. This dimension effectively allows for a 3.5-metre-wide patio or deck suitable for dining and a 1.5-metre-wide garden bed along the fence, which is adequate for planting small deciduous trees and providing a green view from inside. The 8 metre length accounts for a 4-metre-long deck or patio (this will end up a 3.5m x 4m area) and another 4-metre-long patch that can be turfed or dedicated to growing vegetables.

Pitfalls for sustainable design

Courtyard houses can also be problematic for a low energy home as you may end up with more rooms than you wish for that face east, south or the dreaded west. As well as being space-hungry, they also require more external walls, resulting in higher building costs and greater energy loss than rooms huddling together in a compact house. So, while courtyard houses might be attractive as they offer seclusion and a generally well-considered outdoor space, they do not suit all properties and are generally not designed with environmental sustainability highest on the agenda.

Courtyards and the future of backyards

The beloved Australian backyard is under siege and two powerful forces are turning it into a fast-disappearing act in most residential streets. The first is commercial reality as developers know that building two or three homes onto a single house block is a profitable enterprise in a hot real estate market.

The second is that there is now substantial demand for smaller quarters. In part, it comes from residents culturally used to living closer to each other and who may even prefer it that way. But there is no denying that a younger generation of Australians, the ones raised in the iconic Australian backyard, are now relinquishing it too. Indeed, what to do when that green patch you can afford for your children is an hour and a half away from the city centre you still want quick access to? This can raise questions in some people’s minds about the next generation of children being raised in a courtyard, or worse, on a balcony!

I have no such fears personally, my brother and I having been raised in an eighth-floor apartment in central Lyon, France. But while the garden-loving Australian culture may object to most kids being raised in these conditions, it is certainly evolving to accept smaller outdoor spaces and appreciate low-maintenance requirements. This is not to say that a courtyard of any design or size can successfully replace a backyard. I note with concern that many authorities and developers have been quick to adopt minimum requirements that are falling well short of providing an adequate and pleasant outdoor space.

Where the unit courtyard is designed as a meaningful space rather than an afterthought, it will be well used and cared for. Such a setting encourages occupiers to look at units and townhouses as a sustainable place to live rather than as temporary or compromised accommodation – and they get to enjoy the pleasures of an outdoor space while staying close to the city centre. There is no doubt that where town planning authorities defend adequate courtyard dimensions, the dwindling of the backyard can contribute to the sustainability of our ever-densifying cities. This while helping to moderate our fear of raising kids in a concrete jungle.

Courtyard houses

The courtyard house is an archetypal building form that is still useful today. As well as offering privacy and protection, courtyard homes have also been used to provide shelter from fierce winds in extreme climates as well as natural ventilation in hot or tropical areas.

The original courtyard houses date back to 6000BC and are thought to have developed from the need to let smoke escape through a hole in the roof of houses with a central fireplace. Over time, the roof opening got bigger and the courtyard house was born. Such dwelling types are common in India, Mexico, China and the Middle East. In China, several houses would be built for extended family members around a central compound to provide independent living as well as ready help and company. The Roman courtyard house is constructed around the central impluvium, a basin designed to collect water from the house roof.

On the drawing board

On the drawing board

On the drawing board: Hempcrete homestead

Nicola and Dan designed and built a hempcrete Passive House on a four-hectare homestead in Central Victoria, with an uncommon central sustainability feature: co-living.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Saving stormwater

You can do a lot around your house to prevent stormwater runoff, simply by opting for permeable surfaces when landscaping.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Doing things differently

Grappling with housing unaffordability, two Sydney friends pooled their resources – and tapped into family connections – to realise their home ownership goals.

Read more