On the drawing board: Of lovable, well-made things

Inaugurating our new series On the drawing board, architect Matt Elkan muses about beauty and quality in the built environment, how they contribute to longevity, and how an appreciation of both has informed his recent work.

After nearly fifteen years of running a small architectural practice focusing largely on low impact environmentally sustainable houses, I had a ‘penny drop’ moment last year that has had me reconsidering the value of beauty and quality in the built environment.

For most architects, beautiful things are a bit of an addiction. We love to surround ourselves with them. We like to think we can help to create them. But deep down I’ve always had a nagging suspicion that maybe beauty is just a whimsical thing of no real lasting value. Certainly it has been hard to link beauty and sustainability in my mind. You could have one or the other, or perhaps sometimes both. But I had never come to any firm conclusions about how intrinsically linked they are. Until recently.

In the past nine years our practice has designed five rear additions to old houses in Sydney. Each project involved an original house of somewhere around 100 years old, with a rear extension added in the 1970s or 1980s, and in all five cases we were engaged to remove the recent addition and design a new one of (hopefully) much higher quality and beauty in its place. The moment of realisation – that only dawned after tackling a number of these similar problems – was that at no point in the design process of any of these projects did anyone consider demolishing the old part of the house and keeping the late twentieth century part.

None of the clients were particularly sentimental about built heritage, and there was no overt philosophical discussion about conservation of old buildings. But it was so obvious that the old parts of the houses were things of quality and the additions were defective at a number of levels, that the idea of keeping the newer parts of the houses at the expense of the old would have been considered a bit crazy.

And this was the point that got me thinking. Beauty and quality are of value because we preserve the things we love. Forget heritage laws which mandate conservation. Think instead about the conservation we do because we want to, because it’s logical.

When viewed from the perspective of sustainability, preserving buildings longer means building less often, which in turn means less waste and less energy and material consumption. A lot of energy and resources go into the manufacture and transport of materials used to construct a home, yet eventually most of these materials end up in landfill: according to Your Home, around 42% of the solid waste generated in Australia is building waste. Research by CSIRO has found that the average house contains about 1,000GJ of energy embodied in the materials used in its construction. This number will obviously vary greatly according to the size and type of house, but amounts to a significant proportion of the total energy used in the house during its life.

As an indication, the average NSW household uses approximately 5550kWh (or approx 20GJ) of energy per year. So, the embodied energy in construction is equivalent to 50 years of normal operational energy use. To put it another way, if a house lasts less than 50 years, there was probably more energy used to build it than it used in its life. Using materials with less embodied energy and choosing materials that can be recycled or reused will obviously improve this equation. However, this must surely also push us toward long-term thinking in what we build and how we build. The longer a building lasts, the better the equation becomes.

And returning to the point, if a house is well built and loved, it is much more likely to be maintained and preserved. Below, I explain two recent projects in which the goal of building homes of beauty and quality led to different decisions about renovation.

Adding to quality: Navigator’s House

The Navigator’s House is a house for a family of sailors overlooking the upper reaches of Sydney’s North Harbour. The owners bought it for the position and for the beautifully built brick and sandstone cottage on the site. It is said to be the first house in the locality, which would make it well over 100 years old. Despite lime mortared brickwork, there had been no movement, cracking or leakage in the house’s history.

The argument against buying the house was a 1980s lean-to addition suspended above the ground on large brick piers. The addition was cold, dark and disconnected from the backyard. Windows were light gauge aluminium with 3mm glass, and leaked air badly. Neither the walls nor subfloor were insulated. The old part of the house had generous 3.2-metre ceilings; this compressed to under 2.4 metres in the 1980s living room extension. It was understood from the outset that if the house was to be a viable long-term home, the addition would need to go.

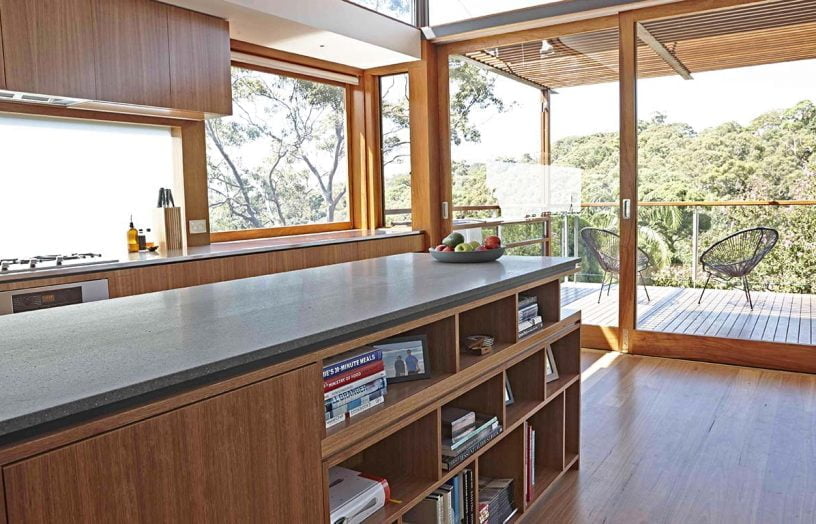

And so at the point when our office came to be involved, the brief was to construct something of equal gravitational pull to the old. Something new, and light. Something well insulated and connected to the landscape. Something that could complement what the old house offered.

It was an on-and-off design process that lasted almost 10 years, and saw the owners move from being interested spectators to committed participants in the design decisions: the house was shaped by the owners as much as by us or the builder, Cunningham Building Solutions. The new house benefits enormously from the existing brick and sandstone walls that were integrated into the new design. They ground the house and reinforce the sense of permanence. In contrast, lightweight modern structural members allow for the possibility of much larger operable windows, doors and screens in the new portion of the house. Much of the timber used was recycled from the old extension, and all new brickwork uses bricks salvaged from elsewhere.

The old house has a particular quality, as does the new extension. And it is our hope that they sit alongside each other now as equals, neither half subordinate to the other.

Subtracting to get quality: Fraser Tran House

In the rapidly densifying North Shore suburb of Chatswood, Sydney, these homeowners were after a house which engaged with natural light, fresh air and outlook while providing a sanctuary from the external world. Their project, initially a renovation, illustrates another related moral dilemma: at what point do we decide an old house is ‘irredeemable’ and consign it to demolition for the sake of a high-quality new house?

The existing house was a postwar parapet-roofed brick cottage. It had a certain style about it that was attractive and the owner, who had originally trained as an architect, initially sought to renovate and improve it. Our office was engaged at about the point where the owner had reluctantly decided that a new house was necessary. The issues with the house were numerous and mainly related to the poor quality of the existing structure. The parapet roof trapped leaves and, as a result of leaf and moisture buildup, it was rusted, leaky and needed replacement. Moisture had found its way through the brickwork and damaged the internal and external finishes. The basement was uninhabitable due to mould and damp issues. In addition, the layout of the house was so complicated and haphazard that it would have required numerous structural modifications to rationalise light and circulation.

The new house, built by Harding and Lindsay, is bigger but simpler. The orientation is to the north, with big windows and overhangs in this direction. Circulation is clear and linear. Materials are deliberate and natural. The roof is large and sheltering. Spaces are open and flexible with the aim of allowing versatility over time. Windows and doors are all recycled hardwood from old houses around the Wollongong area. It was a difficult decision to demolish the old house, but the hope is that the new house is of such quality and beauty that it will be loved and preserved in its turn for many decades.

Touching the earth deliberately

Iconic Australian architect Glenn Murcutt’s maxim of ‘touching the earth lightly’ comes as easily to me as breathing, thanks to my training as an architect in Sydney in the 1990s. The idea has a certain resonance and reminds us of our custodial duty to the Earth. However, ‘lightly’ does not mean building impermanently, or without sufficient thought.

Speaking recently to Guardian Australia, Murcutt said: “Touching the land lightly is not about a building with just four columns. It’s about: where did that material come from? What damage has been done to the land in the excavation of that material? How will it be returned to the earth eventually, or can it be reused, can it be recycled, can it be put together in a way that can be pulled apart and changed and reused?”

Perhaps we could also add touching the earth ‘deliberately’. Let’s not kid ourselves that building is without impact. But it’s important to have a clear picture of what we are doing and to do things well. To design and build well is hard, but it’s good work. In thinking things out, planning carefully, consulting at length and building with pride and care, we leave behind artefacts that stand a good chance of being loved and preserved. Human effort is the most renewable resource we’ve got.

Further reading:

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

In praise of Accoya

Native hardwoods are beautiful, strong and durable, but we need to wean ourselves off destructive forestry practices. Building designer and recreational woodworker Dick Clarke takes one hardwood alternative for a test run.

Read more Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

Energy efficiency front and centre: A renovation case study

Rather than starting again, this Melbourne couple opted for a comprehensive renovation of their well laid out but inefficient home, achieving huge energy savings and much improved comfort.

Read more