Modern green homes: A short history of energy-efficient housing in Australia

As we celebrate 50 issues of Sanctuary, it’s timely to look back at how far the ‘modern green homes’ of our tagline have come in the magazine’s lifetime. CSIRO building researcher Anthony Wright looks at the development of energy efficiency regulations, how we’re building, and where to next for achieving a truly sustainable built environment.

Climate responsive design is nothing new, but it does sometimes seem like it must be rediscovered over and over. About 2500 years ago Xenophon recorded Socrates describing “beautiful and good” houses in ways that, adjusting for his northern hemisphere perspective, will be familiar to Sanctuary readers:

“Now in houses with a south aspect, the sun’s rays penetrate into the porticoes in winter, but in summer the path of the sun is right over our heads and above the roof, so that there is shade. If, then, this is the best arrangement, we should build the south side loftier to get the winter sun and the north side lower to keep out the cold winds. To put it shortly, the house in which the owner can find a pleasant retreat at all seasons…”

At around the same time Aeschylus imagined the god Prometheus asserting that before he endowed them with reason, people were barbarians and “lacked knowledge of houses turned to face the winter sun, dwelling beneath the ground like swarming ants in sunless caves.” In the 15 years since Sanctuary magazine was first published, are we still building houses for barbarians?

Regulating energy-efficient housing: two steps forward, one step back

When Sanctuary was born in 2005, the government-published guide to sustainable building, Your Home Technical Manual, was only one year old and the 5-Star standard for new homes was still being introduced. The average new house rated 3.5 or 4 Stars, which was an improvement on the 1.5 to 2-Star average for all Australian houses.

Two years later, climate-minded voters helped to secure a pyrrhic victory for the Labor Party with Kevin Rudd’s election in 2007. Shortly thereafter, government stepped into action with plans and programs to support decarbonisation. Then came the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 and some of those plans were accelerated: the Energy Efficient Homes package and the Green Loans Scheme were rapidly implemented. The package saw the rollout of ceiling insulation installation across Australia and the rapid proliferation of house energy assessors. The tragic deaths arising from the insulation scheme and the collapse of the industry for home assessments did much to discredit all house energy efficiency programs, not to mention the government. Despite these events, the 2009 National Strategy on Energy Efficiency (NSEE, affectionately known as Nessy) included several proposed measures aimed at improving our residential housing stock. Among them were an increase in the stringency of energy efficiency provisions for all new residential buildings (to a 6-Star minimum); mandatory disclosure of residential building energy, greenhouse gas and water performance at the time of sale or lease; and incentives for energy efficiency improvements.

Ultimately, not even Nessy could save Kevin. By July 2010 Julia Gillard was Prime Minister and the NSEE delivered a 6-Star mandatory minimum for new housing, fully implemented by May 2011 – the standard we still have today.

The Gillard Labor government also introduced the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme in 2012 which introduced a price on carbon for the first (and to date, last) time.

In 2013, some years after the advent of the first mandatory minimum, the CSIRO published what is still Australia’s only large-scale analysis of minimum energy performance standards: ‘The Evaluation of the 5-Star Energy Efficiency Standard for Residential Buildings’. Among the study’s findings was that a 5-Star house in Melbourne consumed 50 per cent less gas in heating than a house built prior to the new standard. And most amazingly, the study found that houses built to the 5-Star standard actually cost about $7500 less to construct than those built to earlier standards, due primarily to a reduction in glazing area and a reduced surface-area-to-volume ratio. Although the study wasn’t large enough to be conclusive, it seemed that the case had been made for the efficacy of minimum standards.

Those opposed to the introduction of the 6-Star standard claimed it would raise housing prices. Land prices certainly increased dramatically but looking back, concerns about construction costs were not well-founded. New dwelling inflation fell well below its long-term average for two years, despite the cost of building materials increasing, before returning to around 3 per cent in 2012. New home buyers would not have noticed a jump in prices as a result of the introduction of the standard.

Buoyed by the success of NSEE and the introduction of a price on carbon, the government must have figured an even longer acronym would be even more successful and devised the National Draft Standard Setting Assessment and Rating Framework. The framework promised to improve minimum standards, align rating scales across commercial and residential buildings, harmonise tools and introduce disclosure of building performance at sale or lease. It was such a good idea it was bound to fail, and fail it did, with state after state abandoning the framework development process as elections toppled governments across the country, culminating in federal Labor’s replacement by Tony Abbott’s Coalition government in 2013. The Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme was also an early casualty of changing politics, repealed in 2014.

Housing policy was left with the 6-Star standard but not much policy guidance, until the National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP) was released in 2015. Among its 34 individual measures the NEPP includes ‘Advance the National Construction Code’, ‘Improve compliance with energy efficiency regulations’ and ‘Improve residential building energy ratings and disclosure’.

Addressing the first of these measures, last year saw COAG Energy Ministers agree on a Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings – a national plan that sets a trajectory towards net zero energy (and carbon) buildings for Australia. The first increase in stringency of the National Construction Code under the Trajectory is scheduled for May 2022 [Ed note: see Sanctuary 49 for more on Renew’s involvement in the campaign for this]. On compliance, we have seen improvements to tools, training and industry workshops. It is expected that the focus on building compliance in general, due to flammable cladding and structural failures, will improve in coming years. An ‘existing buildings’ addendum was added to the Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings very recently. Good ideas seem to bob to the surface every few years, and thanks to the Trajectory, disclosure of energy performance at sale or lease is one good idea that seems like it might be waving not drowning right now.

Building the houses

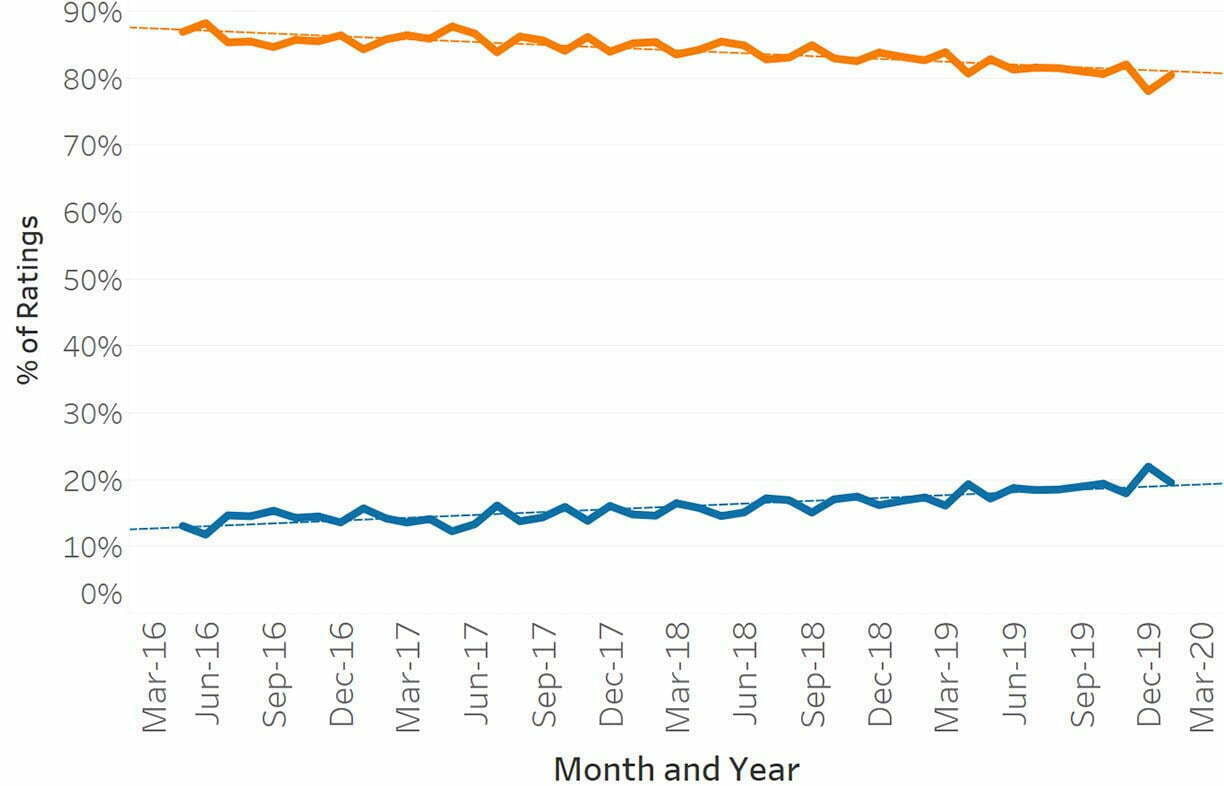

While the politicians and bureaucrats have been thus occupied, builders and homeowners have been busy getting on with the job. In 2016 CSIRO started to collect the NatHERS certificates generated to comply with the National Construction Code. The data has been illuminating. Slowly, as the benefits of building healthy, comfortable and efficient homes have become more embedded, people are voluntarily opting for houses with higher energy efficiency ratings. While most still design houses to the minimum standard, the number of dwellings rating more than 6.5 Stars has steadily increased across the country.

And slow national progress masks the fact that some states are going well beyond minimum standards. In Tasmania the number of buildings designed to more than 6.5 Stars will very soon outnumber those built to minimum standards. [Ed note: see ‘Are we aiming for the Stars?’ in Sanctuary 48 for more on this.]

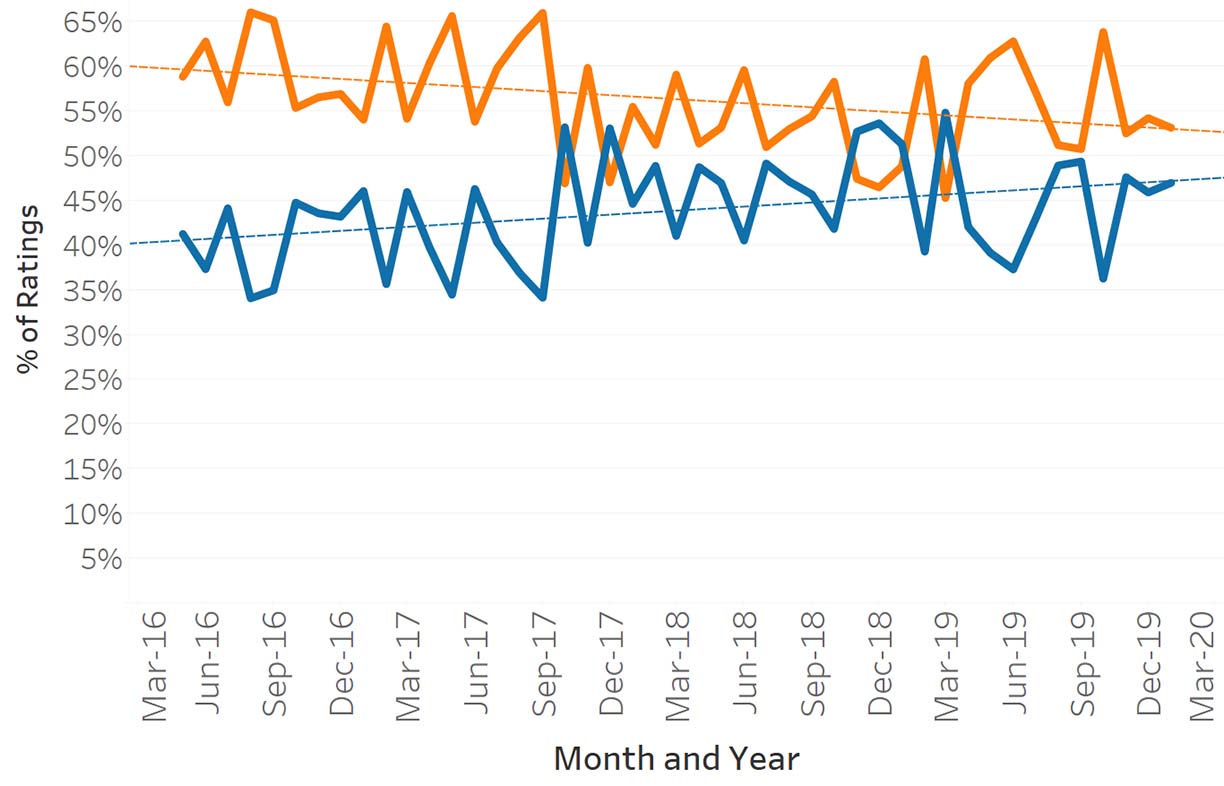

CSIRO’s database also allows us to see how designers and builders are meeting the energy efficiency standards, including providing construction material details. We can see, for example, that the regulations are working as expected with houses in the cooling-dominated climate of tropical Northern Territory, where northern orientation is less important, being less concerned with window orientation than houses in Tasmania where winter heat gain is critical.

Residential rooftop solar is being installed at rising rates. The Australian PV Institute estimates that 15.1 per cent of households in Tasmania have installed PV and 35.7 per cent in Queensland. We’re currently on track for more than half of all Aussie households to host PV by 2050, according to forecasts by CSIRO for the Australian energy market operator. Although unrelated to building standards in the National Construction Code at present, this increasing uptake of rooftop solar will have implications for future building policy.

Where to next?

Over the next few years many changes are likely to occur which will impact on the sustainability of Australia’s residential built environment. The proposed increase in the minimum energy efficiency standard in the 2022 National Construction Code update will hopefully see improvements in the performance of our residential building fabric. It may also offer an opportunity to look more holistically at housing energy demand and integrate a wider range of items through the Code, such as hot water, lighting, pool pumps, heating and cooling devices and perhaps solar systems. Under such standards new home buyers could expect much higher levels of comfort and lower energy bills than under the current 6-Star standard. The Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings should ensure that regular improvements in standards follow any step change in 2022.

These improvements to minimum standards for new houses will undoubtedly raise questions about existing houses, solar PV penetration and the use of batteries. As new houses approach zero carbon, what can we do about the rest of the stock? How can we ensure that rooftop solar supports a stable and reliable grid? What is the role of domestic batteries and how do we ensure their use is safe and economic, and supports the whole grid and not just the individual household?

Getting the word out

Builders sometimes complain that there is little demand for sustainable housing. Despite all CSIRO’s research concluding that consumers do value sustainable design, I am more sympathetic to this complaint the higher standards go. How do we ensure that consumers understand the advantages of very high performance housing? Beyond the basic costs and energy savings, a well-designed and well-constructed home is likely to have health and comfort benefits that are arguably more valuable to the householders than bill savings on their own. Research shows it is also likely to sell for a premium if its performance is disclosed. The responsibility for communicating the benefits of improved housing standards should not fall to builders, designers and energy raters alone.

CSIRO is working on all these questions, from how we manage the grid transition to accommodate renewable energy, to how to engage consumers using traditional and social media. It is also developing new energy rating tools and helping to streamline and optimise the design, assessment and marketing of energy-efficient and low carbon housing.

I frequently hear that the pace of change is not fast enough, that housing standards have not been raised since 2011 and that Australian housing performs poorly compared to other advanced economies. There is some truth to these complaints too. The emissions reduction effort required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees is enormous and the world is not moving fast enough. Residential minimum standards in Australia have not changed in almost 10 years and do lag behind some parts of Europe and America, but despite this I have seen great change over the past 15 years.

Houses are now designed to use roughly half the energy to heat and cool as they were back then. Residential PV prices have plummeted and continue to get cheaper. Housing affordability is a problem in much of Australia, but there is no evidence that energy efficiency standards are responsible for any part of the problem. In fact, a recent study by CSIRO found that lower socio-economic areas were associated with higher Star ratings than high socio-economic areas.

As I have worked to improve residential building sustainability in multiple roles over the last 15 years, I have worried about many things: the impact of Australia’s unstable climate and energy policy environment on sustainable design, the cost of minimum performance standards and the ability of the building industry to accept and adopt those standards. All those worries have proved to be largely unfounded. Despite the politics, minimum standards and the compliance pathways on which they depend have improved inexorably. The cost of implementing these regulatory changes has, in aggregate, been undetectable in property prices and may even have been delivered at a negative cost. The building industry has absorbed the regulatory changes and more as the average Star rating is creeping up without any change to minimum standards.

Conversely, I thought consumers would intuitively and immediately recognise and prefer well-designed homes rather than dwelling “like swarming ants in sunless caves”. Research suggests that while that preference does exist, more effort needs to be spent communicating the benefits of sustainable design and energy efficiency to all Australians. The important work that Sanctuary does to showcase sustainable design must be supported by well-researched marketing of high-performance housing products, by mainstream television, and by being embedded in web platforms like real estate portals and renovator forums.

The Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council estimates that Australia will roughly double its residential building stock between now and 2050. If we are to meet the Paris climate targets, residential carbon emissions must be reduced to close to zero over that same time period. Minimum standards for new housing will need to get there soonest to prevent the need for expensive retrofitting of near-new housing stock. Consumers will need to understand the benefits clearly, and the existing stock will need to be renovated, retrofitted or replaced. I am hopeful that this can be done in the next 15 years, just as so much has been achieved in the last 15.

About the author

Anthony Wright currently works as the Research Lead, Building Simulation, Assessment and Communication at CSIRO. He has previously held roles with Sustainability Victoria and private building design practices, always with the aim of turning Australian housing to the sun (with appropriate shading of course). Opinions are strictly his own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CSIRO or any other entity.

Further reading

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

All together now: One-stop shops for energy upgrades

If you want to do a home energy upgrade, it can be hard to know where to start. One-stop shops offer advice, information and referrals all in one place; we take a look at what they’re all about.

Read more Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

Case study: 130-year-old cottage goes modern electric

Not sure where to start on the electrification journey? Working with a one-stop shop can help streamline the conversion from a gas to an electric home, as Marnie and Ryan discovered.

Read more Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

In praise of Accoya

Native hardwoods are beautiful, strong and durable, but we need to wean ourselves off destructive forestry practices. Building designer and recreational woodworker Dick Clarke takes one hardwood alternative for a test run.

Read more