Shadows and light

A Brisbane architect brings all his creativity to bear on the salvage and reimagining of a humble workers cottage into his own airy green oasis.

At a glance

- 130-year-old home retained and restored

- Clever design preserves nearly half the 202m2 block as garden

- Designed for optimum natural ventilation: no air conditioning required

- Robust material palette of steel, brass, concrete and reclaimed timber

Tightly packed Queenslanders march up and down the slopes of Spring Hill in inner Brisbane. One of these is Green House, the home of Brian Steendyk of Steendijk Architects, with an oasis behind its gilded facade. It’s the third in a cluster of renovations by his practice; the reworking of each house is a unique response to local character, climate and the tight 200-square-metre blocks, but they share a common palette of folded and perforated Corten steel, timber battens, Brisbane tuff stonework, brick paving and connection to landscape.

Green House has packed in a narrow wedge of lush subtropical planting at the front to soften the facade, buffer afternoon summer sun and give back to the community. In addition to landscaping, steel and hardwood screening, eave planters and solid louvres adjust privacy, breezes and sun.

Despite the house’s dense urban setting, a sense of spaciousness has been created through careful planning (which retained 40 per cent of the small site as garden), generous ceiling heights and strong visual connection to the garden. Views have been thoughtfully framed and screened and the line between outdoor and indoor is blurred. “The backyard is a sanctuary. It’s about having a place to retreat and having a sense of repose to regroup before going out into the world. It’s a lovely space, especially in the afternoon – it’s beautifully cool,” says Brian.

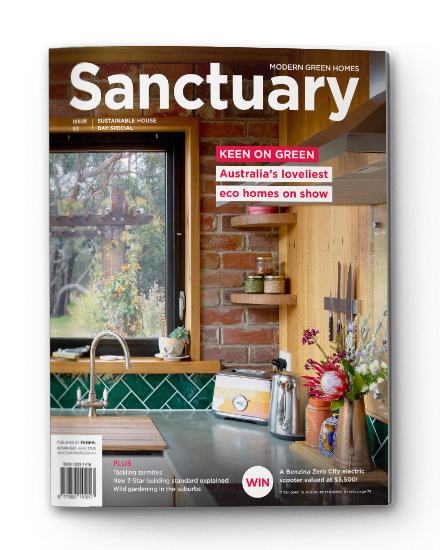

The new ground floor entry opens full width with a pivot door of steel and amber glass. Around the corner, the kitchen of grey ironbark and brass is as robust as it is elegant, and its compact footprint is expanded by reflections to the garden off its polished black aluminium side wall and mirror splashback. The lounge is an open, green-fringed garden room and shares a ceiling of exposed grey ironbark framing and flooring with the kitchen, made possible by concentrating ducting and wiring for services over the entry.

Upstairs was “butchered” in the past, says Brian. He peeled back the introduced linings and removed the spiral staircase in the middle of the building, reworking the original house level to create two bedrooms and bathrooms. Poorly repaired pine floorboards were replaced with grey ironbark to span the original joists, and recycled hardwood framing supports new walls of finger-jointed pine stained white and black to preserve the grain of the timber. The black stain to the main bedroom was about framing the views to the garden and managing light. “With a clerestory window to the gable, there’s lots of natural light, and in our climate, it helps to mitigate some of it by using a dark colour,” explains Brian. Ironbark doors were made for the bedrooms with matching solid fanlights offering adjustable privacy, light and ventilation. Two bathrooms bookend the new stairwell, illuminating it and the entry below from both sides through full walls of translucent glass.

An attic room in the high roof cavity is accessed by a tight spiral stair crafted from folded steel, and is ventilated at each end by louvres. It is key to the airflow that is the ‘breathing’ of the building. “The propensity to rely on air conditioning in Brisbane is a bit flawed given that our climate is so benign,” says Brian. “In Green House, you can manipulate the apertures, open and close different parts at different times of the day or season.” Internally, air is naturally drawn from the rear garden, cooled across the concrete slab and block walls and vented up the stairs and out of the attic louvres in a powerful thermal chimney. Louvres either side of the lounge and in the stairwell provide additional cross flow. The origami-folded Corten roof raking upward at the back doesn’t preclude winter sun, but its huge overhang and side screens protect the bedroom upstairs and kitchen below from big summer storms so doors can be opened up yet remain protected. The planter boxes provide another, softer layer of sun protection at the edges. “It feels like the garden cascades out of nowhere,” Brian explains.

Brian has made his home as robust as possible, selecting materials based on their longevity: Corten oxidises and protects itself, and clay pavers and stainless steel (for the planters and fishpond) will endure. Internally, timber, concrete block, polished concrete slab and brass need little attention and will gain character and patina with use. Each material is thoughtfully detailed not only for aesthetics but to minimise decay and maintenance – raking ends of timber battens on screens, folding of Corten screens to shed water, drainage to planters, and tiny details in the Corian bathroom linings to allow water to drain effortlessly.

Gold paint was used on the original front and rear chamferboards, inspired by the colour of the boards when 130 years of paint was peeled away. “It revealed golden hoop pine behind. It was just amazing, not a single knot. It was the most spectacular timber,” recalls Brian. “The western sun in the afternoon reflects off it and illuminates the facade.” Internally, the timber finishes are wax-based, avoiding the issues of cupping in a humid climate and simplifying refinishing down the track.

Green House is a contemporary adaptation of its character home bones, with the new clearly expressed in materials set to become richer over time. The Steendijk Architecture team’s passion for ‘quality over quantity’ is exemplified here as is their deep understanding of climate-responsive design. “Occupying the Green House is like sailing a yacht; you modify and manipulate its form and skin to seasonal conditions and natural elements and work with these to maximise the performance of the building,” says Brian.

Insights

“Layering and changeability is the key. Occupying the Green House is like sailing a yacht; you modify and manipulate its form and skin according to seasonal conditions and natural elements, and work with these to maximise the performance of the building.” – Brian Steendyk, architect and homeowner

Further reading

House profiles

House profiles

New beginnings

Catherine’s new hempcrete home in the Witchcliffe Ecovillage, south of Perth, offers her much more than simply a place to live.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Greenhouse spectacular

This Passive House is comfortable throughout Canberra’s often extreme seasons, and has a greenhouse attached for year-round gardening.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Like a charm

A smart renovation vastly improved functionality and sustainability in this small Melbourne home, keeping within the original footprint and retaining the cute period character.

Read more