Airtight design

If you’re planning to build an airtight home, it’s important that you also consider indoor air quality. We ask building scientist Jenny Edwards to tease out the issues around mechanical ventilation with heat recovery – including when it’s needed and when it’s not.

Draughty buildings (energy assessors call them ‘leaky’ buildings, because they leak air) drive up energy bills. In winter they lose warm inside air, and in summer they let the heat creep in, pushing up energy consumption in both extremes. The more airtight your home, the easier it is to stabilise and control the indoor temperature.

But very airtight buildings, although they’re more energy efficient, can have a different problem: air quality. If your home is sealed up tight against the cold through the winter months the air can get stale and stuffy; vapour can accumulate causing condensation issues and carbon dioxide and indoor pollutant levels can go up.

To solve the indoor air quality problem, some homes are fitted with mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) – a relatively new technology that’s arrived from Europe. These devices provide fresh, pre-heated or pre-cooled air into well-sealed buildings.

The catch, of course, is that they cost money to purchase, install, maintain and run; so it’s important to figure out if you actually need one before going ahead. But first, what is MVHR, anyway?

Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery

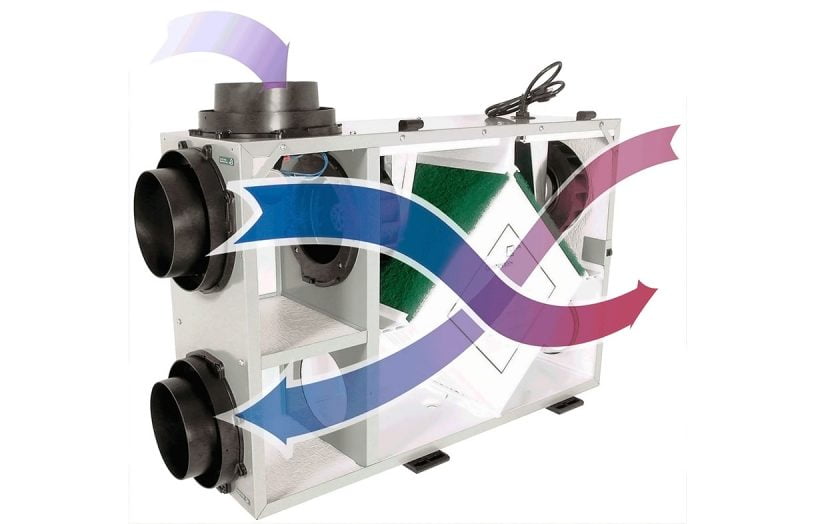

The basic idea is that the ventilator warms (or cools) incoming air by exposing it to the outgoing air. The fresh air coming in doesn’t mix with the air being vented out, at least not directly. The various MVHR products do this in a variety of ways: the two air streams may pass next to each other through ceramic pipes, for example, or through aluminium ducts; or there might only be one vent, switching back and forth between extraction and injection. In all cases, it uses the mild air from inside your home to take the bite off a stream of outside air.

All the available models also filter the incoming air, as well as modulate its temperature. This can make them attractive for allergy sufferers and people living in areas of high outdoor pollution.

MVHR isn’t a heating or cooling system

The MVHR system itself doesn’t heat or cool anything. It can’t warm up a cold house in winter and can’t cool it down in the heat of summer. All it can do is help keep the home at the temperature it’s already at.

MVHR is useless in a leaky house

If your house has draughts, if it has cracks and gaps letting in the outside air, then MVHR is not going to make much difference, if any, to your comfort. Sure, it can provide a stream of filtered air of mild temperature for you, but that won’t stop the stream of unfiltered air that’s already coming in, that’s making you cold in winter and hot in summer (remember, MVHR is not a heating or cooling system). If you have a leaky house the priority is to make it less leaky. Only after you’ve made it more airtight might you want to consider MVHR.

If the outdoor air is mild and clean, just open a window

MVHR offers the most accrued benefits for very airtight homes in extreme temperature zones, or where outdoor air quality is bad. If you live in a temperate location with clean outdoor air, then the easiest and best way to freshen your indoor air is to open some windows.

If you don’t have openable windows to allow cross ventilation, then make that your priority. Don’t go high-tech if low-tech is enough.

How to assess your home

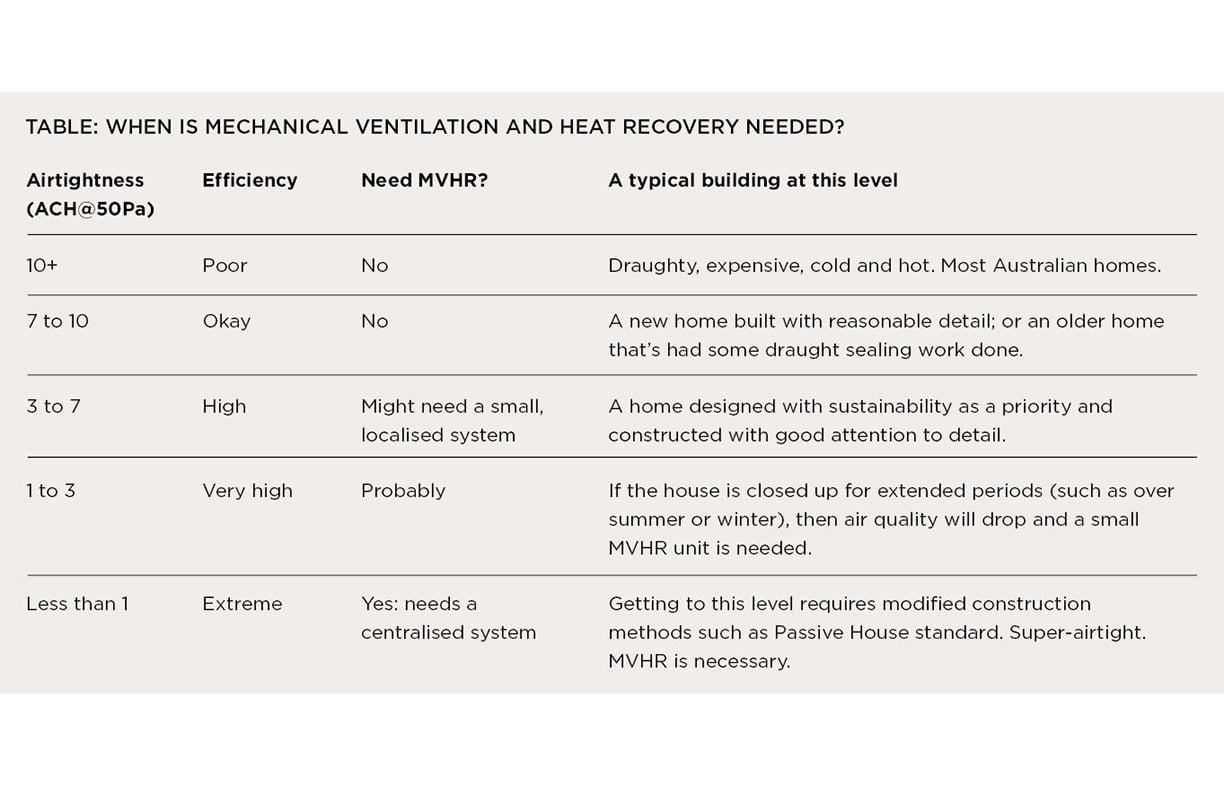

The benefits of MVHR depend above all on the airtightness of the house. In order to decide whether your home needs such a system, then you need to measure its airtightness. You do that by hiring an energy assessor to come to the house to do a blower-door test.

The blower-door test measures airtightness according to the international standard, in air changes per hour at 50 pascals, which is a mouthful, even when abbreviated to ACH@50Pa. The point is that you need to know that number.

Most Australian houses get an airtightness score of 15 or above, which is far from good but most people don’t care because they don’t realise how much better it can be. A house at 10 is much more comfortable than one at 15, and one at 7 is more comfortable again. Indoor air quality can be compromised below 3ACH, so that’s when MHRV is needed (see table).

Air quality

If a building is in the airtightness range between 3 and 7ACH, or if you’re otherwise not sure if you need MVHR, then measure its air quality.

There are numerous data loggers and measuring devices available for reasonable prices. The ideal range for carbon dioxide is between 400 and 1000 parts per million (ppm), although the risks of carbon dioxide only become acute above 5000 ppm. It is common for homes to exceed 1000 ppm at times, including very leaky homes, but if you are consistently averaging above 1000, then a MHRV might be a way to bring it down.

An airtight house might be at risk of high vapour levels (leading to condensation and ultimately mould). If your home is consistently reaching and staying over 70 per cent humidity (and has an airtightness level less than 7ACH) then MHRV could help.

Pollutant levels are harder to measure but are likely to correlate with carbon dioxide and vapour build-up, so measuring those two is likely to capture the overall air quality issue for your home.

The sweet spot: quite tight but no need for MVHR

It’s possible for a home to have good airtightness levels, yet not require an MVHR. That’s at airtightness of between 3 and 7ACH. Such a home must also provide the ability to vent when necessary by opening doors and windows to create cross-draughts; and not be situated where outdoor pollen, pollution or sustained extreme temperatures are a major issue. These houses must also have appropriate exhaust fans installed in bathrooms and kitchens to remove water vapour and manage moisture levels.

I have been involved in the design and assessment of over 100 houses in this range, and have found that air quality is almost always fine. In the rare situation where it is compromised in the 3 to 7ACH range, it’s because of additional factors such as indoor wood heaters, gas cooking or incorrect use of exhaust fans. [For more on condensation see further resources.]

If you need to install one, what sort of MVHR system should you get?

Once you decide that MVHR is required, selecting which unit is most suitable is the next step. Renew magazine recently published an excellent heat recovery ventilation system buyers guide which outlines the models currently available in Australia.

I suggest you check that out to investigate the various options open to you.

Considerations

There are costs involved in MVHR including the cost of the equipment itself, installation, running costs and maintenance. Therefore, it is imperative that you do your research and make sure you need one before installing it. I suggest taking a methodical approach to assessing the health of your building, as this is a relatively new technology in Australia and there are still very few sources of independent local expertise.

Find out what the airtightness level of your home is: if it’s greater than 7ACH, there is little to be gained from an MVHR; if it’s less than 3ACH you probably should get an MVHR and if less than 1ACH then you should definitely get MVHR (very few homes other than those built to Passive House accreditation levels have an airtightness below 1ACH).

If you’re unsure, purchase a data logger and use it to monitor your humidity levels, CO2 levels, or both.

Further reading

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Condensation management

It’s important to consider both ventilation and moisture control in order to avoid condensation problems. Jenny Edwards recommends a holistic approach.

Read more Research

Research

All-electric solar homes save thousands over gas: report

New homes that are all-electric and have solar power will save their owners thousands of dollars according to a new report by Renew.

Read more Research

Research

Consumers are moving away from gas

Consumers are less likely to choose a gas appliance than they were five to 10 years ago, according to a Renew survey.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Fresh air without the heat loss (or gain)

Clare Parry explains what mechanical ventilation is and why we might want to use it as our homes become better sealed.

Read more