Tropical heat

This award-winning home demonstrates design for a comfortable lifestyle in the tropics – without air conditioning.

Sitting comfortably on a stringybark bushland block south of Darwin, the airy steel-framed home of Geraldine Lee and Kristian Mortlock demonstrates just what is possible when architect and owner-builder share a common vision for passive design in the tropics. Small by today’s standards at only 75 square metres plus a verandah, the house is a study in appropriate design for this region, with the emphasis firmly on passive cooling rather than the ubiquitous air conditioner. Indeed, this was part of the brief to the architect, Greg McNamara of Troppo Architects. “We were adamant we didn’t want air conditioning in the house,” Geraldine says. “We were looking for a naturally cooled house where we could live comfortably in the tropical environment.”

Keeping cool in the tropics is no easy task. Like the rest of the tropical north the region has two distinct seasons: a cool, pleasant, dry season from April to September; and a hotter wet season from October to March characterised by storms, monsoonal rainfall and the ever-present threat of tropical cyclones. To handle the climate, every opportunity has been taken to promote natural cooling in the house. The interior spaces soar to an impressive five metres above the floor, and shutters located at the peak of the raked ceilings can easily vent rising hot air.

The house’s unusual cruciform plan was presented by their architect at an early meeting. “It was different from any of our sketches,” says Kristian, “but Geraldine and I were instantly drawn to the idea and we knew that this was the house for us.” The house is raised above the ground on short piers, creating minimal disturbance to the landscape – an important consideration that saw the house designed around a mature Ironbark tree and several rare cycads. A long verandah cuts through the house forming the main circulation spine. At 85 square metres, it more than doubles the home’s living space and teams with the many louvred windows to allow natural light and ventilation to permeate the building.

The western arm of the house contains space for two bedrooms and a compact kitchen and living area. To the south and east across the verandah are the main bedroom, bathroom and a clever mezzanine providing a quiet retreat for the parents. Quirky details such as slicing off the end of the house at an oblique angle enhance views out to the landscape. “Our place is very similar to the house I grew up in,” Geraldine says. “Modernised, of course, but the basic elements are all there.” Historical precedent is a compelling design tool for the tropics, where the fundamental elements of an appropriate architecture have been shaped over decades.

Construction techniques were tuned to the skill set of the owner-builder: Kristian, a sheet metal worker specialising in stainless steel fabrication, undertook much of the construction work himself. As a consequence steel is ever-present, from the main structure and external cladding to the interior finishes, where it’s used for bench tops and the large sliding doors that open up the living space.

One of the advantages of being an owner-builder is having the time to review the design as the house progresses. A telling example was the decision to omit a row of vertical louvres along the verandah designed to block the setting sun. “We were willing to sacrifice a couple of hours in the afternoon to have a clear, unimpeded view of nature while seated on the verandah,” says Geraldine.

Solar energy is harnessed to provide hot water and also electricity, with the excess fed back into the local grid. The inclusion of grey and black water recycling was considered but costs proved prohibitive, so the house is connected to a standard septic system, with funds directed towards water tanks instead. Geraldine and Kristian chose energy- and water-efficient fixtures and fittings wherever possible, and a desire to reduce embodied energy guided many material choices: a difficult task in a region far removed from manufacturing bases.

Indeed, one of the more frustrating aspects of building was dealing with local suppliers. “Anything non-standard had to be ordered at our risk,” says Kristian. “We also had difficulty finding information on sustainable practices,” notes Geraldine. “For example, in selecting timber flooring there was very little information on what we should use, and Darwin is not ideally positioned to access recycled timbers, as there is next to nothing available locally. We looked into flying down south to inspect and purchase, then transport back, and this proved to be non-viable.” After much research, Spotted Gum from sustainable forests in Australia was selected for interiors and decking, while Ironwood salvaged from clear felling of native forests on Melville Island (to make way for plantations of fast-growing trees) was used for structural elements wherever possible.

Ultimately, however, the couple is very happy with the outcome: a beautiful house in the bush that is economical to run, will require little maintenance and is an elegant response to the challenges of living sustainably in a tropical climate. The Australian Institute of Architects concurred, awarding it the Burnett Award for residential architecture as part of the 2011 Northern Territory Architecture Awards.

Moving in just before Christmas 2010, Kristian and Geraldine have already experienced the full range of climatic conditions including a tropical cyclone, wet season rains that delivered almost three metres of water, and the coolest of dry seasons during which temperatures dropped to 10 degrees in the early mornings. ”It was a little damp during the cyclone,” says Kristian, “but we experienced the extremes of nature, and the house responded well.”

Further reading

House profiles

House profiles

Airy flair

A minimalist renovation to their 1970s Queenslander unlocked natural ventilation, energy efficiency and more useable space for this Cairns family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Pretty in pink

This subtropical home challenges the status quo – and not just with its colour scheme.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

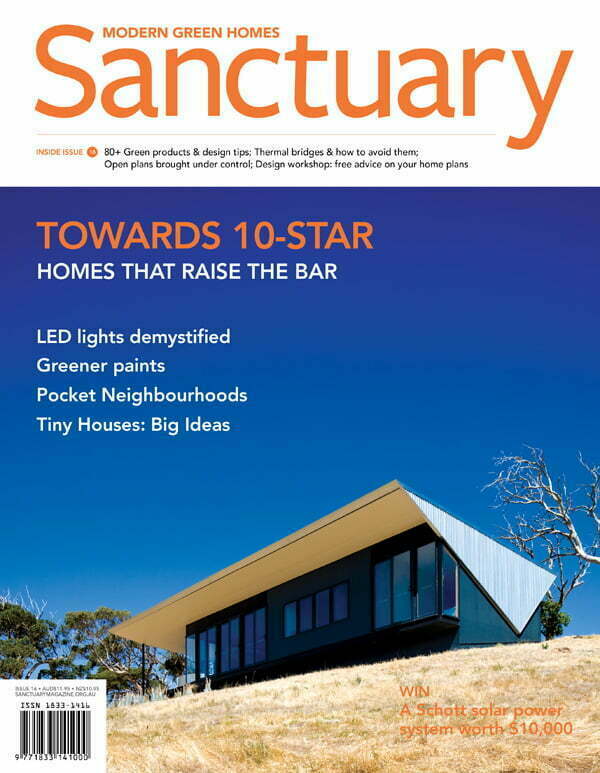

Mini homestead

A small off-grid home in rural Victoria, built to a simple floor plan.

Read more