Material difference

Homeowner Danny Mathews had plenty of ideas and knowledge about low impact materials and how to use them to improve his period cottage, but he sought the guidance of architect Penny Guild to make it happen.

Danny Mathews wears many hats: musician, ‘deep green’ developer, and environmental philanthropist to name just a few. He has lived in his Victorian-era, double-fronted weatherboard cottage for 25 years, and while better insulation and retrofitted double glazing have helped improve its performance, those changes were not capable of entirely overcoming its poor orientation.

Danny currently lives alone but has had friends move in for extended periods over the years, and he often entertains and hosts music sessions, so he was keen to create a more appealing and sunnier living area.

As one of three developers behind the sustainable Mullum Creek subdivision in Donvale, a suburb on Melbourne’s eastern edge, Danny had clear ideas about the passive design basics he wanted to employ and the aesthetic he aimed for. Several people recommended he approach architect Penny Guild and when they met, they discovered many common links, including a clipping that Danny had collected about one of Penny’s earlier projects.

With shared interests and mutual friends, architect and client seemed destined to work together. They established an easy rapport that continued throughout the two-year design and build process.

In his brief, Danny told Penny he wanted “more views to the sky and better connections to the garden”. Thanks to the design guidelines that he’d helped to develop for Mullum Creek, he knew which materials he wanted to build with, too.

“I wanted lightweight construction, with no structural steel or CCA-treated pine [chromated copper arsenate], so we were looking at LVLs [laminated veneer lumber] for the framing,” he says. “Also, because I didn’t want to lay a concrete slab, I was thinking about options to achieve thermal mass with other materials.”

It was quite a comprehensive wishlist and Penny readily admits that Danny’s sustainable design knowledge rivalled or even surpassed her own.

“Danny had been living there for two decades, and he’d been thinking about renovating for 12 years, so he’d considered so many options,” she says. “He’s very knowledgeable about environmentally sustainable design and has many friends who are gurus in the field. But the danger in knowing so much is that you can be overwhelmed by ‘choice anxiety’ and become paralysed, because you always feel like there might be a better option.

“As an architect, you get good at making a decision, even though you understand that there are many possible good decisions,” Penny says. “There isn’t just one right answer, so you have to agree on a course of action, and work through any challenges as they arise.”

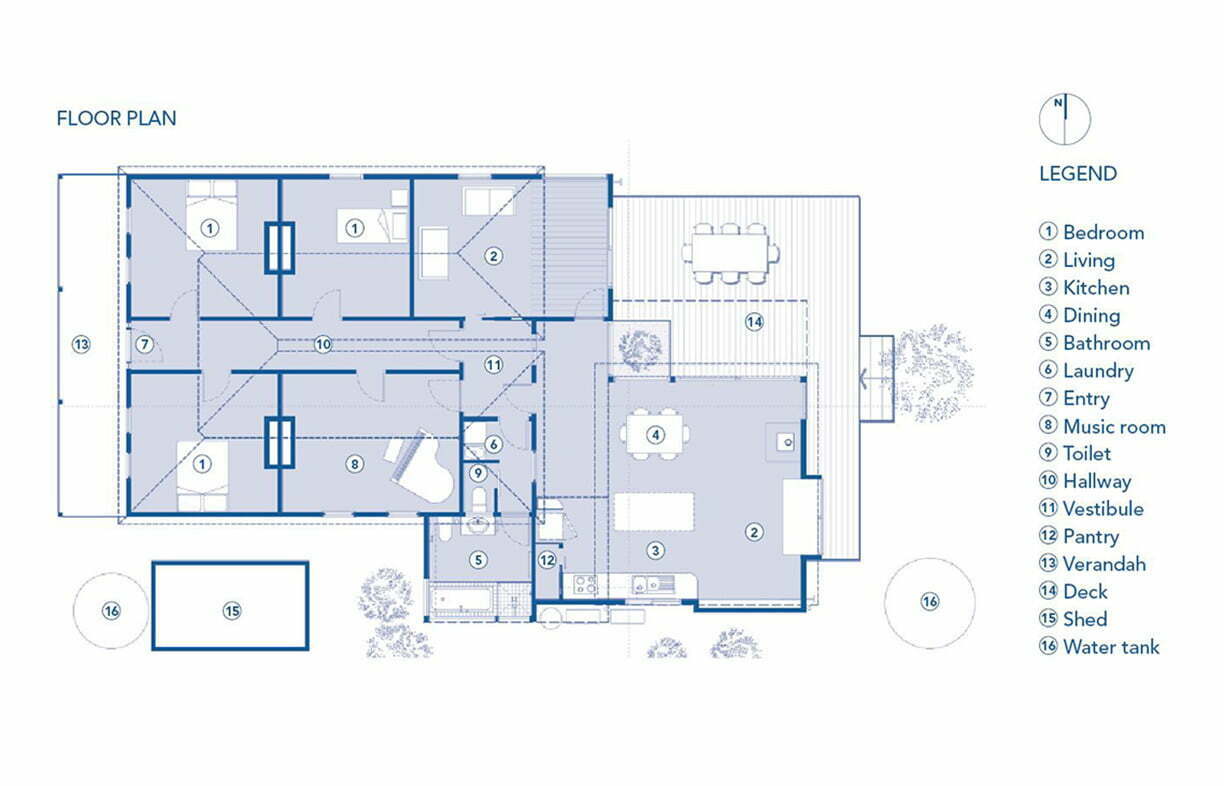

Together, Danny and Penny agreed on a simple addition at the rear of the cottage, which houses the kitchen, dining and living spaces, with plenty of glazing to capture views outwards in all directions. This new box was deliberately pushed towards the southern boundary to maximise northern light, and it opens to a large sunny deck.

In line with Danny’s wishes, the existing rear wall of the cottage remained intact, and a new bathroom was tucked to one side. The loungeroom – which was cold and dark – was converted into a dedicated music room, and the third bedroom was extended slightly – using the footprint of the old kitchen – to create a new living room that benefits from easterly light.

Even though the design aimed to maintain as much of the old house as possible, and make the new section deliberately compact, the project has transformed the way the house is used. When Danny is home alone, he can occupy just the new section, but there is plenty of space for several adults to cohabit and share the space, and the house provides an ideal backdrop for regular gatherings and entertaining.

The new room is highly flexible and can be easily rearranged thanks to a portable island bench, while the 1960s-inspired Marmoleum floor – with a custom-designed tile pattern – feels great underfoot and is an excellent surface for dancing, Danny says.

“It’s a great party house because you can move things around to accommodate a small band, or to set up a big table for Christmas feasts,” Penny says. “And when Danny is the only one home, he can shut the doors and not heat or cool the rest of the house.”

Being an inventive environmentalist, Danny wanted to experiment with low-cost sustainable technologies, including an unconventional take on thermal mass. “We were interested in installing thermal mass that could be switched on or off, and that had low embodied energy,” Penny explains.

“Thermal mass can be useful, but I didn’t want the high embodied energy of a concrete slab, and recycled bricks didn’t fit with my aesthetic,” Danny adds. “But water provides high quality thermal mass, and is potentially good in retrofit situations, especially if people are on low incomes or renting.”

However, they discovered that there is little formal guidance on the topic, so they worked through various options together. “There is no one-size-fits-all formula for how much water to use, and how to use it, and where to place it,” Danny explains. “Initially I looked at installing a large tank, but I realised the rate of absorption of heat would be too slow. It was important to use a container size that worked within the human habitation period, which in my case is from about 5pm to 11pm, to get the benefits while I am using the room.”

Danny had a set of custom shelves made using recycled timber, which can be moved into the path of winter sun, and he has experimented with different containers – including three- and four-litre olive oil tins, 375ml drink cans and various sized HDPE milk bottles.

“The HDPE and aluminium cans behaved in almost the same way, but not everyone wants a wall of plastic milk bottles in their living room,” Danny says. “I’ve decided to use olive oil cans because they are the right size to absorb and release heat for that crucial time frame, between when the sun goes down and when I go to bed.”

Another low-tech, low-cost solution is the ‘heat transfer unit’, which combines a tube of air conditioning duct that runs above the ceiling to connect the new room with the music room. It’s fitted with an inline fan and thermostat, and in winter, it moves warm air from the extension to the old part of the house, raising the temperature by three or four degrees, Danny says.

“In terms of thermal performance, the old Victorian part of the house performs better in summer, while in winter the new section is more comfortable,” he says. “It helps that I’m a low energy user and I’m tolerant of cold. I didn’t have any heating before the renovation, and I still wouldn’t turn on the AC unless the indoor temperature rose above 30 degrees Celsius.”

Danny has lived in the upgraded house for more than a year and plans to complete a few more tasks to tweak its performance. “I’ll install recycled curtains and blinds in the new room, and more external shading, but it works really well so far,” he says. “I’ve also realised there is a lot of radiant heat coming off the external deck, so I plan to put more pot plants out there and add more external blinds.

“All houses have these quirks and I’m happy to make seasonal modifications to overcome them.”

For both client and architect, the most successful aspect of this project is the way the new room connects to the garden, especially the daybed, which appears to be perched in the adjacent tree canopy.

“When we first met, Danny told me that he loved the old back part of the house, with its natural light and views of the garden,” Penny says. “We wanted a design that worked with Danny’s retro and vintage furniture and objects that he’s been collecting for years, and that captured the essence of what he loved, and I think we’ve done that.”

More sustainable renovations

House profiles

House profiles

Airy flair

A minimalist renovation to their 1970s Queenslander unlocked natural ventilation, energy efficiency and more useable space for this Cairns family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Doubling up

The why, how and where of building a secondary dwelling.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Red brick reno

After years of gradual upgrades, this leaky brick cottage in Central Victoria is now an exemplar of comfortable, efficient, low-bills living.

Read more