Sustainable carpet choices

While rustic floorboards and polished concrete have long been the mainstays of sustainable design, carpets are still often used in bedrooms for their softness and insulating qualities. Interior designer and healthy home expert Melissa Wittig helps you tread the woven path.

Environmental impact

While thermally massive materials such as concrete and tiles are often preferred for living spaces to help moderate temperatures, carpet does have benefits in the right space, offering warmth underfoot, noise reduction and insulation. However, the environmental impact of carpets varies widely. One of the primary issues is the relatively short life cycle of some carpets when compared with hard flooring materials.

Agriculturally sourced fibres have wide ranging impacts depending on the intensity of production, land and water use and the related outputs of the farm. Life Cycle Assessments (LCAs) aim to cover all of these aspects, but for agricultural commodities this is inherently complicated and not all assessments will cover farm processes.

The need to regularly vacuum carpets to lengthen life, maintain appearance and reduce dust should also be considered alongside the embodied energy – that is, all the energy required to produce and distribute the product for use. a

Carpets are recyclable, but current rates of recycling or reuse in Australia are low. When carpets are recycled, only one reuse is generally possible, with around 25 per cent of the carpet likely able to be reused as carpet, a further 25 per cent could be retained for carpet backing and half the carpet sent to landfill where it could take up to 50 years to break down, releasing greenhouse gases in the process. And of course some components of nylon and synthetic materials from petrochemical origins will never completely break down.

Some manufacturers operate their own recycling programs and will collect your old carpet for reuse as part of the installation agreement, though this is more common for commercial properties. Meanwhile, innovative programs such as one at Deakin University are working to reuse carpet and textile polymer waste in concrete.

What’s in my carpet?

The components of carpet are cushion or underlay, adhesive and carpet.

There are generally two categories of materials that can be used on their own or blended to create carpets, natural or synthetic. However, more recently we have begun to see the production of alternative composite material carpets, such as those made with recycled plastics or even fishing nets.

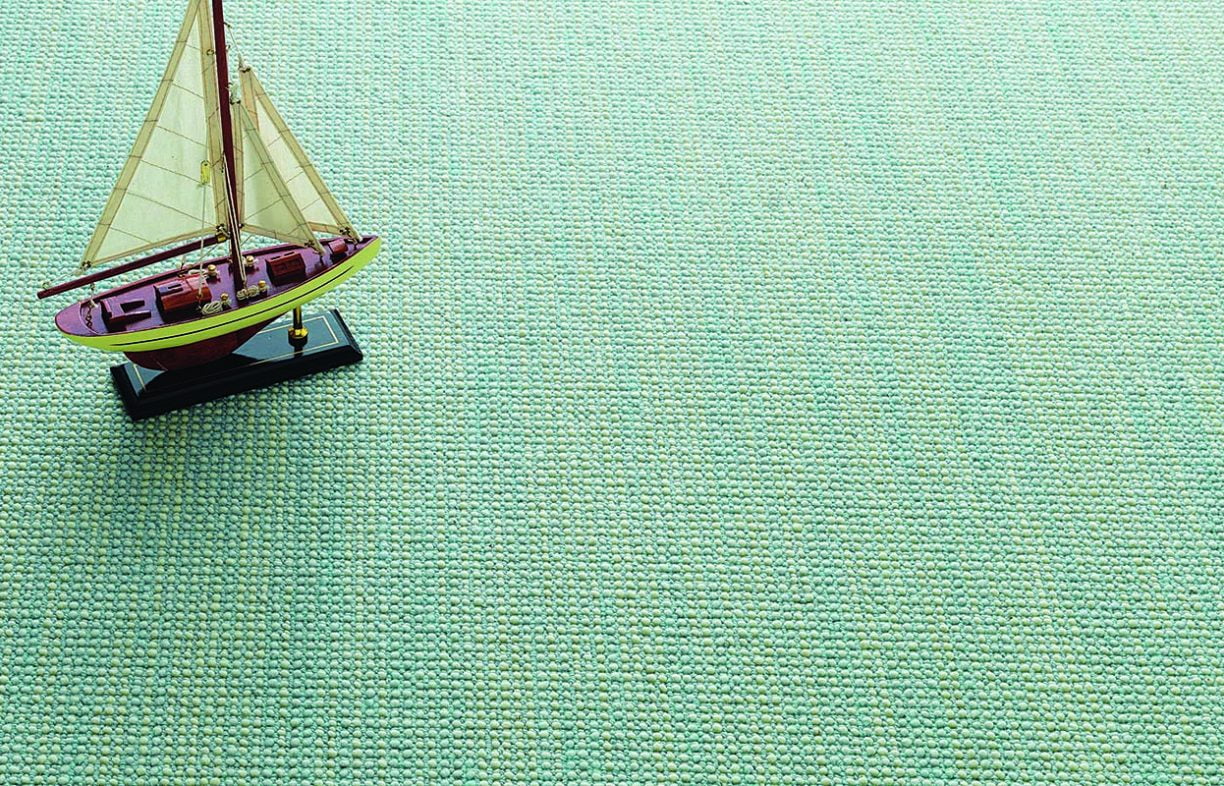

Synthetic fibres are man-made materials such as nylon (polyamide), polyester (PET) and polypropylene (olefin) and are most commonly used in carpet production. Alternative, natural fibres such as sisal, jute, coir and seagrass are growing in popularity, partly because they can be grown without chemical input and are naturally antimicrobial. However, natural fibres such as these can be susceptible to moisture so may not be suitable for humid climates.

Wool has strong insulative potential and is also naturally antibacterial. The practices and environmental impacts of sheep farming in different countries vary greatly, depending on the climate and what else the farm is producing. Land and water use, methane pollution, and soil degradation through acidification and eutrophication are also potential issues.

Both natural and synthetic materials can require energy intensive manufacturing processes, and all fibres will vary in grade and quality. Though natural fibre products can be more environmentally friendly than synthetics they can also be less durable, and obviously frequent replacement of flooring defeats the environmental objective. A true comparison on material type would need to be context-specific based on an LCA of materials, production, use and replacement and end-of-life considerations. The type of fibre used in a carpet will contribute to its durability, flammability, pile retention, colour fastness, stain resistance and pest resistance.

While some fibres such as wool have inherent characteristics like high UV protection and ignition thresholds, making them fire resistant, other fibres require additives. Chemicals are often used on carpets to provide or improve dust, mould, stain, flame and insect resistance. The ‘new carpet’ smell we’re all familiar with is essentially volatile organic compounds (VOCs) being emitted (but it is also important to note that VOCs do not always have an odour). While wool fibre has been reported as being able to absorb and trap VOCs this is not the case for most synthetic fibres.

Carpet backing and underlay

Carpet backing is placed underneath the carpet to provide longer life, additional comfort, insulation, and noise reduction. In some cases a cushioned secondary backing is integral to the carpet backing. The backing material of a carpet also contributes to its sustainability and VOC emissions. For example, rubber backing, while a good insulator, tends to have higher VOC emissions than jute fibre. PVC backing with 100 per cent recycled material is available and used by some manufacturers, but is not yet standard. Foam backing is also popular and is cheaper but less hardwearing. Felt backing, produced from plant fibres, which is also insulating and soft underfoot could be a good option. Fibre treatments listed above also have the potential to release emissions into indoor air over time.

Chemical adhesive used during installation is often toxic and can off-gas. It is also a key inhibitor to sustainability as it limits carpet removal and reuse. Non-toxic adhesives and adhesive-free pressure application systems are available, but may not be offered by all manufacturers.

Certification programs

There are no specific import standards for carpets in Australia, and while the general requirement under Australian Consumer Law is that products must be durable, safe and fit for their intended purpose, in reality laws do not require carpet imports to be accompanied by full documentation. a

Ingredients of concern in carpets made to inferior standards may include banned dyestuffs such as AZO dyes that have been found to be toxic, or fibre chemical treatments not accepted or tested as safe in Australia.

Independent certification programs can assist with navigating product choices. The Carpet Institute of Australia runs a voluntary grading system, the Australian Carpet Classification Scheme (ACCS), available to all companies local and abroad as well as the voluntary Environmental Certification Scheme for Carpets. All participating companies must meet performance standards for raw materials, manufacturing, installation, use and final disposal and recycling or reuse. The Environmental Certification is a four-level program, with producers certified above level 2 able to contribute to Green Star building ratings.

Other certifications that carpets can carry include the Woolmark/Woolblendmark label and New Zealand’s Fernmark label for wool content.

There are many certification programs around the world that assess products to varying standards. To avoid greenwashing, read the certification criteria to understand what characteristics have been assessed. If a product has a ‘green certification’, this does not necessarily mean it is a healthy product option. For example, a product may be made with renewable materials in a resource-efficient way yet still have high VOC emission levels. The Environmental Certification Scheme for Carpets mentioned above does consider total volatile organic compounds, and the Carpet Institute of Australia provides a list of certified carpets and suppliers at their website. Other organisations in Australia that certify environmentally friendly carpets and floor coverings are Good Environmental Choice Australia (GECA) and Eco Specifier.

Unfortunately the current voluntary nature of product assessment leaves many consumers in a vulnerable position. It would be great to see industry product assessment in this sector become mandatory so that consumers can make informed decisions about a product’s materials, quality, sustainability and health credentials based on testing outcomes displayed on labels.

- Ask questions about: where and how the carpet was made; transportation required; raw material use and sourcing; additives and treatments used; VOC emissions testing; independent certification; installation requirements; maintenance and warranty period; end of product life programs

- Choose colours, textures and patterns that will transcend fashion

- Opt for manual installation or fixing methods rather than adhesives to avoid pollutants and VOCs

- Keep a record of the manufacturer, carpet name or code (batch code if possible, as colours can vary), grading registration number, retailer details, type of underlay used, date of purchase, installation date and purchase receipt in case of warranty or insurance issues in the future

- Consider UV protective window glazing, curtains, blinds or awnings to protect carpet from prolonged periods of direct sunlight – this will help minimise colour fade and deterioration

- Keep windows and doors open for as long as possible at installation to air the carpet and reduce VOC pollution

- Use furniture cups to protect carpet from compression under furniture legs

- For people with allergies or chemical sensitivities, investigate individual products, fibre characteristics and maintenance needs before purchase.

This article was published in issue 31 of Sanctuary magazine