Playspaces: Child’s play gets serious

The importance of play is a hot topic in child development circles. We investigate the changing thinking behind playspace design and how playfulness can be incorporated into all kinds of spaces, both public and private.

Have you ever thought about how important opportunities for play are in your neighbourhood? The community in Eltham in Melbourne’s bushy north-eastern suburbs was forced to think deeply about the subject in December 2017 when the much loved 25-year-old Eltham North Adventure Playground was burnt to the ground.

Innovative when it was first built, some wanted the playground to be rebuilt exactly as it was, but others saw an opportunity for some re-evaluation. For Nillumbik Council Mayor Karen Egan, the fire highlighted community spirit and encouraged locals to think deeply about what they valued. “Our community was devastated when we lost the original playground, but despite this, everyone came together to rebuild this much loved park,” she says. After a collaborative redesign process, the playground was rebuilt closer to the bush and Diamond Creek, allowing for more exploration in nature, and it was made more inclusive and accessible to all in the community.

The importance of play

As the Eltham community’s experience shows, the way we think about play has evolved in the past couple of decades. Concern about growing urbanisation, the spread of digital technology and increasingly sedentary lifestyles has generated much research into the importance of play and types of play, and it has emerged as fundamental to the development of healthy children along their path to adulthood.

Australian playspace designer and commentator Fiona Robbé believes that ‘deep’ unstructured play is crucial to our cognitive development. “Play is a means of learning to live, an interactive exploration of the possibilities of this world and our place in it. Instinctive, voluntary, spontaneous play is vital to develop the potential of all children,” she says.

Getting back to nature

Among all the different ways we can play, it is nature-based play that has exploded in popularity across Australia over the past few years, in our neighbourhood playgrounds, our schools and even at home. Often incorporating constructed water courses, uneven rock and timber surfaces, insect and bird attracting plantings, and loose materials such as sand, pebbles and mud, these emerging innovative spaces facilitate an engagement with the natural world that researchers in the child development space say is crucial to the healthy growth of children’s minds and bodies. As Richard Louv, prominent American writer and thinker on play and creator of the term ‘nature-deficit disorder’, says: “Time in nature is not leisure time; it’s an essential investment in our children’s health – and also, by the way, in our own.”

Moreover, the provision of natural spaces that facilitate open-ended and unstructured play has been shown to encourage healthy risk-taking, collaboration and problem solving, exploration, discovery and spontaneity. The natural learning that is a positive byproduct of play in these environments helps children grow into healthy, resilient adults who are comfortable in nature and can thrive in a changing world.

Where we were

To gain an appreciation of where play is now in Australia, however, we need to take a short journey back to where play has been in recent decades. Many reading this article will be old enough to remember the playgrounds of the 1960s to the 1980s. Largely constructed of steel and wood, they usually consisted of a set of swings, some monkey bars, a slide, see-saws and if you were lucky, a merry-go-round or a rocket to climb on. By the 1990s, the risk of injury associated with such playground equipment saw its replacement with plastic playgrounds on rubber matting, carefully designed to be safer. These playgrounds may have suited an increasingly risk-averse Australia, but they tended to be boring for children because they offered only structured and predictable play opportunities.

Walking into many of today’s nature-based playspaces, you’ll notice far less emphasis on once common ‘play equipment’. In fact, you may be forgiven for wondering if you’re in a playground at all.

Putting the real play back in playgrounds

In the newly completed Bangalow Weir Parklands in northern NSW, the only piece of traditional play equipment is a stainless steel slide, but even this follows the existing fall of the land rather than being built up high. Conceived and constructed on a tiny budget, the playspace’s real stars are its natural features, according to landscape architect Dan Plummer. Working with the natural, undulating topography under a canopy of mature trees, and using local decommissioned bridge timbers, a less-is-more approach was applied to the design. Natural passageways and satellite clumps of vegetation were linked to provide a simple template to encourage exploration and discovery of the natural spaces. “The key to the playground and why it is so lovely is that we had those cracking trees to work with,” says Dan.

Across the continent in Adelaide’s Morialta Conservation Park, a dreamtime-inspired playspace has been created in Muka Muka Rrinthi. The designers, Climbing Tree, worked with local school children and Indigenous traditional owners to create a play environment that would set anyone’s imagination running wild. There’s an enormous dreamtime snake to explore, huge ‘bird nests’, build-your-own stick cubbies and stone climbing walls, and the entire space is peppered with stencilled and carved Indigenous motifs. Although a steel slide was included, for Climbing Tree’s former-schoolteacher designer and builder, Simon Hutchinson, that’s not where the attraction lies. “The slide only holds the kids’ attention for ten or fifteen minutes, but the natural creek right next to it engages them for hours. Watching kids play in a space like that is wonderful because they clearly love those wild spaces,” he says. “The more open ended you make a play area, the more you allow kids to use their imaginations.”

The recent big shifts in the design of play environments have not been without their challenges. Hobart-based landscape architects Playstreet have designed around 70 natural playspaces for Tasmanian schools, and practice co-director Miriam Shevland likes to tell the story of how one of their projects was so successful it was almost loved to death within weeks of opening. “The school was horrified that the kids had dug up all the gravel and made enormous dams, but we thought ‘this is sensational – they’re actually using it!’ There were now hundreds of kids using and loving a space that was previously just a patch of lawn,” she recounts. Messy it may be, but the benefits to children’s development mean there is no slowing of the nature-play movement.

Play for everyone

Building inclusivity and universal design principles into Australia’s playspaces so that they are accessible, stimulating and fun for all is a relatively recent positive development, and there have been some real champions for change.

Caroline Ghatt and her partner Tim Smith had just about given up trying to find a playspace near their home on Sydney’s Northern Beaches to take their intellectually and physically impaired 11-year-old son Marcus. What began as a Facebook rant to their local mayor has now grown into a collaborative social enterprise, Play for All Australia, through which they assist councils to build inclusivity into their playspaces. The organisation has now worked collaboratively on five Sydney playgrounds, designing universally accessible, rich sensory spaces that are a joy for all children to experience.

“The days of speaking about inclusive playgrounds as separate or special are definitely behind us,” Caroline says. “Play is play; kids don’t see it any differently.” She contends that designing for inclusive play is more limited by imagination than it is by budget.

Play at home

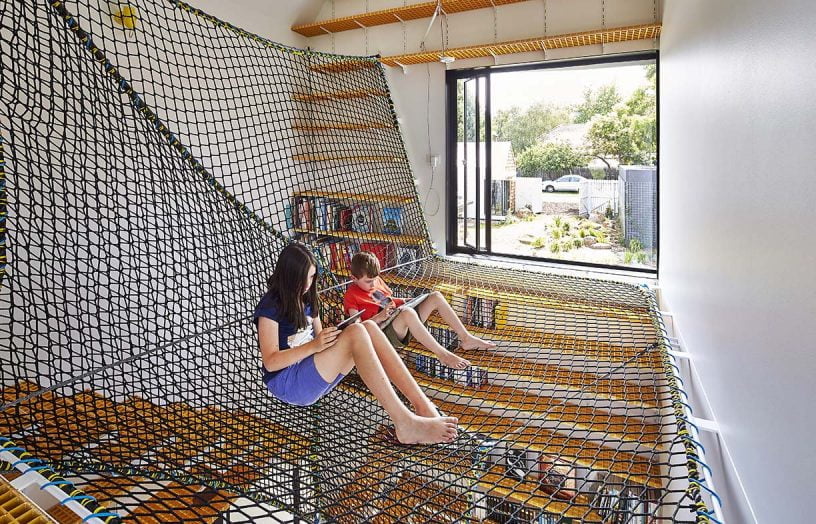

Playgrounds are one thing, but what about including opportunities for play and playfulness in the design of our homes? One architectural practice where such considerations are front and centre is Austin Maynard Architects, who incorporate both visual playfulness in their designs and a sense of play in how they function. “Many of the people that come to us have young kids, and our focus is on designing a home that is enjoyable and fun for everyone,” co-director Mark Austin explains. “There is an intrinsic informality with all our projects, which adds to the playfulness.”

Some of their creative ideas include netting across voids for relaxing or climbing, steps built into walls to encourage exploration, under-floor toy storage boxes that become an extra playspace, and even a curvaceous fake-turf-covered extension that is more like an extra hill in the garden.

For another Melbourne family, bringing an element of play into their extension design was about creating a more dynamic home environment. Cat Kohn and Gary Ford included a fully enclosed slide in the renovations to their Preston house, to help their daughter Elspeth and her friends feel that the built environment of the home was a fun place for them and not just an adult space. Quirky design features like the slide are “about quality of life, adding to the fun and memories created at home,” Gary says.

There are also plenty of opportunities to build creative playspaces around the home, with both built elements and plantings. For example, Gary and Cat designed their garden to attract insects and birds and encourage their daughter to explore and engage with the plants. And at Western Creek in northern Tasmania, Ann and Andrew Crowden’s three growing boys enjoy a fine example of that enduring backyard favourite, the cubby. Built by a friend from recycled materials and sitting atop an old tree stump, the cubby has bunks for sleepovers, a climbing frame, fireman’s pole and sandpit. The boys explain that they love having a space all their own, and Ann says that the cubby is “a great place for imaginative play and for the boys to be able to learn for themselves about trial and error, and risk. They’ve learnt a lot of things, such as that it may not be such a good idea to climb onto the roof.”

Playing for keeps

Along with a developing understanding of the importance of play, pressing considerations like climate change and the need to care for our environment influence playspace designers like Miriam in their work. “The importance of nature-based play in developing a love for our planet and inspiring its future custodians cannot be underestimated, and we feel a great sense of responsibility in creating gardens and playspaces that will provide lifelong memories of the beauty and importance of nature,” she says. Simon from Climbing Tree agrees. “As an educator, all I want to do is help children understand that we are not separate from nature, we are part of it,” he says, “and more kids playing more in nature may even shift how we value the environment and, ultimately, our planet.”

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

Energy efficiency front and centre: A renovation case study

Rather than starting again, this Melbourne couple opted for a comprehensive renovation of their well laid out but inefficient home, achieving huge energy savings and much improved comfort.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Pocket forests: Urban microforests gaining ground

Often no bigger than a tennis court, microforests punch above their weight for establishing cool urban microclimates, providing wildlife habitat and focusing community connection. Mara Ripani goes exploring.

Read more