Better together: exploring collaborative housing in Australia

From a couple of households to large ecovillages with a raft of shared facilities, collaborative housing projects come in many sizes and types, but they all offer the social, financial and environmental benefits of sharing resources and building community. We look at what’s involved in setting one up, and get advice from people around the country already doing it.

Ever had a hankering to live in a more connected community? You’re not alone. Interest in collaborative housing is rising in Australia. It’s shaking off its hippie image and becoming an increasingly relevant housing option as our population demographics change, households get smaller, and social isolation and housing affordability become serious issues. Many people are starting to look for something beyond the traditional living arrangement enshrined in the ‘great Australian dream’: a nuclear family in a detached house on its own suburban block.

“We have ended up losing the extended family setups we lived in years and years ago, and we are wanting to get that back,” says Caitlin McGee, a research director in housing futures at the Institute for Sustainable Futures (ISF) at the University of Technology Sydney. Initially researching the viability and benefits of collaborative housing for seniors, Caitlin and her colleagues expanded their scope to look at the subject more generally, including barriers to implementation and possible solutions. “Living in some form of collaborative housing can be beneficial at all stages of life,” she says. The ISF study led to the creation of the Collaborative Housing Guide, a free website that is an excellent resource for those interested in learning more about the subject (www.collaborativehousing.org.au).

Collaborative housing covers a very broad spectrum of housing arrangements, in a variety of sizes, for a range of ages and demographic groups, and with options for both owners and renters. There is a sometimes bewildering array of overlapping terms for collaborative housing projects: cohousing, co-living, cooperatives, intentional communities and ecovillages, to list a few. See the box below for an overview of different models.

No matter the model or particular name used, collaborative housing projects have a few common features. Broadly, there is a focus on sharing and building community. Specifically, they contain a mix of private and communal space, there is sharing of resources and equipment, and residents are more heavily involved in making their shared vision a reality. They might have input to design, financing strategy, development and ongoing management of the community post-occupancy – though the level of input and how things are run will vary from project to project.

What are the benefits?

Collaborative housing offers a variety of social, environmental and financial benefits.

Living as part of a connected community can help reduce isolation and improve wellbeing, and skills and assistance such as childminding and support for the elderly can be more easily shared. “The concept of intentional community is important to me,” says Mary-Faeth Chenery, part of the incorporated association behind WINC, a cohousing development for older women in Daylesford, Victoria, that’s currently in the design stages. “I want to know that I have good neighbours who will care whether I get up in the morning or not. And so many phenomenal ideas have come out of our group already – I’m looking forward to theatre productions and shared dinners and more.”

For Rhona D’Harra, at 82 the oldest resident at Denmark Cohousing in Western Australia (see ‘Building community’ in Sanctuary 48), being in touch with younger people is important. “There is so much delight in watching the children and young people who live here play,” she says. She also values the central garden, which provides a place for community residents to greet each other each day, even (from a suitable distance) during the coronavirus-related restrictions.

Many projects include design elements specifically to encourage incidental social interaction. For example, the WINC masterplan places car parking around the perimeter of the site rather than next to each unit. “You might walk past the common house and through the shared gardens to get to your front door,” says cooperative president Anneke Deutsch.

There are also benefits for resource use. Well-designed collaborative housing projects are able to use space more efficiently, as at The Paddock in Castlemaine where the housing density of the 26-home project is the same as in the centre of the town and yet fully two-thirds of the 1.4-hectare site is reserved for communal food gardens and bushland (see our article on one resident’s home at The Paddock on p28 for more). And beyond shared space, sharing facilities (such as laundries, guest rooms, home offices and workshops), equipment and even vehicles is resource-efficient, reducing the combined environmental footprint of the households.

Depending on how it’s set up, collaborative housing can also make buying or renting a home cheaper. Some projects are conceived entirely as social housing or include a proportion of homes for those who qualify – as in WINC. And opting for a smaller private space in return for access to the development’s communal facilities means some costs can be shared and individual household bills are likely to be lower. Furthermore, the developers’ margins and sales and marketing costs that are a feature of conventional speculative housing are taken out of the equation. Caitlin explains that some groups have even used a setup that means they pay taxes on land costs only, not the additional costs of development, because the ‘sale’ occurs at land acquisition. “While the details will depend on project specifics, apartments in collaborative housing projects can cost up to 25 per cent less to buy than similar apartments in the same locality,” she says.

A key feature of collaborative housing is that residents are actively engaged in the design and management of their community, and may also help to guide the development process, aided by a professional development manager. “This enables people concerned about the impacts of housing on society and the environment to promote sustainability outcomes,” explains Caitlin. “I see it as a holistic way of looking at housing. I’ve always been interested in both the environmental aspects and the social aspects of residential housing; collaborative housing brings the two together. By its nature it tends to have a lower environmental impact.”

Making it happen

If you think community living is for you, you might start by looking for a project near you that is already underway or complete, and investigate joining or buying in. If you are considering starting your own collaborative housing project, here are some broad considerations. You’ll find more detail in the Collaborative Housing Guide; it’s also a good idea to visit existing communities and talk to people who have already walked the path.

Gathering your community

At the heart of any collaborative housing project, big or small, is a group of people living together. This can be an extended family, a group of friends, or strangers who have come together because of a shared vision for how they’d like to live. Things to consider when forming your group include how many people you want to live with and where, whether you would like to live with people of a similar age and life stage to you or in an intergenerational community, and what values you’d like your future fellow residents to share.

Once you have the core of your group, an important step is to work out your shared vision and agree on how you will make decisions together. Mary-Faeth of WINC says that building group trust and having a good decision-making process are among the most important aspects of the collaborative housing journey. “If you don’t have trust and goodwill in the group you don’t have anything much.”

Brainstorming and creating a formal vision document is a good idea. The four friends behind Denmark Cohousing did this early in the process. “We had a very clear vision statement with an ‘imagined future’,” says Paul Llewellyn. “That was our only selection criterion for new members – read the vision statement and if you agreed and were willing to work towards it, then you were in and part of the journey to create an urban ecovillage.”

In Maleny, Queensland, not-for-profit Eco Villages Australia has developed a comprehensive 11-page ‘Founders’ vision’ document that can be adapted for each collaborative housing ‘village’ in its planned future network, to help group members distil their aims and values and communicate them easily to prospective members.

Next steps

Once you have found your group – or at least the initial core of it – and agreed on your aims, you’ll be faced with the practicalities of making your plan a reality. These include finding a suitable site, thinking through the ownership structure, working out financing for both land acquisition and for the design and construction, and finding and engaging professionals to design and build the homes.

Most of the groups we spoke to cautioned that it’s a long, often challenging road. “If you’re going to do it, it’s all-encompassing and you have to enter into it with a long-term commitment to creating something of value,” says Liam Wallis, director of ethical developer and sustainability consultant HIP V. HYPE. Liam and his family have just moved into their newly-completed townhouse, one of three that make up Davison Collaborative in Brunswick, Victoria; it’s an experimental project Liam and two good friends undertook to “test collaborative development on a manageable scale” and has a strong emphasis on sustainable design.

An early stumbling block can be local council zoning and planning conditions, which are often not readily adaptable to collaborative housing structures. Some very small projects – often involving extended families – take advantage of secondary dwelling allowances to turn single house blocks into a form of collaborative housing: see ‘Village green’ on p40 for one Canberra example.

Other projects are deliberately blazing the trail, engaging with councils to test new approaches to planning rules. Trish Macdonald, Ian Ross and Joss Haiblen are close to the development application stage of a small eco-cohousing project of three homes plus a common house on a large single block in a suburb of Canberra where medium density development is traditionally not allowed. They are part of the ACT government’s Demonstration Housing program, “testing innovative forms of housing not provided for under the current planning regime,” explains Joss. Their project involves a number of changes to the local planning regulations, which will apply only to their own block for the moment, but if the project is successful the idea is that the changes may be rolled out more broadly.

As for ownership structure, this is often dictated by financing options. “We found that the number one barrier for this kind of project is finance,” says Caitlin. “A lot of collaborative housing models originate in Europe, where there is often a different, more enabling financial landscape – especially lending to multiple parties is easier.” In Western Australia, Paul and his fellow founders established a not-for-profit, single-purpose company, Deco Living, to buy the land and build the ecovillage on behalf of resident investors. “Banks will talk to you when you are a company, because they understand the structure,” he says. “People wanting to join our community bought shares in the company to the full value of their future home. At the end of the build, the company simply bought back each resident’s shares in exchange for the strata title to their new home. The exchange gave rise to a newly formed Deco Housing strata company to operate and manage the ecovillage on behalf of all residents.”

Although there were only two households involved at the beginning, Ian, Joss and Trish in Canberra also formed a company to purchase their land and commission the design work. They planned to convert the company title to strata title when the build was complete, but discovered that this would be very expensive: “substantial stamp duty and other costs,” says Joss. Instead they will retain the company structure, meaning that residents are shareholders in the company; in the future if a party wants to move out, they will sell their shares in the company rather than the more standard selling of a strata title. “For small projects involving just a few households, the simplest way to go is generally to purchase and develop a strata title property as tenants in common using a co-borrower loan, along with a tailored legal co-ownership agreement,” says Caitlin.

At WINC, the group has decided on a strata title ownership structure after considering cooperatives and community land trusts (which are well-established in the US and the UK but not as well-known here) and not-for-profit companies. They wanted to use a familiar legal structure that would be easy to sell and borrow against. They have partnered with the not-for-profit Women’s Property Initiative, which will act as the developer for the project in return for retaining ownership of four of the homes to rent to women eligible for community housing. “It’s quite neat financially, and means we can house some of our members who can’t afford to buy in but meet the requirements for social housing,” says Anneke. She notes another difficulty for many of the older women who make up their group: “About a third of our members have some money but not enough to buy outright. And when you’re over 65, even if you’re only short a little, you can’t get a mortgage.” The group is lobbying government to extend the first home buyers’ scheme to people in this category, and coming up with other inventive ways to cover each other’s costs.

When you’re trailblazing, finding the right professionals is important. In Dunedin, 24-home High Street Cohousing, New Zealand’s first collaborative housing project designed to Passive House energy efficiency standards, is nearing completion. Tim Ross is involved as both future resident and architect, and says that their key problem was staying within the budget. “We were doing two brand new things for our area – cohousing and Passive House – and builders just didn’t know how to cost it, adding massive contingencies,” he explains. “Getting property valuers to recognise that the market would pay more for one of our houses than for a normal townhouse – important for securing the bank loan – was tough too.” They ended up bringing New Zealand’s biggest Passive House builder on board, who was able to guide the details of the design from an early stage and make more accurate cost predictions. “It’s very hard just to go out to tender with this kind of project when you’re on a budget,” says Tim. “It’s better to hunt down the members of your team specifically – find the people with the right expertise.”

Words of wisdom

Whether you are more drawn to a well-designed development with a few features to encourage a sense of community – such as a Nightingale building (see nightingalehousing.org), or The Cape ecovillage at Cape Paterson – or want to dive in and live in a community that shares much more, there will be a collaborative housing option for you, and it’s an exciting prospect. “We found through our research that there is a lot of enthusiasm about collaborative housing from stakeholders, including government,” says Caitlin, “but it’s still an emerging area in Australia, so there are a lot of things yet to be resolved.”

Despite the challenges, the consensus seems to be that it’s well worth it. “Each phase is challenging and rewarding and involves building community,” says Paul. “The gardens and trees are growing, and so are we.” Liam agrees: “Good things take time: that applies to buildings, gardens, and community.”

Collaborative housing models

These models describe some distinct types of collaborative housing and some approaches to delivering it, but they aren’t mutually exclusive. A number of these models may be combined in the one project. (Adapted from the Collaborative Housing Guide: www.collaborativehousing.org.au

Cohousing

Cohousing is one of the best-known models of collaborative housing. Since gaining popularity in northern Europe in the 1960s, cohousing has spread across Europe and North America, with a small number of projects also in Australia. Cohousing developments typically aim to create a sense of community and social belonging through a design that emphasises shared space and social interaction, and strong consensus processes around community governance.

Cooperative housing

Focused on the rental market, cooperative housing is a popular governance model for housing around the world. In Scandinavia, as much as 30 per cent of housing is cooperative housing, and in Australia there are already more than 8,000 people living in this type of housing. Cooperative housing providers use the cooperative law structure and apply it to housing; residents join the cooperative as members and rent from it. It is one of the best models for providing affordable, secure rental housing in a collaborative way, often for students and other lower-income groups.

Co-living

Co-living has been described as a 21st-century version of dormitory living for adults that helps to address urban housing affordability, while reducing resource use and supporting social connection. Typically developed under new-generation boarding house provisions, co-living provides rental accommodation in buildings that also include significant communal spaces. Some properties employ a dedicated community manager to help the community to thrive.

Building groups (Baugruppen)

Building groups involve a collective of prospective owner-occupiers coming together to co-create a development. They provide input to the design and may also get involved in putting together finance and overseeing development approval and construction. There are a number of ways this might occur, ranging from groups of friends coming together to develop, to strangers being brought together by an architect or development manager who is facilitating a development.

Small blocks

This is collaborative housing at the smallest scale – redevelopment of single-family dwellings or adjacent blocks to accommodate a small cluster of households, or redevelopment of small walk-up apartment buildings to increase shared facilities.

Collaborative retirement

The housing marketplace has many options that are aimed specifically at meeting the needs of older people. Many older people become interested in ‘downsizing’ after children leave home. Some may consider moving into a retirement village or another form of retirement living. Later in life, older people may come to need a higher level of aged care. Collaborative retirement is about applying the principles of collaborative housing to these options.

Intentional communities

Intentional community can be used as a broad label for many types of communities that have joined together to collectively create the place that they live in. In the Australian context, intentional communities would typically be thought of as located in rural or suburban fringe areas, and are generally larger – both in terms of land size and number of members – than other collaborative housing models. They typically have a shared vision and place a strong emphasis on sharing and communal living, and are often associated with pursuing a consciously devised social and cultural alternative to mainstream society.

Resources:

Collaborative Housing Guide: collaborativehousing.org.au

Cohousing Australia: communities.org.au

Cohousing New Zealand: cohousing.org.nz

Further reading

House profiles

House profiles

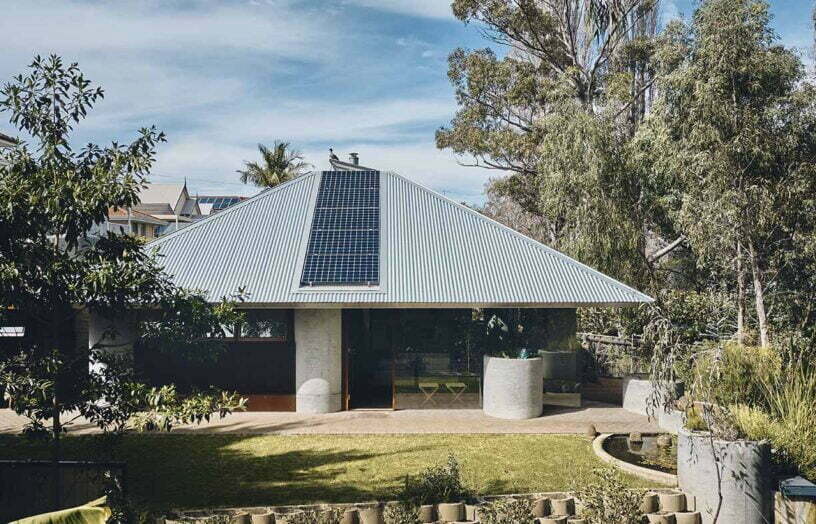

An alternative vision

This new house in Perth’s inner suburbs puts forward a fresh model of integrated sustainable living for a young family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Quiet achiever

Thick hempcrete walls contribute to the peace and warmth inside this lovely central Victorian home.

Read more