Ask our experts: Life cycle analysis

The Architects Declare Australia movement, launched last year in response to the growing climate emergency (see Sanctuary 49), now has nearly 900 signatories. One of the commitments is the inclusion of life cycle analysis to measure and reduce the carbon impact of design and construction projects; we asked Clinton Cole of Sydney’s CplusC Architectural Workshop to explain what his practice is doing to contribute to positive change in this area in alignment with their pledge.

A life cycle analysis (LCA) is the process of systematically calculating the environmental footprint of a product – in our industry, a building – over its entire life cycle, using software. It includes measuring the embodied energy in materials, the energy used to construct the building, the operational energy usage of the building throughout its life, and the energy use and environmental impact of building maintenance and end-of-life disposal of the components.

For designers, it isn’t always possible to predict how occupants of a building will choose to consume energy, or when and how the building will be demolished and what percentage will be recycled or sent to landfill, but we are able to accurately report on what specific materials will be used and how much of them. So, the most important component of the LCA of a building for architects and designers to consider is the embodied energy of the materials specified: the energy used to create and transport them. For example, the energy it takes to cut down a tree, machine the log, ship the timber to a distributor and transport it to the construction site is all tracked in the embodied energy of the end timber product.

The challenge architects have taking embodied energy into account when specifying materials is that information about the embodied energy in a product or the environmental impact of a particular material can be hard to find, and there’s no imperative to do so because it’s not a legislative requirement in the design process.

However, some manufacturers have Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) for their materials; these are independent scientific reports, breaking down in detail the environmental impacts of the product in terms of extraction of raw material, transporting it and processing it into the final product. Independent databases collate these EPDs, and LCA software translates this purely scientific data into usable systems for architects and building designers to start tracking the total environmental impact of the building, before it is even built.

We’ve started using LCA software on all our new projects, and on our recently built projects too to reflect on what we’ve been doing well and what we could be doing better. Using the LCA software in the design stage allows us to realise when a better material option is available, and what apparently small details actually have the biggest environmental impacts. For example, although they make up only a small part of the total material in a building, aluminium door and window frames are a killer to any project’s sustainability due to their very high embodied energy when compared to timber (not to mention the better thermal performance of timber frames, which reduces the operational energy needed to heat and cool the space.)

While researching different LCA software options, we found some to be lacking in detail and transparency – leaving the user uncertain whether the results are genuine – and others to be overly complex, failing to bridge the gap between pure science and real-world application. The software we chose, One Click LCA, works fluidly with the Building Information Modelling (BIM) software our office uses, is fully transparent in terms of product information sources, and is easy to navigate. It aggregates the most trusted independent research on embodied energy material data from all over the world on almost every conceivable material or product. If a product isn’t in One Click LCA’s database, all we need to do is send them the product’s EPD, and within 48 hours it will be added and shared globally with all other users. It even includes an average distance from supplier or source to the project’s location for transport energy calculations, and allows us to go to the next level of adding in estimated operational electricity and gas usage costs, solar, water storage, battery usage and so on.

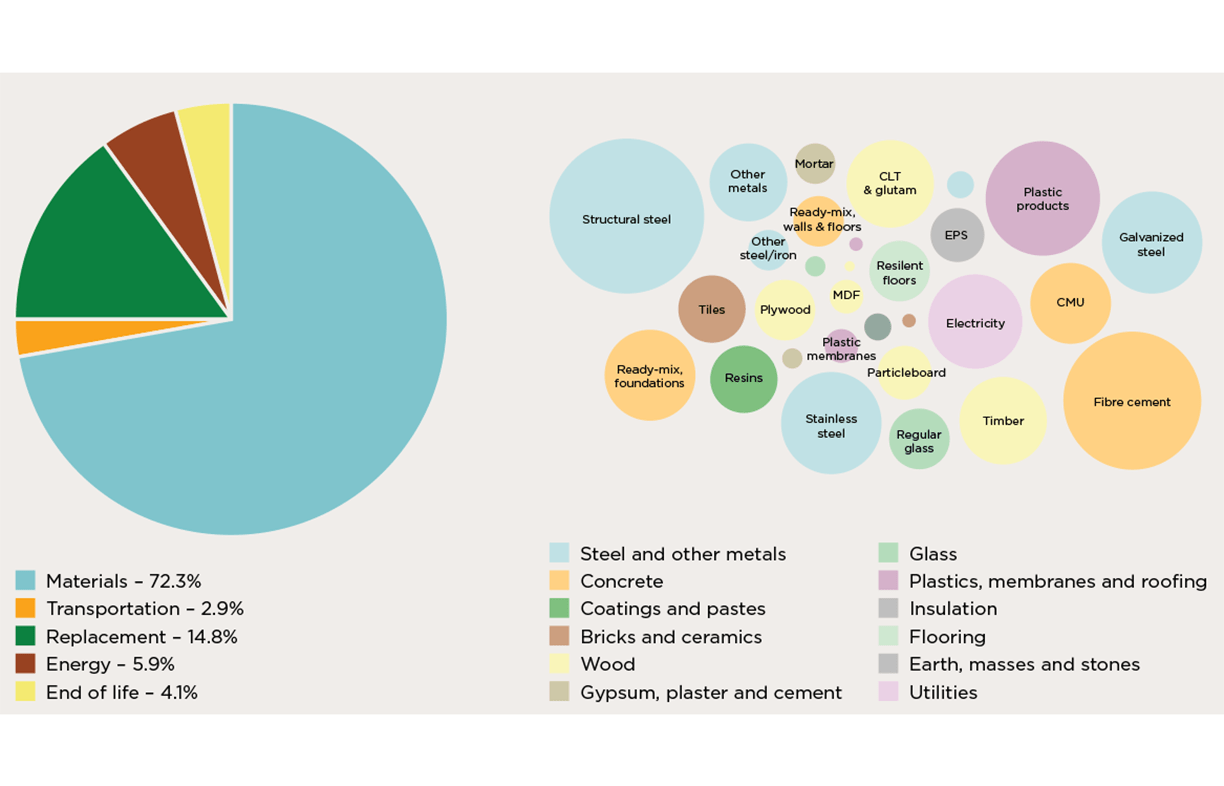

The first project we put through the software was my own recently completed home, our Welcome to the Jungle House. Despite being created three or four years ago, our BIM model integrated perfectly with the One Click software, allowing us to see the distribution of the environmental footprint across the life cycle. We knew at the design stage that with our 4.2 kilowatt solar PV system and 9.8 kilowatt-hour battery storage our energy bills would be low, but after inputting our real-world energy bills, we were surprised to learn that the operational energy of the building is estimated to be only 6 per cent of the total carbon emissions for the project over its lifetime (Figure 1). A huge 72 per cent of the footprint comes from the materials used, and by examining which building elements had the largest share of the environmental impact (Figure 2), we’re looking into how we can change our newer designs to create lower impact buildings.

In my view, this kind of software is the silver bullet that can change the world of architecture for the better and address the climate emergency. It is already used extensively in the USA and throughout Europe, but only two architecture firms in Australia are using this particular software, and only very recently. The LCA process will undoubtedly become a crucial stage in the design of all our projects, as the responsibility of architects to reduce the climate impact of our built environment continues to grow in these coming critical years. With greenwashing rife throughout our industry, being able to prove a building’s reduced environmental impact will be necessary to any firm that is serious about being part of the solution to the climate emergency.

My suggestion is that the Architects Declare movement should bring together the various Australian architect and building designer associations to lobby government to mandate BIM and LCA in all projects over a certain threshold, perhaps $500,000. I would like to see the LCA information and carbon impact of projects submitted for development approval made public by local authorities as part of the application process, for transparency. The next step would be mandated carbon offsets for a project’s life cycle carbon emissions.

If you are planning a build or a renovation, ask your architect or designer what they are doing to measure and reduce the impact of their projects – or make it an interview question if you are still choosing one. If your architect is using BIM software, there is no reason they can’t be doing life cycle assessments on your project during the design phase. It’s no longer acceptable to just turn a blind eye to these kinds of considerations in the building and design industry; it is the responsibility of every individual (both client and professional) to be doing the most that we can if we are to see a systemic change in the way we inhabit this planet.

LCA software like One Click is how all architects (along with professionals in many other industries) could manage and monitor projects, improve our projects during the design phase with respect to embodied energy, and show our clients in real time what the impact of every decision is on carbon emissions.

Further reading

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

Energy efficiency front and centre: A renovation case study

Rather than starting again, this Melbourne couple opted for a comprehensive renovation of their well laid out but inefficient home, achieving huge energy savings and much improved comfort.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Pocket forests: Urban microforests gaining ground

Often no bigger than a tennis court, microforests punch above their weight for establishing cool urban microclimates, providing wildlife habitat and focusing community connection. Mara Ripani goes exploring.

Read more