Are we aiming for the stars?

Two decades after the introduction of the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme, an analysis looks at how we’re building, the Star ratings we’re achieving and what needs to change to deliver climate resilient homes.

As regular Sanctuary readers will know, in most states in Australia we rate the design of housing for energy efficiency on a scale of 0 (worst) to 10 (best) Stars via the Nationwide House Energy Rating Scheme (NatHERS). The NatHERS rating is based primarily upon energy required for heating and cooling and is adjusted for local climatic conditions. Theoretically, at 10 Stars houses should require no mechanical heating or cooling to maintain year-round thermal comfort.

The current regulatory minimum for newly built homes is 6 Stars. But there is plenty of evidence that we need to be building to 7.5 to 8 Stars in many climate zones to deliver optimal environmental, social and economic benefits for households and broader society.

In Australia our minimum standard is already more than two NatHERS Stars behind comparable developed countries. Research in 2018 by the Australian Sustainable Built Environment Council and ClimateWorks Australia calculated that sticking with our current 6 Star minimum (rather than raising it to 7.5 Stars) will result in an estimated $1.1 billion in avoidable household energy bills and an additional 3 million tonnes of greenhouse gas emissions between 2019 and 2022 (bit.ly/2SdGjFx).

We can build to a higher performance standard: Sanctuary is full of houses that rate at 7.5 Stars or above. And the good news is that many performance improvements can be achieved for little, if any, additional capital cost (bit.ly/2XzIfOx). [Ed note: NatHERS ratings assess a house as designed. For analysis, this article assumes the design rating is a proxy for as-built performance; in fact this may not always be the case.]

What performance standard are we building to?

The argument is often made by the building industry and policy makers that the market will sort it out – that if householders value higher performance homes, they will demand them and they will be built. But what does the data show, after several years of a 6 Star minimum?

CSIRO’s new Australian Housing Data portal (ahd.csiro.au) has given us the ability to look at energy ratings issued across Australia. Making the most of this, our team from RMIT University, CSIRO and the University of South Australia recently examined 187,000 energy rating certificates issued for new homes in South Australia, Australian Capital Territory, Western Australia, Victoria and Tasmania from 2016 to 2018. (We excluded New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory as they have different requirements for minimum building energy performance.)

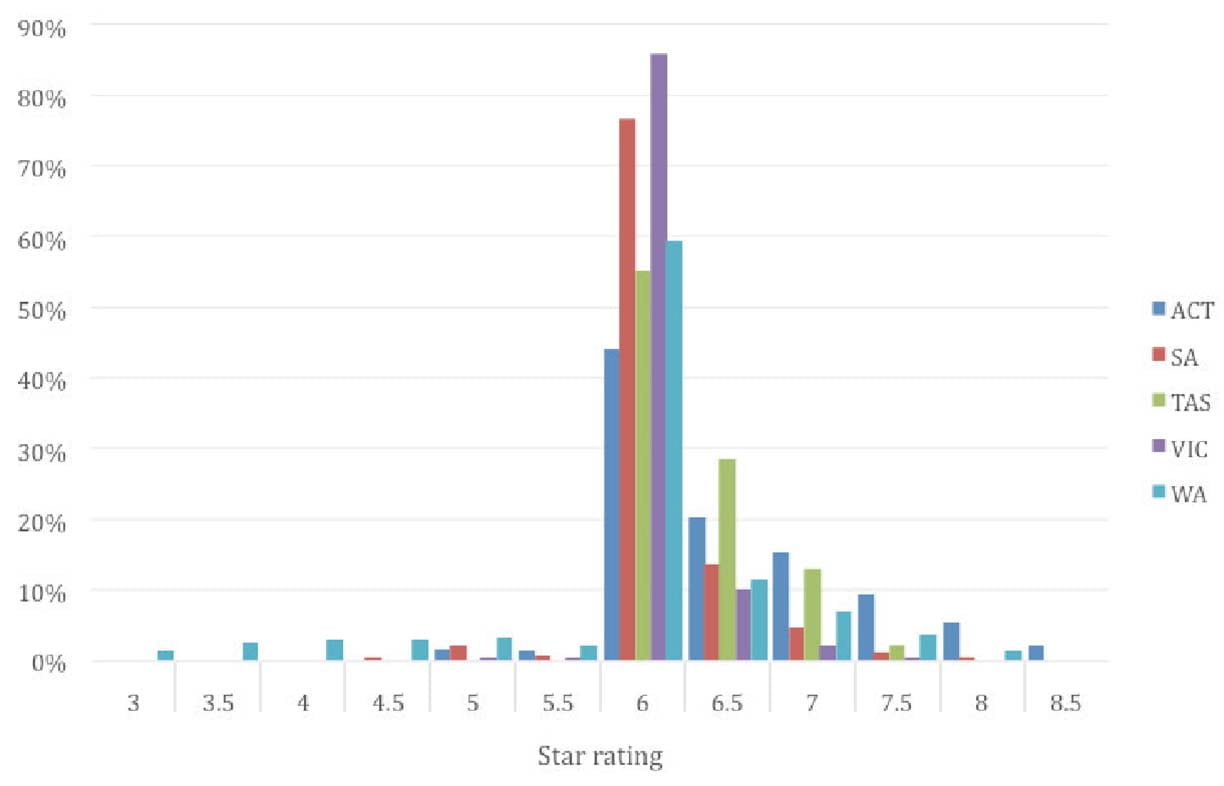

Here’s what we found: most homes only meet the minimum legislated standard for thermal comfort of 6 Stars. In other words, most people are getting the lowest performing houses that our National Construction Code (NCC) allows. According to our data, 82% of new homes from 2016 to 2018 were built to the 6 Star standard. And only 1.5% were designed to perform at or above the optimal 7.5 Stars.

Is this the same everywhere?

There are differences across the states and territories (see Figure 1). The worst performers were Victoria (86% of new houses at 6 Stars), followed by SA (80%) and WA (75%). Some jurisdictions are doing a little better. In the cooler climates there were more homes designed to 7 Stars and above (ACT 33% and Tasmania 15%). In fact, in the ACT 8% of homes were at 8 Stars or above. Still, even in these locations, the large majority were only meeting the minimum.

Of concern is that there was also a small percentage (around 2%) of new dwellings not meeting the 6 Star requirement. In WA the percentage of dwellings below 6 Stars was a large 16%, followed by South Australia at 3.4%. It is unclear why this is the case, but it may be explained by new dwellings using pathways other than NatHERS to show compliance with the energy efficiency provisions of the NCC.

The average Star rating across all the data was 6.2 Stars, a figure that did not change over the three years studied (see Table 1). However, the data did show that in the ACT standards improved, with the average Star rating for new houses there rising from 6.5 in 2016 to 6.9 in 2018.

| State | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Victoria | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| South Australia | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Western Australia | 6.3 | 6.1 | 6 |

| Tasmania | 6.4 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| ACT | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.9 |

| Average across all data | 6.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

Table 1: Average NatHERS Star rating for each state for 2016 to 2018.

The ACT is an interesting case, boasting the highest average rating among the regions studied at 6.9 Stars and outperforming fellow cool climate location Tasmania, suggesting that there must be other mechanisms at play in our capital territory. Notably, it’s the only region in Australia with mandatory disclosure of a house’s energy rating on sale or lease. The intent of mandatory disclosure is to provide consumers with more information on expected thermal performance and energy use, to help with their decision making. The data suggests that consumers are gradually influencing the housing market in the ACT to deliver higher performance outcomes; mandatory reporting could be a part of that.

The case for increasing minimum standards

Policy makers and the building industry have traditionally been hesitant to change minimum performance requirements, saying that consumers will demand improved performance if it’s valued. While we need housing purchasers to do this, and it may in time help influence the market to deliver improved housing performance, the evidence shows that this is not enough. The data we looked at indicates that even years after the introduction of the 6 Star minimum standard for energy efficiency, the majority of the building industry still delivers to minimum requirements only. Whether through lack of sufficient knowledge about the energy performance of their homes, the hurdle of perceived extra upfront costs or other factors, consumers are not demanding the better performance that would not only improve the liveability of their home but also maximise their economic outcomes. This means that relying on consumers to create a shift to higher performance outcomes may be unrealistic.

If we are to make progress towards a zero carbon housing sector by 2050 (in line with global greenhouse gas emission reduction targets), we should be delivering housing performing to 7.5 Stars or beyond right now. The data we looked at indicates that the minimum regulatory standards are a powerful tool to push the market and suggests that only a significant increase in the minimum Star rating will achieve this outcome in the short term.

Any changes to minimum standards should also consider the opportunity for a more holistic house energy or carbon rating including elements not currently within the rating scheme – such as appliances, renewable energy generation and battery storage. As our homes and available technology continue to evolve, we must make sure that building codes and minimum requirements factor these changes in.

The next opportunity for increasing the minimum Star rating will be in 2022 as part of the next round of updates to the National Construction Code. Significant changes must be made. While we can all demand improved performance outcomes in our houses, we must also continue to push for improved minimum regulations to support change to industry practices.

Get on board

As part of a national coalition of community organisations, Sanctuary’s publisher Renew is actively campaigning for an increase to the minimum energy efficiency standards.

Read more and support our Climate Resilient Homes campaign: renew.org.au/donate/crh

About the authors

Dr Trivess Moore is a lecturer in the Sustainable Building Innovation Laboratory at RMIT University. Dr Stephen Berry is a building energy scientist at the Barbara Hardy Institute, UniSA. Michael Ambrose is a senior experimental scientist at CSIRO focusing on residential energy efficiency. Access their full report ‘Aiming for mediocrity: The case of Australian housing thermal performance’: bit.ly/2YFzK0Y

Further reading:

Ideas & Advice

Ideas & Advice

Energy efficiency front and centre: A renovation case study

Rather than starting again, this Melbourne couple opted for a comprehensive renovation of their well laid out but inefficient home, achieving huge energy savings and much improved comfort.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Pocket forests: Urban microforests gaining ground

Often no bigger than a tennis court, microforests punch above their weight for establishing cool urban microclimates, providing wildlife habitat and focusing community connection. Mara Ripani goes exploring.

Read more