The right to roam

Forage-friendly landscapes are everywhere in Australia, including in the suburbs. But before you go out and fill your basket, familiarise yourself with the rules of engagement, writes Kirsten Bradley of Milkwood.

The food is all around us. It’s under our feet, along the path edges and next to the highway. It’s in the sand dunes, all over our favourite park and down nearly every back lane. There’s food out the back of the doctor’s surgery, hanging over the fence. It’s even between the cracks in the bricks of our patio. We just need to learn how to see it.

Foraging for weeds, wild food and feral fruit is a simple art and a pleasure that’s available to absolutely anyone. You don’t need a backyard, or a garden, or a farm – you can live in a high-rise apartment and still become a competent forager.

All we need is a willingness to learn, good information and the eyes to see.

Foraging connects us with the world, and with each other, in many different ways. Pattern recognition takes up a large part of the human brain. Traditionally, learning and knowing the patterns of which leaves and berries to eat and which ones to leave alone was central to life (quite literally).

Once you know what you’re doing, thanks to our capacity for recognising and remembering patterns, telling the difference between nettle and fat hen, or spotting a plum tree at a distance becomes as obvious as looking at a tomato.

That is clearly a tomato, we think. I know it has no poisonous close look-alikes, so I can happily eat this tomato without asking or checking with anyone, for I know that it is a tomato. It’s the same with foraging, once you get the hang of it.

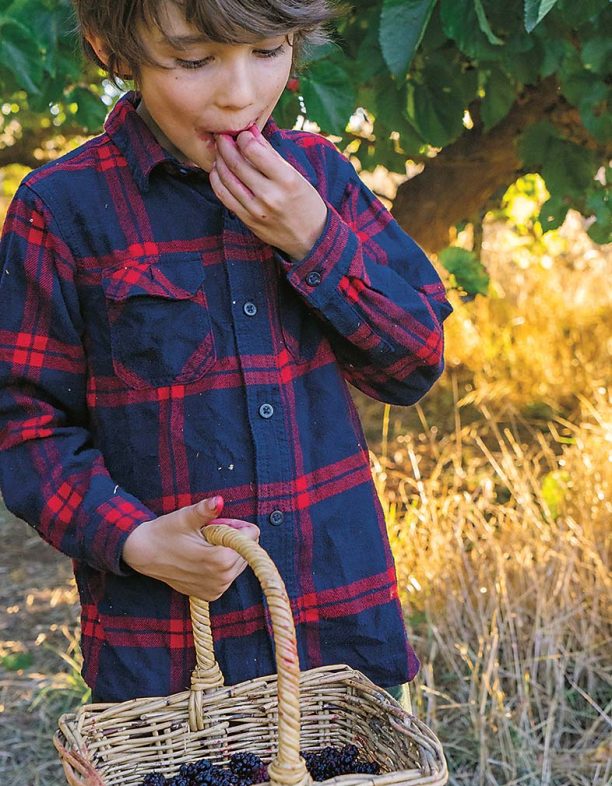

Children are pattern engines of the most focused kind: this is different from that; this goes with this one, not with that one. As parents and carers, we have a huge influence on what patterns children learn from an early age. Foraging as a family gives kids the chance to use their clear-eyed abilities for pattern recognition to build life-long skills – this is a nettle; that is a dock leaf; that tree is a plum, this one is not.

These skills will help nourish them in a very different way to learning the faces of Thomas the Tank Engine and all his friends. Take your kids with you when you go foraging and learn to see your local ’hood differently, together.

My family spent many summers in the back gullies of the Lithgow valley, where my mum was raised. Ruins of old shacks and houses from the early coalmining days are everywhere, now slowly being reclaimed by the Australian bush. These gullies were, and still are, peppered with feral fruit trees of European origin, both old and new. Some mark where a small home once stood and some are the result of birds dropping seeds.

The bounty of these gullies can be immense, so each summer and autumn we’d load up the car with buckets, baskets and bags, and go out hunting. We had staked out the trees by noticing their blossoms in the spring, as Mum knew (mostly) by the flowers which were apples, plums, pears and all the rest. We’d make a note and then check back in late summer.

Sometimes the harvest was small and sometimes it was huge. Pears and nectarines and apples for days – so much preserving! It was free feral fruiting, a family exercise that meant we spent a bunch of time helping and talking to each other as we picked.

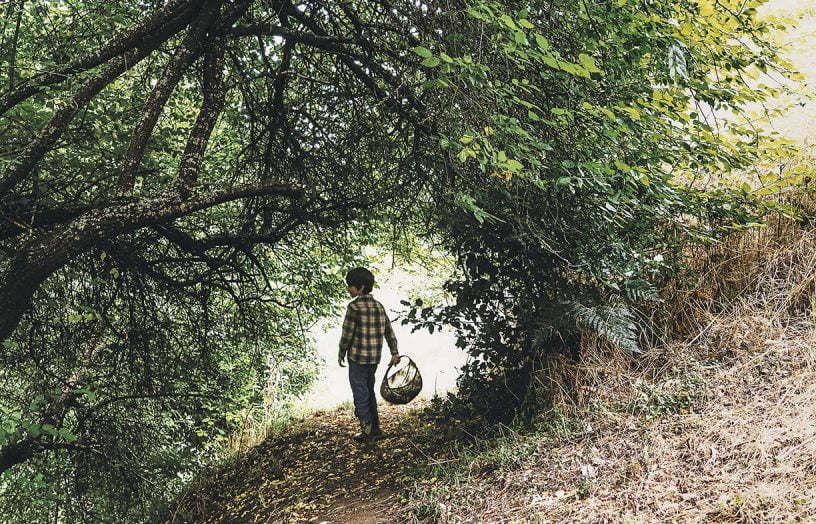

Foraging around where you live, or in a place that you visit often, also embeds you in a place like few other activities can. A map grows in your head of your local park, gully, headland or railway easement, with points of reference that are different from how you would usually see the local environment.

The patch of wild fennel, the boggy ground where the dock grows, the salty soak where there’s always some samphire, that plum tree down near the bridge by the railway that fruits just before midsummer. It’s a map of belonging, drawn with lines of food, seasonality and small discoveries of knowledge, collected over time.

Foraging also connects our palates with our local terroir like few other foods we have access to. It allows us to source local, seasonal food with minimal food miles and removes many of the unknowns about how that food was produced. We know what we’re eating and what it took to get these greens, these apples, this fennel from where they grew and into our kitchen. And that is a very good thing.

So foraging is the story of us, as a people, as a species. Long before we cultivated land and kept animals, we foraged. And still, up until the last few generations, we continued to forage, regardless of what was growing in our fields, because wild food is always different and it’s vital. Different soil, different nutrients, different medicine – all good things to bring into our homes.

Our ancestors knew this, and we can learn to remember.

The right to roam (or not)

In some countries the importance of foraging and therefore the rights for all to forage are enshrined in law. Sweden has Allemansrätten – the right of public access – which allows anyone to collect wild food and flowers from the forest (excluding any protected species), regardless of who technically owns that forest. Scotland has the ‘right to roam’ law, which allows anyone to use land, public or private, for recreation or to gather wild foods for personal use. Both laws require foragers to not destroy or disrupt any vegetation in the process.

In some other countries, the laws are the opposite. It depends where you live, as well as where and what you’re hunting for. Sometimes it’s considered trespassing, sometimes it’s not.

And then there are all the other spaces – the nectarine tree growing by the railway siding, the dandelion in the spare lot by the bus stop, the fruit trees down the gully, the fennel by the highway. Use your head and your common sense. Be safe, be careful and find out what you need to know about where you want to look.

Always keep your eyes sharp for new plants, wherever you are. You’ll be amazed at what you’ll find.

Basic foraging guidelines

No matter what you’re gathering and where you’re gathering it from, ethical foraging comes with certain responsibilities and considerations.

Always leave the first one you see

Whether it’s a dandelion, seaweed or a branch of wild plums, never take the first one you see – just in case it is also the last one.

This is a great first rule for mindful foraging – it kickstarts your restraint from the beginning, right when you’re super excited to have finally found what you seek. Go easy, go slow and be aware. The gifts of the wild are there for all – you, the other animals, and the other foragers, too.

Harvest leaf and fruit, not the whole plant

Being careful not to damage the plant you’re foraging from is paramount. This ensures it’s a resource for those who come after you, as well as ensuring that the plant continues to be healthy for whatever purpose it’s growing there.

Observe and interact

As well as being a core permaculture principle, ‘observe and interact’ is good advice for foragers. Do you definitely know what species it is? Does the plant look healthy? Is it in an area that’s likely to be sprayed by the council? If urban, is it in a heavy foot traffic and dog-walking (and therefore dog-pooing) area? These are all good questions to ask.

Consider the inputs around the plant

Many councils spray their roadside and parkland weeds and unwanted plants with herbicides to control their growth, despite the damage these chemicals do to many parts of the ecosystem. You can usually find out where and when this has occurred from your local council, and it’s a good thing to consider before you go foraging. Streams are also worth looking into – if there’s heavy industry upstream, which might contribute to significant heavy metal loadings in vegetation, it’s best not to eat the greens that you find there.

Likewise, in country areas, try to find out what went on in the past. Most times it will be completely fine, but occasionally it won’t be. We once found a great crop of nettles down by the woolshed and were happily eating them until someone mentioned that was right where the old sheep dip used to be, where the sheep were dunked in chemicals twice a year, meaning a very nasty toxin loading in the soil around that area. We stopped eating them and found another good patch of nettles in an open paddock up the hill.

As wild food lovers, we’re happy to take our educated chances on eating what we find – you soon get to know what kind of areas are likely to be clean. The alternative is often eating fruit and vegetables that have been grown far away and had questionable inputs applied during growing or harvesting to prevent spoilage. We’ll take the weeds and random feral fruit, thanks!

Public versus private land

Going into someone’s yard or farm to pick fruit or anything else without asking is not okay, of course. But a fruit tree branch overhanging a public laneway is generally considered (by us and many others) to be fair game. Public parks and gullies offer little problems for foraging, as do headlands, public reserves and roadsides.

The art of asking

If you’ve found an amazing lemon, apple or persimmon tree that’s technically on someone’s block but seems to not be being picked, go and ask if you may. You’ll be surprised how often you get permission. A big jar of home-made jam or preserves, returned to the owner, often seals the deal for next year’s access – be brave!

Sometimes it’s a case of being prepared to ask forgiveness rather than permission, such as in the case of crown land, like in the gullies of Lithgow. Or at an abandoned farmhouse that has a beautiful big mulberry tree alongside, with no one around to ask permission. If you’re respectful in your attitude and in your harvesting, leaving everything as it was except for the fruit now in your basket, sometimes that’s the best you can do.

If in doubt, go without

For fruits like apples and plums, there may be little doubt with identification – we’re so familiar with these plants from the supermarket, media and our own backyards. However, for some wild plants and fungi, the forms of branch, leaf, fruit and berry may not be so recognisable.

If you find something that you ‘think you’ve been told is edible but can’t remember if this is the one’, it’s a good idea to pick a bit, take it home (uneaten) and do your research with the plant or fruit beside you. If you were right, oh, happy day. If you were wrong, it’s just as happy a day that you didn’t eat it.

There are some great pocket reference guides for weeds and wild food, so find one that covers the species you’re likely to find. If you live in Australia, take particular note that many of our indigenous fungi are not well researched when it comes to edibility. Species can look like a common edible European mushroom when they are not. Go gently, take care, observe, test, confirm, and only then, taste.

Only take what you need

If the plum tree you’ve found down the gully is full of ripe plums, it doesn’t mean you need to harvest 12 buckets if you will, in fact, only use three. Harvest three buckets instead and tell your friends where the tree is. Consider also that you may not be the only forager of this tree.

Resources held in common good on common ground should be treated as just that – a common resource, not just for you. Leaving plums on the tree is not wasting them. It’s allowing for other possibilities, outside your small reckoning. Use what you harvest and use every bit. This is gratitude, and ethical foraging.

This is an extract from the ‘wild food’ chapter of Milkwood: Real skills for down-to-earth living. Authors Kirsten Bradley and Nick Ritar, published by Murdoch Books. RRP $45.00. Photography by Kate Berry and Kirsten Bradley; illustrations by Brenna Quinlan.

Further reading:

Outdoors

Outdoors

Gardens to go

Jacqui Hagen is a keen gardener who has transformed the gardens of numerous rental properties across Melbourne. She shares some tips and tricks for bringing your garden with you when it’s time to move.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Pocket forests: Urban microforests gaining ground

Often no bigger than a tennis court, microforests punch above their weight for establishing cool urban microclimates, providing wildlife habitat and focusing community connection. Mara Ripani goes exploring.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Nourished by nature: Garden design for mental health and wellbeing

There’s plenty of evidence that connection with nature is beneficial for both mind and body. We speak to the experts about designing gardens for improved mood and wellbeing, and what we can do at home to create green spaces that give back in a therapeutic way.

Read more