A greener festival

Music festivals are a growing part of Australian culture, but how do we make sure these parties have a positive impact on the planet? Sophie Weiner looks at how to create a more sustainable festival scene.

Australian music festivals often seem to present a worst-case scenario for sustainability. The massive amount of waste generated by the festival circuit can really put a damper on the party experience for anyone who cares about protecting the environment.

Research released by the advocacy group Green Music Australia earlier this year from a survey of 800 attendees at Falls Festival, Party in the Paddock and Unify Gathering found some sobering figures. One-third of festivalgoers surveyed considered their tents single-use items, while 50% believed that the waste they were generating somehow didn’t go to landfill. The disheartening research also found that 55% of attendees didn’t believe they were responsible for cleaning up after themselves.

This can seem a bleak landscape for those who care about both live music and sustainability. But the environmental impact of festivals is too important to ignore. The festival industry has experienced unprecedented growth around the world in recent years. A 2018 report from consulting firm PwC found that the global live music industry will be worth $31 billion by 2022. In Australia alone, industry group Live Performance Australia found record-breaking attendances at live music events in 2017, with 23 million attendances at a live music event of some kind and those events generating $1.88 billion in ticket sales. Festivals were among the categories of events that experienced the greatest growth. And an Eventbrite survey found in 2018 that respondents attended two to three festivals a year, with 40% saying they’ve travelled to another state for a festival, and 16% reporting travelling overseas.

Transforming festivals from celebrations of excess to sustainability is not an easy feat. It can be hard enough implementing sustainable practices in your own home—encouraging tens of thousands of partiers living together for just a few days to do the right thing can feel impossible. But though the problem can seem overwhelming, there are fans, organisations, promoters and musicians working to implement change at every level and in every area of the festival scene. The culture is changing, albeit unevenly, and there are a variety of innovative projects underway to green the festival scene.

Greening the scene

Several organisations are spearheading a sustainable movement for the festival circuit. Green Music Australia uses music and musicians to push for a greener world, including issues with music festivals, while international organisation A Greener Festival directly targets festivals by using research and advocacy to bring events on board with better sustainable practices.

According to A Greener Festival’s Australian representative Amie Green, the growth of the festival industry isn’t all bad—it has also led to a greater diversity of available events, including those that explicitly market themselves as sustainable, allowing attendees to vote with their wallets.

“Since there is such a plethora of events to choose from, having the green edge brings in more ticket sales,” says Amie.

A Greener Festival, like Green Music, has led the way in creating infrastructure that encourages sustainable practices at events. Born out of university research in the UK in 2005, the group has pushed for change through recruiting major festivals to the cause. They assess nearly 50 participating festivals on vectors of waste, emissions and more, and host an awards ceremony to celebrate the events that perform well.

Amie says she has seen growing interest in sustainability from festivals around the world in recent years. To that end, A Greener Festival leads sustainability training for events professionals, producing a group of 250 certified assessors who can quantify how festivals are performing in relation to sustainability goals.

Festival sustainability issues are a complex problem and a multifaceted approach is necessary. To meet this challenge, the festivals that are working to improve their sustainability must use a variety of tactics.

What about waste?

A pile of garbage can’t be easily ignored, so it’s not surprising that eco-friendly festivals often tackle waste first. Even ignoring the blasé attitude of some festivalgoers, the problem is challenging. Many camping festivals are held on greenfield sites far from a metro area. To capture recyclables in these areas often requires trucking them for hours to the nearest plant, reducing the emissions benefit.

But there are things that can be done. Victorian festival Folk Rhythm and Life, known for its focus on sustainability, managed to make the transition away from single-use plastic cups years before the current focus on greening the festival circuit, while the UK’s Glastonbury Festival recently banned single-use plastic water bottles. Rainbow Serpent, held in western Victoria, is known for its participatory daily clean-up sessions, and introduced washable crockery in 2018.

Groups like A Greener Festival and Green Music Australia are looking for ways to address the problem of single-use camping gear as well, by holding roundtables with festival organisers and promoting the benefits of investing in decent camping gear. Many festivals, like New South Wales’s Strawberry Fields, now offer ‘pitched tent’ options for attendees who don’t want to bring their own camping gear, which can also appeal to those who are taking buses or carpooling to a site.

One of the best examples of incorporating sustainable waste practices into a camping festival comes from Woodford Folk Festival, the long-running week-long event in Queensland. Woodfordia, as the land the festival is held on is known, recently committed to using biodegradable crockery and cutlery at their food stalls and eliminating all single-use plastic. Because the festival also owns the land where their event takes place, they are able to compost all of the biodegradable waste produced on-site, which is then used in their yearly tree planting event.

It’s even possible for festivals to have a lasting positive impact on their venues or sites by pushing for change, says Sustainable Living Festival director Luke Taylor.

“When we started at Federation Square in Melbourne there was no waste separation happening,” he says. “Over the course of working with Fed Square we’ve helped them to change their own processing, and now they have four streams for waste.”

From the bottom up

Over the last 10 years, composting toilets have become a go-to way to reduce both waste and emissions at festivals. Folk Rhythm and Life founder Hamish Skermer started a company, Natural Event, that has become one of Australia’s biggest providers of composting toilets for events. With the cheeky slogan “Changing the world from the bottom up”, Hamish has found a way to scale composting toilets so they can work at both international events like Glastonbury and festivals closer to home, like Meredith Music Festival. The toilets eliminate the need for trucking sewage, and ultimately provide valuable compost to local farms.

Woodford Folk Festival has gone another way with their sewage—since they own the land, the festival organisers have been able to establish real infrastructure on the former dairy farm, including a sewage treatment plant specially designed to deal with the variable demand that comes from hosting a 120,000-person event one week of the year.

Woodford general manager Amanda Jackes acknowledges that having your own land can make addressing sustainability easier.

“When someone is coming into a greenfields site that’s owned by the government or an external party, there are limitations on what you can do. It is a lot harder,” she says.

Amie says she’d like to see more innovations like greywater used at festivals, which often occur in drought-stricken areas, but acknowledges that the level of local knowledge in remote areas can be a problem, especially when it comes to council approval. But there are solutions for that, too. At a Melbourne Music Week panel on sustainability in November, Hamish recounted shaming a rural council with their own environmental statement in a bid to get his composting toilets approved. It worked, and the festival used the toilets.

Getting there

Transport can be a tricky piece of the festival sustainability puzzle. For city centre events, it’s easy to push the use of public transport, but many festivals are held in remote locations away from public transport networks and require bringing bulky camping gear. Sustainability advocates have used several methods to cut down on the number of vehicles travelling to these events.

Charging for vehicle passes is one proven method to encourage carpooling, but many festivals also provide bus services from major cities. According to Strawberry Fields organiser Tara Benney, 4000 people travelled to the festival on the border of Victoria and NSW by bus this year, out of 8000 or so total festivalgoers. The festival encourages this by subsidising bus tickets, which cost only $20 each way from Melbourne or Sydney. Taking a bus or carpooling also reduces the amount of stuff that attendees can bring with them, reducing waste at the end of the event. Strawberry Fields offsets its transport emissions with TreeCreds carbon credits, making the festival’s transport carbon-neutral.

Woodford Folk Festival also encourages attendees away from cars by providing buses from Brisbane and to meet local trains, while a Brisbane bike shop makes biking to the festival possible by allowing attendees to drop their gear at the shop and driving it in a truck to the festival, where attendees can claim it when they arrive.

International performers who must fly to festivals is another can of worms, and it’s hard to imagine the festival scene eliminating the big-name acts that draw their crowds. But many festivals, including Melbourne Music Week, are beginning to buy carbon offsets to compensate for flight emissions.

Festival efficiency

Energy efficiency can often be sidelined in conversations about green events. But some, like the Sustainable Living Festival, which takes place across dozens of venues in Melbourne over the course of a month, have made green energy a focus.

“Twenty years ago, to be in an event venue that was powered by renewables was unheard of,” Luke said. “But now there are many event venues that are using GreenPower or even generating their own power. That’s a major shift.”

Some festivals have even taken the step of going off-grid, producing their energy via solar power on-site. Helsinki’s Sunplugged, produced by Finnish energy company Väre in April 2019, was powered by a combination of solar and kinetic energy from energy-generating bikes. From 2016 to 2018 a group of musicians in Los Angeles ran Sunstock Solar Festival, an all-ages, zero-waste solar-powered event.

“It’s so nice not to have loud gas generators chugging away and blowing smoke into the event space, messing up the vibe,” Skylar Funk, a founder of Sunstock, told the Los Angeles Daily News in 2017. “Clean, quiet and free solar energy excites me.”

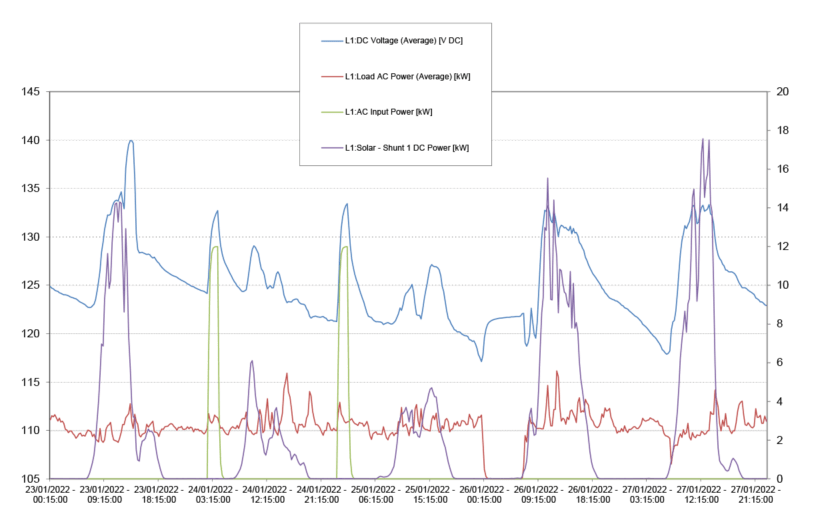

If festivals like these are to become more common, event producers will need access to affordable solar systems. In the UK, Firefly Hybrid Power rents hybrid generators to events, where they can be run with diesel or connected to wind or solar power. But even without a renewable power source, using a generator with a battery can greatly reduce fuel usage.

“When Chemical Brothers is going nuts and the sound and lights are up, that’s a peak energy use. Then the second after they finish playing, the use goes way down,” Hamish said at the panel. “But festivals don’t turn the generator down. Firefly has created a festival network where non-peak power goes into the batteries so it can be drawn on as well. It’s reducing diesel use.”

Plus, with the help of a company like Firefly, the generators can be rented, meaning their upfront cost is shared by the company.

Even without these kinds of services, festivals which run off renewable energy are beginning to happen in Australia. Woodford Folk Festival says it intends to get off the grid with a combination of batteries and solar starting next year.

Reducing carbon

Amie says that, in recent years, the requests that A Greener Festival receives from festivals who want carbon analysis has exploded. But reducing carbon can be a complex endeavour. Melbourne Music Week has been carbon neutral certified for the past two years.

Paul Whelan, who works for the City of Melbourne and was involved in Melbourne Music Week’s sustainability goals, says he dug down into the data to find where they could cut carbon emissions from the operation. He found that food was the second biggest source of emissions after travel. This year, the festival decided to reduce the amount of red meat served in catering.

“We can’t control how people get here, but we could impact those emissions,” Paul said at the Melbourne Music Week panel.

Woodford Folk Festival’s strategy for reducing carbon emissions goes hand-in-hand with their stewardship of their land. In 1995 they began holding a yearly event called The Planting, where members of their community planted 10,000 native trees and plants on the property. They’ve continued to plant thousands of trees a year ever since, growing an entire forest where none existed before.

Changing the culture

In conversations about greener festivals, organisers often complain about the hedonistic culture that they feel is endemic to the scene and prevents much of their work from taking hold.

“With music there’s this dichotomy. We have everyone’s attention, because everybody loves music,” Tara said at the panel. ”But it’s also associated with partying. And partying, especially in Australia, is associated with a ‘f*ck it’ attitude.”

To truly change festival culture, these organisers say, we need to change attitudes. Festivalgoers need to respect the land and their fellow attendees, or even the best systems will fail.

Organisers agree that providing services is not enough—they need to provide education as well.

“I’m sure there are many people who come to the festival who have never used a composting toilet before,” Tara said. She believes that education enables guests to gain an understanding of why sustainability matters in the outside world as well. “It’s not just about giving them the toilet, it’s about giving them a tool kit that they can take back to their own lives.”

Some of the organisers do this very intentionally: by offering talks on sustainability, like Melbourne Music Week, by educating attendees about the land the festival is on, as in the nature walks and eco-talks run by Woodford, by introducing attendees to new renewable technologies, like Sunplugged, or by instilling a sense of collective responsibility for the land and each other, as festivals like Folk Rhythm and Life have done from the beginning.

There’s a long road to truly green festivals, especially in the mainstream. But producers remain hopeful about the potential of events to open attendees’ eyes to a new way of seeing the world.

“There’s an enormous potential in festivals as a place where people break from day-to-day life to reassess the stories that shape their lives and the society we exist in,” says Berish Bilander, CEO of Green Music Australia, who was also at the Melbourne Music Week panel. “Festivals can at least offer us a glimpse into a [more sustainable] world and help us ask questions and find solutions that we can take back into our lives.”

A Greener Festival: agreenerfestival.com

Green Music Australia: greenmusic.org.au

Natural Event: naturalevent.com.au

Further reading

Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Preparing homes and towns for floods

For those in flood-prone areas, preparing your home for a flood isn’t just smart; it’s essential. Without it, recovering from flood damage can be slow and difficult. But with the right retrofits, and an understanding of flood policy and insurance in Australia, damage can be minimised, and life can return to normal more quickly.

Read more Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Community energy sharing challenges and solutions

Oliver Crowder from Saltwater Solar reports on a remote community solar system he helped set up more than 10 years ago.

Read more Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Breaking the barriers to innovation

Rob McCann looks at the big sustainability innovations of the past, and implores us not to become a nation of laggards.

Read more