Breaking the barriers to innovation

Rob McCann looks at the big sustainability innovations of the past, and implores us not to become a nation of laggards.

On a recent rainy Wednesday morning, I was flicking through an obscure, dusty old book called 150 Years of Photo Journalism in a local second-hand shop. On one of the pages, I was struck by a black and white picture of a bizarre, phallic looking ‘car’ called La Jamais Contente (which of course means ‘the never content’ in French) from 1899.

Not only was this the first ever to break the 100km/hr barrier, it was also fully electric. As it turns out, we’ve had electric cars long before the combustion engine, even as far back as the 1830s, when Robert Anderson, a Scottish Engineer, built a one-way-trip-only, electric modification to his carriage.

Fast forward to the early 1900s and about a third of all vehicles in the US were fully electric, with multiple charging stations built in major cities like Philadelphia, New York and Baltimore. For various reasons (including major discoveries of oil), this innovation was mothballed1, and over a century later was sadly doomed to suffer silly political barriers and discrediting by private interests.

This old innovation, however, is roaring back into fashion, thanks to bold ingenuity and relentless industriousness by the likes of Tesla and BVD. So how does this happen with innovation? What gets in the way in Australia and around the world? And how can we improve things? Let’s take a closer look.

Is innovation really ‘sustainable’?

There is a strange dance between innovation and sustainability. Innovation harnessed the laws of thermodynamics to run the combustion engine, but at the same time has changed the chemistry of the atmosphere and oceans. Combustion of coal, oil and gas has propelled humanity to unimaginable living standards, but in doing so adds about five atomic bombs worth of heat energy to the climate system per second2. Later came nuclear energy, which was a victory for physicists, but its development started the Doomsday Clock. EVs are great, but mass lithium mining for EV batteries isn’t pretty, and so on.

The reality is, we can never go back, nor can we stay on this same path, so the only way out is to innovate more. We need to ensure that the innovations we pursue are positive for all, the dangerous ones are harnessed, and the bad ones are kept at bay, if this is even possible. Such is our conundrum, and perhaps the biggest challenge humanity faces this decade.

How and why does innovation come about?

At 10:34am on December 17th, 1903, you may have been forgiven for thinking that powered air flight was not possible, nor would the sight of an aeroplane have even entered your mind. A minute later, sure enough, it happened, through painstaking trial and error by the Wright Brothers. Now planes are everywhere.

If you had gone into a coma at some point in the early 2000s and woke up at Flinders Street station in Melbourne today, you would be wondering how or why, all of a sudden, everybody is staring at these small handheld rectangular objects with screens, completely unaware of their surroundings and bumping into one another like NPCs in a video game.

We’ve had the wheel probably for over 5500 years, but it didn’t dawn on us until one day in 1970 that putting these wheels under your luggage is better than lugging it around airports without them. Now wheels on suitcases are ubiquitous and you wouldn’t buy one without them.

There were people on horseback watching cannonballs being fired in the American Civil War, who also lived to later see nuclear weapons detonated. You get the picture.

Innovation and its ‘creative destruction’ is not smooth, nor is it predictable or linear. While the process itself is sometimes arduous and long, discovery and innovation occur in leaps, and come from observing, creativity and thinking, tinkering, research and development, persistence, and sometimes complete and utter chance.

For sustainability, this is a particularly interesting theme. Necessity is the mother of invention, as the saying goes, and we are in a time of urgent necessity. This necessity being we need to continue to improve or at least maintain living standards for eight billion humans and their future offspring without stripping the world bare of its natural capital, polluting with impunity, and worsening or stealing from the future.

This is why innovations which improve energy efficiency, reduce emissions, maintain or protect natural resources, water, food, ecosystems and human health are all the rage right now. For technologists, inventors and innovators in this space and time, the potential rewards are great, and the benefits for those who choose to adopt such changes can be enormous.

The word innovation means to ‘renew, or to create a novel change, experimental variation, new thing introduced in an established arrangement’. This is our task in sustainability.

Where’s my hoverboard?

For those paying attention, it’s 2024AD and we are not living in the green, Jetsons-like technological utopia we once expected. Yes, computing power and efficiency, as expressed through Moore’s Law, continues to race ahead at mind-boggling speed and scale, having many flow-on effects for sustainability, both positive and negative. So too is some medical innovation, energy storage, efficiency and production, and others. This is good news.

But at some point, and contrary to popular belief, many important industrial-scale areas of innovation and adoption which we have enjoyed in previous times have hit a brick wall. There are a few theories as to why this is; like the fact that the ‘low hanging fruit’ has already been exploited, we have had the big and easy wins, and that people, both individually and socially, are comfortable with the status quo. The aircon works fine, the power stations are already built to run on coal, plastic is cheap and abundant, and copper for broadband internet is ugh… well I don’t know about that one.

Once something has been around for a long time, we get used to it, creating a huge ideological barrier to innovation or even wanting to take the risk. Indeed, the longer a certain way of doing things has been around, the more likely it is to persist that way into the future. This is called the ‘Lindy Effect’. We also remain stuck on certain areas of physics (e.g. Newtonian, Einsteinian), which constrains us to current speeds and travel methods.

Believe it or not, while our knowledge is increasing, the rate of disruptive innovation is declining at the same time, in almost all sectors3. As Eric Weinstein correctly stated, if you were to remove all the screens from your home, how do you know you aren’t in 1970? Then there are corporate monopolies, private interests and lobby groups who openly like to scuttle innovation which are counter to their interests. The list goes on.

This is a problem, because we need ‘new orchards’ of innovation to explore and scale, not just for sustainability, but because unfortunately it is critical to economic prosperity and to usher in the fourth industrial revolution; one of lower emissions, better technology and higher living standards.

Australia—where the bloody hell are you?

As I explained, electric cars, once targeted to the savviest consumers in the early 1900s of the US, were scuttled for almost a century. They made a reappearance back in the ’90s, but were dorky-looking and gimmicky, and you couldn’t really buy or use them as a normal consumer and road user. Now they are here, they are cool, and their capability is extraordinary, but for several years we in Australia kept them at bay, and scared the market away through a misinformation campaign and statements like the following in The Guardian:

“It’s not going to tow your boat. It’s not going to get you out to your favourite camping spot with your family… are you going to run the extension cord down from your fourth-floor window?”—Scott Morrison in 2019, whilst Prime Minister.

Imagine being president of Ford Motors, or Tesla, or BVD, looking at potential markets for your new EV range and hearing this pronouncement to the world that, not only did we not want electric vehicles here, our leaders were either a) in the business of disinformation, or b) have not spent the time researching or thinking logically about an innovation which can have almost immediate and direct social, environmental and economic benefits for your nation (and can tow a boat, and go to your favourite camping spot). The failure rests on both sides of politics over the past few decades.

This is unfortunate because we are an inventive bunch in Australia. The CSIRO invented Wi-Fi in the 1990s. The University of New South Wales has been, and continues to be, a world-leading pioneer in the research and development of solar panel technology. Aussie researcher Edward Holmes from University of Sydney was the first to sequence COVID-19 and publish his results with the world so we could figure out what on earth it was. We spawned the Hills hoist and the electric drill and gifted these to humanity. We have some of the brightest minds on the planet, yet our innovation and industriousness in many areas has been on a steady decline.

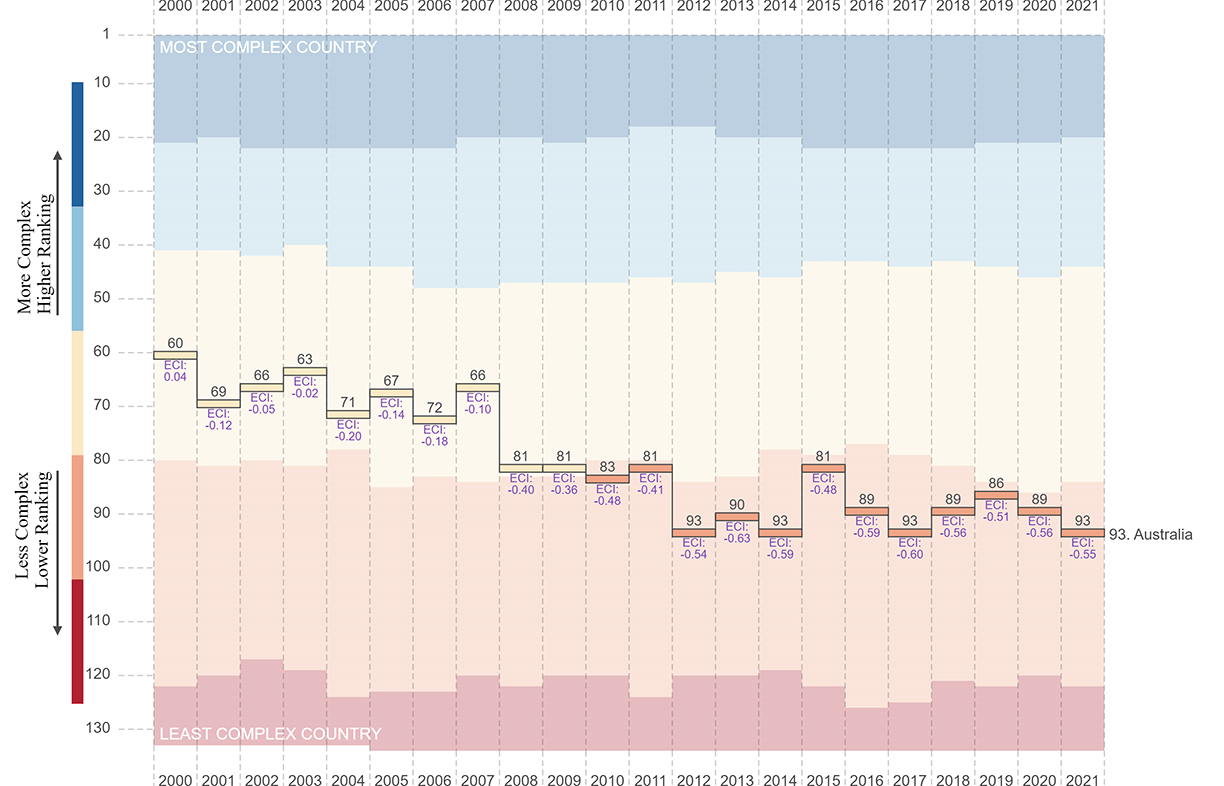

Let’s take one indicator—economic complexity, which we can define loosely as productive capabilities which includes inputs, technologies and ideas that, in combination, determine the frontiers of what an economy can produce. It’s the amount of things we do and make, and can include all sorts of things like manufacturing, machines, inventions, books, movies and collective knowledge4.

Even since the year 2000, when much of our industry had already been offshored, our economic complexity continued its downward slide. See the below image from Harvard’s Economic Complexity Rankings showing this decline.

We in Australia rank 93rd on the economic complexity index, falling just behind Uganda, and being beaten by a whole raft of countries like Kazakhstan, Honduras, and El Salvador, which despite all odds (social, political, economic), have a more complex economy. This is an unconscionable risk for the sustainability of our society and economy.

This does not mean that there aren’t innovative Australian suppliers, researchers and manufacturers. There are many; I have the utmost respect for them and speak with them regularly, and they are working tirelessly to beat the status quo and get their products out to market and provide a positive impact. The issue is that they face absurd social, political, financial and logistical barriers which they shouldn’t have to face in an advanced country like Australia, especially when there is so much to gain by innovating, and so much to lose by not.

Barriers to innovation

Let’s zoom in a bit closer, and look at the barriers to adoption (once the innovation is ready to go). When you work in sustainability, trying to make positive changes in the perhaps small corner of market over which you may exert some sort of influence, you soon arrive at the realisation that, in large part, markets and organisations are not always efficient. They are expedient, and they are terrified of reputational and financial risk. Sometimes this risk is justified, often it is not. The risk of innovating is seldom weighed up against the risk of not innovating.

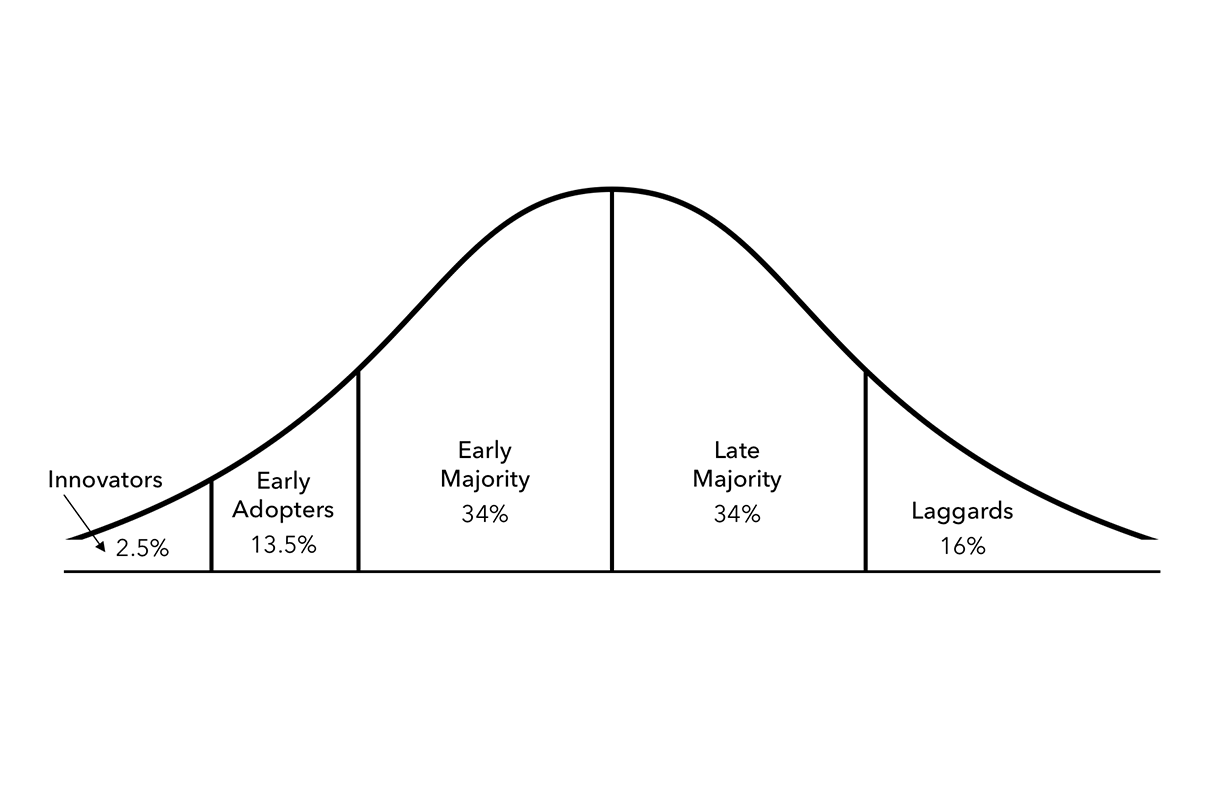

Infrastructure, where the lion’s share of global emissions originate5 and which is under tremendous time and budgetary pressures, is particularly hard to influence, and as such, risk tolerance is understandably quite low. The famous diffusion of innovation curve (shown below) is a basic concept, and shows the trajectory of the adoption of innovation. The uphill battle is difficult, but at a certain point, adoption picks up steam, and the ‘laggards’ do what laggards do—they lag.

Some years back, I proposed a very low-risk, circular economy initiative on a small section of a project and, in a Zoom meeting, pitched it to the big wigs on the project who made the final decisions and had custody of the credit card, so to speak.

The engineering had been done, standards were met, the supplier was ready to go, the costings were done, and it had been trialled in other states with no issues. I just needed the final OK. In front of over 20-plus attendees, the person at ‘the top’ shouted down the microphone on his laptop, with elevated blood pressure snarling: ‘NO WAY! Do you think I am going to take on that sort of risk for the project and the investors!!?’. This is why infrastructure sustainability is the most fun.

I asked some peers with boots on the ground in the industry, who are also trying to push the adoption of sustainable innovation daily. Charles Pachulicz, a sustainability manager and materials specialist at INECO who works on major transport and renewable energy projects, says:

“Hesitation on projects can be driven by perceived cost or program impacts. If a new product is not a like-for-like replacement, this can generate concerns about rates of construction which have been assumed during the tender process and as such may lead to a reduced efficiency during construction.

New and innovative products can often have price premiums due to a lack of economics of scale. If a project has not set aside money to be spent on such products then there will be a reluctance to take on additional cost for no tangible benefit. As such, the influence of sustainability performance in securing contract award can often be overshadowed by who has the cheapest price or can complete the works in the shortest amount of time possible.”

That aside, Charles is excited about the future of low-carbon steel, and manufacturing using innovative methods in places like Whyalla, South Australia.

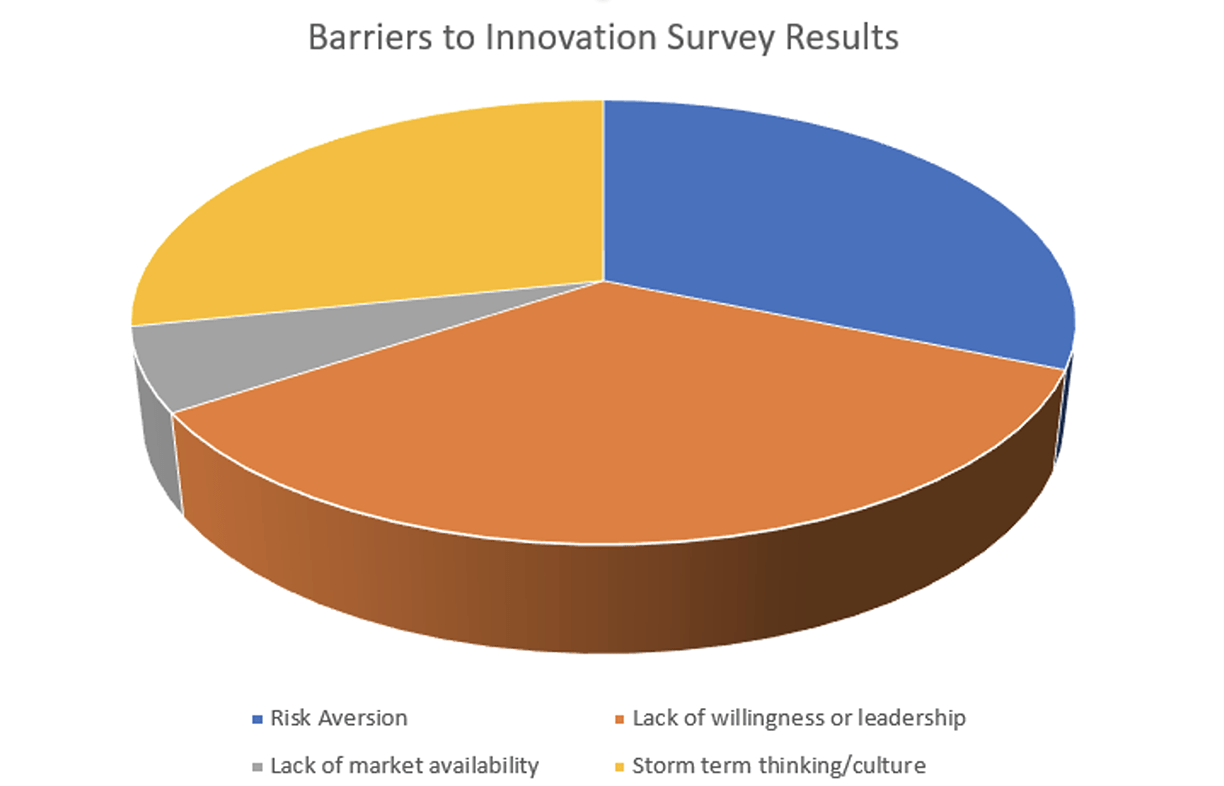

Joseph Schmookler’s “demand-pull” hypothesis implies that innovation comes about from market demand. A closer look suggests otherwise. In fact, I sent out a survey on LinkedIn asking what the biggest barriers to innovation were, be it on a project, within an organisation, locally or nationally. The responses were from suppliers and manufacturers to organisational and executive level in sustainability, innovation and infrastructure sectors.

The results are interesting because, tallying up the above, only 6% stated that market availability (as in, having these innovations ready to go and suppliers available) was a barrier. That means 94% was attributed to a lack of things like willingness and leadership, short-term thinking and culture, and risk aversion.

What this seems to say is that, at the adoption level, many of the innovators in sustainability can see the writing on the wall; they know that there is a problem with how we do things, and they are steaming ahead. The walls they are running into in adoption and acceptance of their innovations are not necessarily technological, they are coming from unaccommodating organisations with a high time preference (short-term thinking), parsimonious commercial teams, outdated standards and risk-averse managers.

The adoption of innovation takes leadership, calculated risk tolerance, vision and a cautious disregard of the status quo. Henry Ford, industrialist and Founder of Ford Motor Company once said, “If I had asked the public what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse.” He had a vision, he disregarded the status quo, he persisted and succeeded wildly.

The ‘laggards’ which sadly occupy the seats in many organisations, and resist or dismiss innovation as woo-woo or risky, are themselves an existential risk to that organisation, and will inevitably be outcompeted by other organisations who are pro-innovation. This has been true since the first use of the bow and arrow. This is also true on a global scale for a country like Australia, if we are not careful.

Full steam ahead

Despite all this, it’s hard to not be excited by the choir of sustainable innovations which are singing on our doorstep, if we were to just open the door to them.

According to the World Economic Forum6, “An innovation tsunami has the potential to wash over the world’s energy systems. With it, disruption and transformation throughout the world economy could be as profound as the shocks of electricity and oil a century ago. The size and scope of today’s energy systems create powerful inertia, but tsunamic forces could swiftly upend businesses and also profoundly alter the outlook for how energy systems affect emissions and sustainable development.”

Some examples. There are companies in Australia and around the world which are in the very early stages of harnessing the power of gravity7, elevating weights when energy is cheap, and capturing the kinetic energy as the weights move downward. You can also capture huge amounts of ‘piezoelectricity’ from heavy objects like bridges and roads, although it’s important to note that these ideas, while simple and brilliant, are in early stages.

Then there is AirSeed, an Aussie company which uses drones and AI, and can plant up to 40,000 seed pods per day (with high success rates) and scale up afforestation and offsets to never before seen levels. According to the website, it’s about 25 times faster and 80% more cost effective than manual planting methods. “Planting trees at scale is vital to tackling the climate crisis and reaching net-zero emission targets,” says Jonathan Dawe, Commercial Director at AirSeed.

How about electric vehicles which don’t ‘ruin the weekend’, and have mind blowing range, power and speed, like Atlis Motors (now rebranded as Nxu, Inc.), or printable solar (again, invented by an Aussie, Prof. Paul Dastoor), which, while lower in efficiency, can theoretically cover an entire building and generate free energy. The innovators are out there and ready to roll out and scale up.

There are countless examples of disruptive and effective innovations which, despite the barriers I’ve described, are there for the taking—for those who are willing. We need to make sure, especially here in Australia, that we don’t become a nation of laggards. For managers and organisational leads, have a crack, take a calculated risk or be left behind. For innovators, do what you do best, break through barriers and never be content.

References

- Timeline of the electric car. bitly.ws/32tvj

- Five atomic bombs per second. bitly.ws/32tvp

- Disruption is declining.

- What is economic complexity. bitly.ws/32tvJ

- 79% of emissions from infrastructure.

- World Economic Forum Report Transformation of the Global Energy System, WEF 2018. bitly.ws/32tvT

- Gravity Energy Australia. bitly.ws/32tw3

Further reading

Climate change

Climate change

Charting possibilities of the blue economy

Mia-Francesca Jones explores the opportunities of the blue economy for oceanic health, as well as human and planetary wellbeing.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy forecasts, hydrogen hype and questions of progress

Alan Pears gives us his round-up of the main energy issues this quarter.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy costs, climate impacts and quality of life

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more