The farmer next door

On a standard surburban block in Melbourne, Simeon Hanscamp is growing enough food to provide his local community with vegie boxes—and himself with an income. Anna Cumming visited him to find out what it takes to be a successful backyard farmer.

This article was first published in Issue 144 (July-Sept 2018) of Renew magazine.

Backyard fruit and vegie gardening is enduringly popular in Australia; one 2014 study found that 52% of Australian households reported growing at least some of their own food at home. Most of us—especially those who live in urban areas—stick to a few herbs and some tomatoes, or at most a handful of fruit trees and a productive vegie patch. But with a bit of determination and a suitable site, the potential is there to scale food production up to ‘backyard farming’.

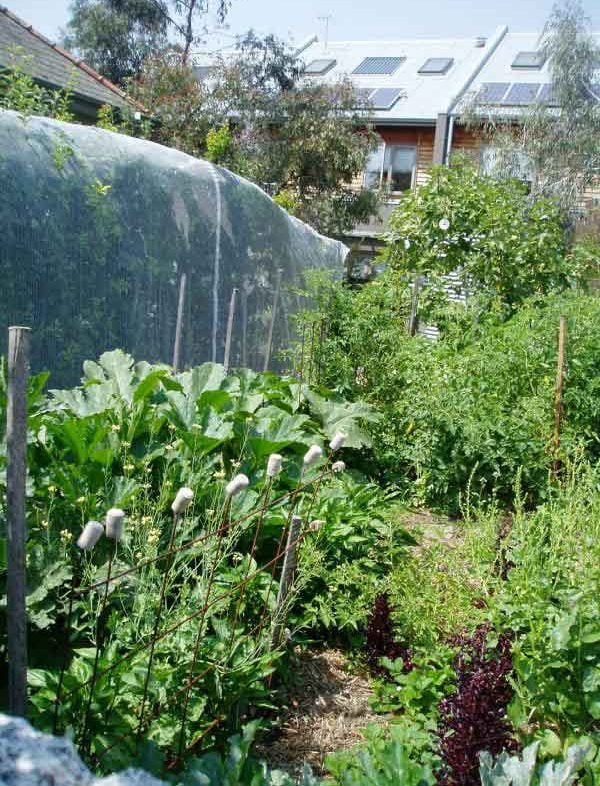

One young entrepreneur in Melbourne has done just that. Both front and back yards of the rental house Simeon Hanscamp shares with two housemates in West Heidelberg, 10 kilometres north-east of the city centre, are laid out in neat, regular-sized garden beds, in which he grows greens and other vegetables. “I have about 220 square metres of growing space, and it produces $200 to $400 worth of food per week, depending on the season,” says Simeon. He sells it to neighbours via a ‘farm gate’ box at the front of the property, and through a vegie box scheme: his subscribers—15 to 20 local families—either collect their weekly boxes from the house, or pay a little extra for bike delivery. Recently, he’s also started attending the weekly farmers’ market at Melbourne University.

Getting started as a backyard farmer

Simeon’s backyard farm is the result of careful research and planning. He got the gardening ‘bug’ when he was involved in starting up a compost heap during his gap year; a few years later he spent time working at Transition Farm, a market garden on the Mornington Peninsula. “It was the best food I ever ate,” he remembers, “and I developed more of an interest in soil biology and so on.”

He also discovered ‘community supported agriculture’ (CSA). “Transition Farm’s CSA program means that around 100 families commit up front to buying weekly food boxes. The farm has a bit more financial security that way and planning production is easier. Typically recipients are also more involved in the story of where their food comes from.”

Inspired to become a farmer, Simeon spent three and a half years researching and learning, and developing his own business idea. “I wanted to be near family and also my partner’s city workplace, so the big question for me was how do I juggle proximity to the city with farming? The answer was urban farming.”

Farming on rented land

Simeon has based his enterprise on the methods of Canadian farmer Curtis Stone, author of The Urban Farmer: Growing food for profit on leased and borrowed land [see box]. “A lot of would-be growers think they need to have their own land, but it’s not true,” he says. “You don’t need to buy land to be a farmer.”

He spent time looking for a suitable rental property, scouring online mapping sites for larger blocks that would afford at least 150 m2 of growing space. “I needed a flat site with good sun access, and importantly, no soil contamination,” he says, “plus an undercover area for tools and for washing and packing produce.”

Of course, the final crucial element was a supportive landlord, as he needed permission to dig up the lawns for garden beds. Along with the West Heidelberg block, for which he and his housemates have a standard tenancy agreement, Simeon is setting up two more farming sites, one in the backyard of a family member’s rented house (with a similarly encouraging landlord) and one on a vacant block in a neighbouring suburb. For both of these sites—totaling an extra 580 m2 of growing space—Simeon pays ‘rent’ in the form of fresh produce. He says owners of land are often enthusiastic about seeing it used for productive purposes. “I also plan to explore with the local council what scope there is for reducing the rates on sites like mine that are used for primary production, as an extra incentive for landlords to get behind urban agriculture.”

He admits that there is an issue of security of tenure when land is leased. This has led him to stick to infrastructure that’s temporary (such as his plastic sheet greenhouse) or moveable (such as his produce wash tables and drying racks), so that he could “move in a week and set up in a new site” if necessary. On the plus side, he’s not servicing a large mortgage for land purchase.

Refining the system

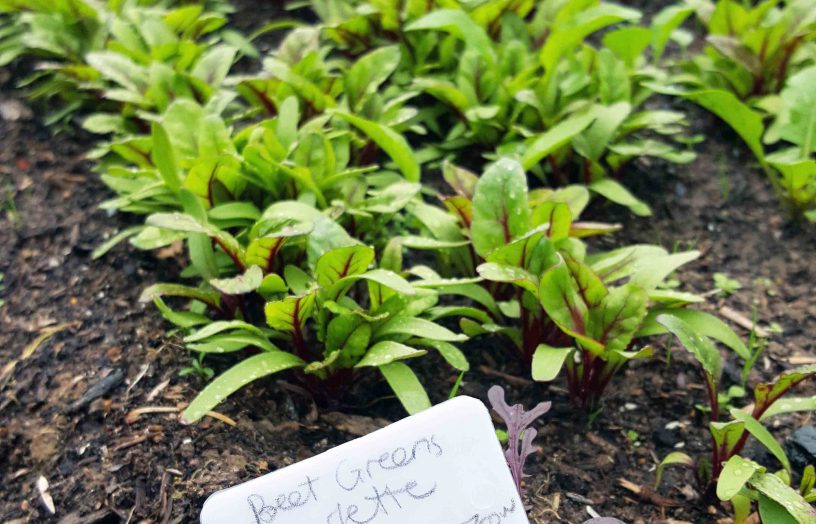

Simeon got his farm started in earnest a year ago, and has been refining his crop selection and systems. He grows herbs, turnips, carrot, beetroot, spring onion, cucumber, tomatoes, zucchini and a wide variety of greens, concentrating on crops that are high value, quick to grow and with a good yield. Standardised garden beds—75 cm wide and 7.5 m long (and Simeon uses half-length beds where space is limited, and double-length where space permits)—help with record keeping, which is vital for learning and ensuring a profit. He says the size also makes the day’s workflow easier: “You do a task in one bed and then move on to a different task in another. It’s important to think about what works ergonomically for your body if you want to be doing this for thirty years!”

Simeon’s system follows organic principles and weed strategies, with biological organic compost inputs and no chemical sprays. “Compost is really important, and not practical to make on a large enough scale myself, so I get it from a local nursery supplier,” he says. “I add around 60 litres per bed at crop changeover.” He also uses pelletised organic fertiliser, and a combination of rainmakers, micro sprinklers and moveable drip lines for watering.

He says pests haven’t been a big problem, and that providing plants with the nutrition, airflow and water they need ensures they’re robust to help resist pests. “I also plant for abundance, planning to produce 25% more than I need so that the odd bitten leaf doesn’t matter. And I trade vegies for pest management advice with a local entomologist.”

One area that’s a particular concern for Simeon is weeding. “Farmers can spend a lot of time weeding, and my time is my most valuable commodity, so weed control and mitigation is really important.” He uses a combination of methods including regular hoeing while weeds are small; planting transplanted crops into weed mat with holes cut in it; and ‘stale seed bedding’ for direct seeded crops. This involves waiting for the weeds to germinate, then smothering them with black fabric or using his gas-powered ‘flame weeder’ to wilt the weeds and provide a clean bed for the crop.

Sized for market gardens, the flame weeder is just one of the specialised tools Simeon is collecting as funds allow—all of them just the right width for his garden beds. His favourite is his ‘tilther’, a small-scale cultivator powered by the motor in a battery drill: it tills just the top inch or so of soil, mixing compost and fertiliser into the direct seeding zone without disturbing the deeper soil. Other tools include a precision seeder and a broad fork for soil aeration, and next on his list is a drill-powered greens harvester to speed up that job.

What’s the payoff?

Having got off the ground with a $15,000 startup loan and nine months of a Newstart-equivalent wage via the government’s New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS), Simeon considers his business “still in startup mode, but I’m not going backwards”. He plans to build it up to the point where it provides him with a living wage, and possibly create a local job or two.

Beyond the financial rewards though, he takes satisfaction in growing food in a way that’s transitioning to a different economy, one that’s local and includes trade and barter. He currently swaps produce for bread, goat milk and bike repairs. “There are way more benefits to being part of a local economy than I can tangibly count,” he says. “How do you quantify being known and having a place in your community?

“This is my full-time job. To derive an income from food should be possible, and to do it in the suburbs means that the consumer gets to meet the farmer, which lets people engage with where their food comes from. I love seeing parents bringing their kids to buy food from my farm gate—it’s an important part of village learning.”

Based on Curtis Stone’s model

- Farm on multiple sites if necessary, up to around ¼ acre (1000 m2), an ideal size for one person

- Standardise garden beds to 75 cm wide (suitable for conventional market gardening tools, e.g. cultivators) and around 7.5 metres long. This growing area will produce a sensible volume of in-demand produce, not too much to manage

- Choose high value crops: high yield per square metre and a high sale price (e.g. not pumpkin and cabbage)

- Choose crops with a quick turnaround to maturity, ideally less than 75 days

- Limit the types of crops to around ten popular items: those with high demand and low market saturation.

Simeon has been following the development of Paul Hawken’s ‘Drawdown’ project to reduce global warming with great interest. The project brings together peer-reviewed science on the top 100 solutions to climate change that are available now, each reducing the amount of carbon emitted, with the ultimate goal of ‘drawing down’ the total amount of atmospheric carbon.

“I went through the Drawdown list and found that I could tick off about 15 solutions that my business is already engaged with,” says Simeon, “including regenerative agriculture of course. There are at least five more that I have targeted for the near future, such as solar, an electric bike and biochar for carbon sequestration.”

For more on the Drawdown project, see our article in Renew 143.

At Westwyck, an eco community in Brunswick in Melbourne’s inner north, a small communal food garden is shared by 12 households. Started in 2007, it has 18 m2 of vegetable beds, a small area of espaliered fruit trees, and a fig tree.

For several years the garden’s yield was recorded, and from 2011 to 2014 amounted to over 600 kg of produce, including 154 kg of fruit, 440 kg of vegetables and 17 kg of herbs—and this is probably an underestimation as it relies on each household keeping accurate records of produce harvested.

“The yield is tempered by the need to cater for a community, rather than just a single household,” says Fiona Barker, who helps manage the garden. “Our focus has been on crops that produce for long periods of time (‘cut and come again’ crops) and those that don’t take up too much space.”

Elsewhere in suburban Melbourne, Kat Lavers is taking a different approach to intensive backyard food production.

Like Simeon’s, Kat Lavers’ backyard is almost entirely devoted to food production. However, the Northcote resident has quite different aims for her urban growing enterprise. “I’m not trying to make money; I’m just trying to feed myself and my partner,” she explains. To this end, she has been experimenting and developing her garden using permaculture principles, aiming for as much diversity as possible. The result is a great example of an intensive, productive small-space urban ‘kitchen garden’.

Kat bought the property 10 years ago, and named it ‘The Plummery’ after the wild cherry plum that was the only tree she retained. “All the rest were ornamental species, so I replaced them with fruit trees.” The block is only 280 m2, with 100 m2 of garden—far smaller than Simeon’s place—but that didn’t daunt Kat. “Serious food production” kicked off about six years ago, and she says it’s surprising and humbling what a relatively small space will grow for them.

“I aim for a diversity of crops all year round,” she explains. “We do a bit of preserving to fill gaps and have more variety for more of the year. And we focus on the things that make sense in a small area: things where you can eat most of the crop for most of the time it’s in the ground. For example, eggplant has a long growing season with a short fruiting season so I only grow a small amount of that.” She also concentrates on crops that are easy to grow but expensive to buy, such as berries, and avoids those that are space-hungry and cheap, like potatoes.

The list of produce has evolved “through a combination of learning to grow what we want to eat, and learning to eat what we want to grow,” Kat laughs, and includes grapes, mandarins, pomegranates, plums, nectarines, feijoas, avocados, berries, hazelnuts, almonds, garlic, spring onions, silverbeet, tomato, zucchini, beans, peas, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, carrots, beetroot and basil.

She grows different varieties of many crops, after doing trials to see what works best in her garden; this approach helps with stability and pest resistance, and provides further eating variety and different harvest times. “I also plan my planting to avoid an overabundance of any one thing. I’m not aiming for a massive bumper crop of zucchini, but a manageable-sized crop, for example. I’m gradually learning to match what our kitchen needs.”

Because of soil contamination, Kat uses raised beds. She makes her own compost with the help of her flock of 10 quails: the 6 m2 floor of their aviary doubles as a ‘deep litter’ composting system. The birds add their manure to a layer of carbon material like wood shavings, and aerate it by scratching for bugs. Kat adds food scraps and weeds, and harvests around half a cubic metre of compost every 6 to 12 months.

As for pests, the main ones are possums and rodents. “We have a domestic-scale electric wire that runs around the fenceline. It’s highly effective for keeping out brushtail possums—we’ve had no failures since we installed it two and a half years ago. It also keeps our cat confined to the back garden, where he deters and hunts rodents; native animals in surrounding parks are also protected!”

For the last couple of years, Kat has kept data on everything the garden has produced. In 2016, the tally was over 350 kg of fresh fruit and vegies, plus quail eggs, honey and mushrooms. “It’s enough to supply our household of two people plus guests, year round, except for pumpkins and potatoes,” she says. She estimates that she spends at most $300 a year on her garden now that it’s established—mostly on quail food, and a small amount on seeds and seedlings. While she hasn’t done the sums to work out the value of the food she produces, she’s very confident that she’s saving money.

So can anyone with a backyard do the same? “I just wouldn’t have the time” is a comment Kat hears a lot. On average, she spends four hours a week maintaining her garden, plus harvesting time. “Growing most of your own fresh food like this takes so much less time than people realise,” she says. “Time to spend in the garden probably isn’t the barrier many people imagine it to be, though it does take time to learn the skills needed to care for the soil, have healthy plants and get good yields, as we’ve largely lost the incidental learning from parents and grandparents.

“I find it a lot more convenient having the fresh vegies where I need them,” she continues, “and it saves shopping time.”

Kat is not going to stop gardening any time soon. “I started growing food because I was a poor student and wanted to cut my fresh food costs down. Once I began, it quickly became about freshness, flavour and a better understanding of climate change—our food systems that don’t really serve people well, and food resilience. And I get so many other benefits from the garden: relaxation, entertainment, good physical and mental health. I’d love to spend more time out here.”

This article was first published in Issue 144 (July-Sept 2018) of Renew magazine. Issue 144 has smart home technology and smart electric heating as its focus.

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Community

Community

Game of life

The Adaptation Game is a new interactive board game that uses science and storytelling to simulate how you and your community can respond to the next 10 years of climate change.

Read more Reuse & recycling

Reuse & recycling

Community eco hub

Nathan Scolaro spends 15 minutes with Stuart Wilson and Michael McGarvie from the Ecological Justice Hub in Brunswick, Melbourne.

Read more