Game of life

The Adaptation Game is a new interactive board game that uses science and storytelling to simulate how you and your community can respond to the next 10 years of climate change. Co-founder Ben Pederick speaks to us about how the game works and why local councils are getting on board.

NATHAN SCOLARO: What seeded the idea for The Adaptation Game (TAG)?

BEN PEDERICK: TAG is the merging of my PhD on climate tools for local councils, and a group of artists and change-makers designing games for change. I’m researching and prototyping a toolkit for local governments to scale climate science down into immersive experiences for people in their communities. Specifically, I proposed the idea for a game or a drill that would take climate science, put it in the world around you and be played by people in their own lives and communities—in connection with councils.

This research led me to the troupe of remarkable minds and people at Amble Studios, who had been actively designing games systems with the same intention for years. The combination very quickly found its feet in a shared vision, which has now taken over a good portion of our lives—we’re in 12 councils at the moment. The goal is to make it easily available to anyone.

The game is about responding to climate crises from a local level—why was that important?

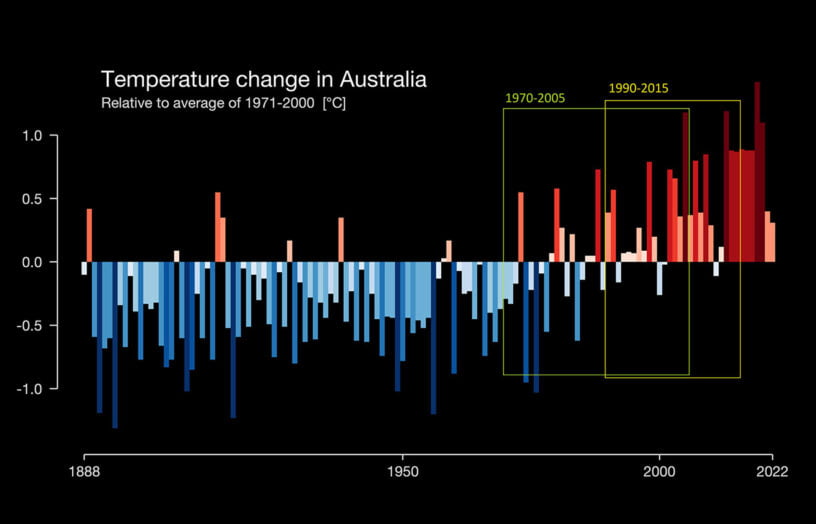

Climate change is now baked into the system, and in general, communities are dangerously underprepared for the risks they will face. Importantly, there is a remarkable amount known about climate change at all scales. That knowledge-action gap, the gap between what we know and how effectively we’re able to implement it, is what TAG is seeking to fill. It’s seeking to find a way to make all of that knowledge available and useful for people in their world.

We recognised local governments have a critical front-line role in climate change. They’re directly responsible to their constituents in a way that no other level of government is. So we sought to make a tool to implement and operationalise climate science that sits between councils and their communities.

What was the first council you worked with?

We went to Merri-bek council and connected with Donna Luckman. Donna is an exceptional and long-term leader working in environmental change and climate. She understood TAG quickly, the idea that we would be going to make a serious game to be played by the community. Hence, the game was co-designed with Merri-bek, and its first draft was set there. Through that partnership we got the community networks, all that local expertise and council knowledge, which is just extraordinary.

Our team, led by the amazing Bec Dahl, devised a method for downscaling climate science into local future pathways in Merri-bek. This way the game can depict what kind of climate events and what scale we will expect to see happening for the council over time. From there, much testing and refinement came to create a working tabletop game.

Tell us about the game—what’s involved and how you play.

It’s a four-person game with a facilitator, and players roleplay themselves, and the game is a time-travelling game. You travel two years at a time, with three or four rounds into the future. It’s all set where you live, around a map of your council area in the middle.

As the game progresses, things happen in the world, with news items that are all climate-related. So you see stuff about the Great Barrier Reef or what’s happening in Africa, it’s all quite dire, but the focus of the game comes back to what you can do to adapt. So even though you’re facing the ongoing and accumulating threats of climate change, the issues that you are addressing are local ones, things that are going to happen in your council and affect you directly.

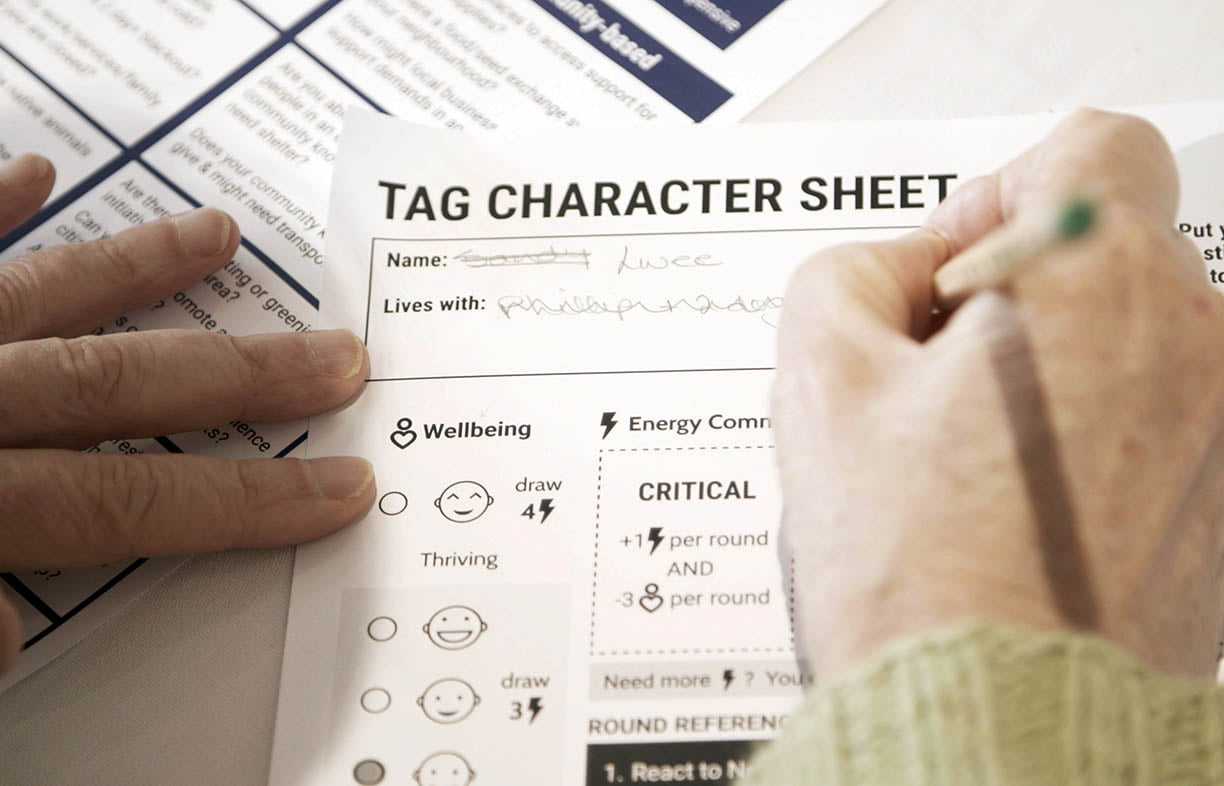

You don’t get to play as president for a day; instead, the game gives the superpower of adaptation. All the things you know or can imagine doing to adapt to the challenges you face, including solar panels, starting a community group, changing a garden, those things. And each round you get resources and you spend those resources to perform your adaptations. You also have a character card that tracks your journey. Another layer is you get to vote as a group on real council programs, and you get to choose which ones you want to play.

Each round, you confront a new climate-related crisis, as projected through research for your council area—maybe a heat wave, flood or a fire. And so you get to see where you are in relation to the impacts of that event; is your house in the flood, or near a burning forest? These events impact your individual and community wellbeing, but your adaptations can help protect you, if they respond to the risk you face.

So it’s not a win or lose situation?

No, it’s a story game. It is an experience and empathy tool to the extent that you get to experience what adaptations can do for you, and you get to experience what collective thinking and doing can really bring you. We find that people collectivise their sense of wellbeing, and feel good about what they realise they can do together. We’ve had people play really right-wing individual libertarians who have been drawn back into a sense of collective wellbeing at the end as they see other people suffering. The end of the game is not, oh, it’s all over. It’s clearly going to go on into the future, but people are able to reflect on what they learned and how they feel. Players consistently report that at the end of the game they are left feeling both concerned but inspired, scared but hopeful.

So the big takeaways are around realising the power of the collective to adapt to climate crises?

Yeah. I think another massive takeaway is learning what is actually happening on your street—what would happen in two or four years’ time in your town and coming up with a bunch of ideas that could help you in real life. All of that information is available online and through your council, so in the game we provide links for people to go and check all the science. The game is very much an engine that takes quantitative knowledge, like hard data, and turns it into a story.

What are some of the experiences people have had playing the game?

It is rare that people don’t come away quite affected. In some cases people are given a way of seeing the things they can do in a new and positive light. One woman discovered that all the community work she does without expecting any reward was the difference in a future disaster. Another man had his assumptions about self-reliance upturned by the success of two older women whose focus on community wellbeing ended up making their own resilience strong. Overall, we think of the shift as being from overwhelming fear to specific risks that you survived and realise you have the power to affect. It is an electric and empowering game.

How can people play it?

We are working with local councils, so if you want to find out more visit us at tagclimatedrill.org, or get in touch at tagclimatedrill@gmail.com to learn about how we can bring the game to your local council or community group.

Further reading

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Tradies and the transition

Do we need as many tradies for electrification as many think? Not if we are innovative, writes Alan Pears.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Double glazing on the (very) cheap

Do we need as many tradies for electrification as many think? Not if we are innovative, writes Alan Pears.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more