Powering Indigenous communities with renewables

Many remote communities rely on polluting and expensive diesel generation. Jodie Lea Martire seeks out the Indigenous entrepreneurs and partnerships driving a more equitable renewable approach.

The United Nations has developed goals for sustainable development, including goal seven: “Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.” Australia’s strong renewables growth has meant that by late 2018, 21% of our energy came from renewable sources, with one in five homes powered by rooftop solar. Let’s take a look at whether Indigenous Australians are getting a fair share of this renewable boom, both as consumers and as entrepreneurs.

There is no easy way to quantify Indigenous access to renewable power, partly because it lacks federal oversight. State governments, utilities, developers, infrastructure companies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and Aboriginal groups have each connected Indigenous communities to off-grid solutions, but many remote homelands and outstations—communities of fewer than 100 people—rely on diesel generation.

Diesel can cost $2/litre in the outback, and the pump price doesn’t include transportation to community, via road or even air in the wet season (imagine your freezer getting disconnected when your road into town gets cut by flooding … for three months a year). The short-lived First Nations Renewable Energy Alliance, announced in early 2017, reported that some diesel costs reached $5000 per quarter, while residents of remote NSW communities, at the end of standard ‘poles and wires’ networks, said locals had power bills up to $3000 per quarter.

Of the 180 Indigenous communities in Western Australia, the regional government-owned utility Horizon Power services 53. Seven large communities currently have solar, and six large Kimberley communities will receive it in the next two years. The remaining 117 outstations are managed by WA’s Department of Communities, which in 2015–16 spent $16.29 million on diesel for Indigenous communities. Meanwhile a 2016 Centre for Appropriate Technology (CfAT) survey of 401 of the Northern Territory’s 630 homelands and outstations found that 104 (26%) had a hybrid power supply combining solar and generators, 58 (14%) had solar, 92 (23%) had a generator only, 90 (22%) had access to the grid and another 55 (around 14%) had no power at all.

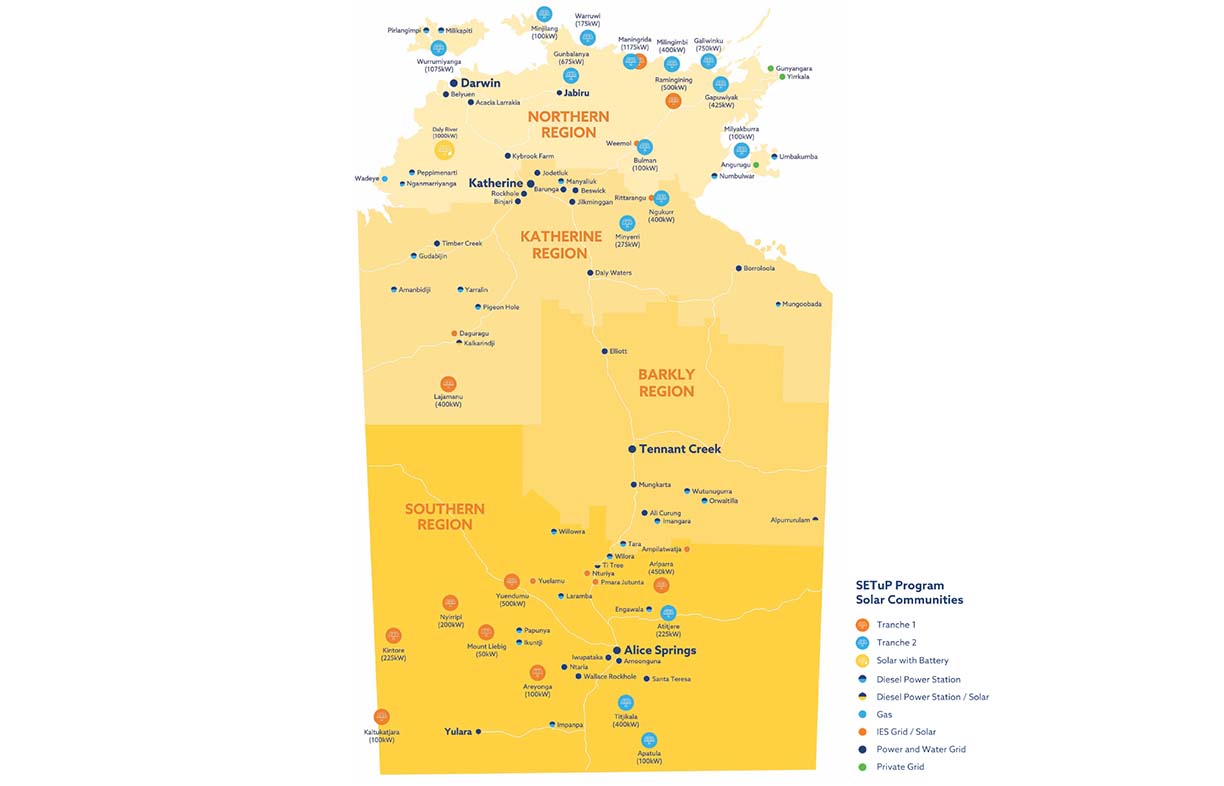

The non-profit subsidiary of NT’s Power and Water Corporation, Indigenous Essential Services, completed the ARENA-funded Solar Energy Transformation Program (SETuP) in late 2019. This sees the integration of 10 MW of solar into existing diesel power stations in 25 remote Indigenous communities, saving around 15% on fuel costs and an estimated 94 million litres of diesel over the program’s 25-year life.

The governments of South Australia and Queensland provide slim solar opportunities, with a small solar system in SA’s Oak Valley community and five in Queensland, including Doomadgee, Mapoon and a hybrid solar system in the Lockhart River area.

From these statistics, you’d never know that solar power is a perfect renewable match for outback Australia. Our landmass receives a world-leading 58 million petajoules of solar radiation a year, the highest per square metre of any continent and ten thousand times greater than our energy needs. Alice Springs, for example, has 300 sunny days per year, 200 without clouds.

Rather than connecting poles and wires to far-flung settlements, off-grid distributed energy systems have lower infrastructure costs, plus engaging Indigenous communities in design, construction, maintenance and operations capitalises on their deep local knowledge and enhances First Nations’ autonomy. The variation between sites and the small scale of interventions also provide a valuable testing ground for innovative developments. Beyond reducing costs for Indigenous residents, solar systems increase energy security and reliability and allow small businesses to take root and thrive. Roma Puertollano, whose Chile Creek community in WA received a small-scale solar system, said “We’ve got power, so we can have tourists. It’s as simple as that!”

One flagship solar program was Bushlight, funded in northern Australia by the federal government’s Remote Australia Strategies (RAS) Program between 2002 and 2013. An Alice Springs not-for-profit, the Indigenous-controlled Centre for Appropriate Technology (CfAT), ran Bushlight until it closed. In total, CfAT’s Bushlight installed more than 150 stand-alone power systems in remote Indigenous communities. Before each construction, a process of community energy planning would map the number of residents and their electricals, both essential (e.g. fridges, lighting) and discretionary (everything else).

A Bushlight system would incorporate a solar array and battery. A key innovation was CfAT’s easy-to-read energy management unit (EMU), a wall-mounted box with a fuel gauge, power meter and timers. Green lights display the power available for the community’s discretionary use, and a yellow light shows the power for the separate circuit for fridges, freezers and lights. By using reliable technology and investing in community collaboration and training, well-installed systems extend asset life (particularly of the battery) and can last 20 to 30 years. CfAT only had to replace one battery set, because the community engagement had helped residents understand how to use their solar system and its stored energy.

Responsibility for maintenance of the Bushlight systems has now passed to a range of stakeholders, but Bushlight still receives calls from remote communities asking for help with their stand-alone power systems.

For outgoing CfAT CEO Steve Rogers, the longevity of the Bushlight systems is one of the organisation’s greatest successes, “and I put that down to the community engagement effort.” Another reason for Bushlight’s success was that it was a long-term, Commonwealth-scale project. Bushlight is just one of CfAT’s many achievements since its founding in the 1980s, with decades of providing fit-for-purpose technology and infrastructure in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, employing Indigenous workers where possible. CfAT’s work includes power, water and digital connectivity, built infrastructure, training and skills development, as well as facilitating research and policy. Another recent achievement was designing and building the infrastructure, including a 10 kW solar system, at Koongarra homeland in Kakadu National Park. Jeffrey Lee, Koongarra’s traditional owner, successfully fought French company Areva—which wanted to mine the site’s uranium—and had his country integrated into the national park in 2013.

Issues which CfAT has faced over the years include learning from their past “commercial naivety” to become a “fully commercial not-for-profit organisation”. Rogers believes that CfAT lost their Bushlight contract, for example, because they didn’t make an effective business case for the community engagement that they know is so crucial. Rogers sees this lack of commercial acumen as an issue for many small-scale Indigenous organisations and NGOs as they grow.

This is not an error CfAT has made with their commercial subsidiary Ekistica, born from CfAT’s expertise in 2007 and now a private company with 28 staff and an annual turnover of $6 million. Ekistica’s first project was Bushlight India, which delivered Bushlight to under-served areas of the subcontinent and won the Engineers Australia Sir William Hudson Award in 2011. Ekistica developed the Urja Bandhu wall unit (an adaptation of the EMU), which could limit energy consumption based on the household’s budget. From these roots, Ekistica is now the project management engineer for Townsville’s Ross River Solar Farm (148 MW), and has also completed a 19.8 MW expansion to South Australia’s Waterloo Wind Farm and the installation of eight solar minigrids in the Cook Islands.

Ekistica makes another valuable contribution to renewable energy through its management of the Desert Knowledge Australia Solar Centre. This demonstration facility, located just outside Alice Springs and operating since 2008, showcases 39 market-ready PV technologies which can be visited by the public. The centre’s website also provides free access to the datasets for each technology and for local weather data. Ekistica also collaborated with the Intyalheme Centre for Future Energy—the organisation driving the innovations behind the NT’s goal of 50% renewables by 2030—to publish the Off Grid Guide in 2019, outlining best practices in planning, deploying and running remote solar systems.

Alinga Energy is another Indigenous consultancy on the rise. Djaru–Australian founder Ruby Heard first worked in renewables in San Francisco, but after 2½ years which included “saving Google millions of dollars to put towards … surf wave pools”, she realised “renewables alone isn’t enough, it’s got to have more meaning behind it.” Heard then spent six months in Ethiopia with a UNHCR program that installed solar minigrids and trained refugees in their design, build and management.

Back in Australia in late 2018, Heard launched Alinga to find more responsible and effective ways to bring energy to Indigenous communities. In addition to collaborating with Ekistica and Indigenous Energy Australia (below), Heard has applied for funding under the federal Regional and Remote Communities Reliability Fund – Microgrids to work with five WA communities. She is also a panelist on the Papua New Guinea Off Grid Technical Assessment Panel, part of the Australian government’s international Economic and Social Infrastructure Program (ESIP). Heard is also offering pro bono renewables support to an Indigenous social enterprise in Eumundi, on Queensland’s Sunshine Coast hinterland, and their café Deadly Espresso.

Heard has her eye on some of the big-picture issues around renewables in Indigenous communities. She’s concerned about projects that “drop a solar system in harsh, remote areas without setting aside money for parts or maintenance”—not only do Indigenous people not benefit from any transfer of knowledge, skills or profits, but it results in “rubbish scattered in remote areas, which can be toxic as well.” Heard is also worried by a bit of cowboy mentality in the renewables sector, where companies alert to funding opportunities may end up pushing weak feasibility studies on Indigenous and other groups, urging them to lease their land for renewable projects. “It’s not fair to offer money for something they don’t understand,” Heard says, “when their organisations and local advisors don’t have the knowledge and experience they need to make an informed decision.”

Indigenous Energy Australia (IEA) shares Heard’s focus on community engagement, incorporating local knowledge about weather cycles and animal behaviour into their process. One stage of the installation on the 200 kW Lockhart River solar project in the Cape York Peninsula (mentioned above, and coordinated by Australian Sustainable Energy) was deliberately delayed because the community’s elders knew it was going to rain. “And it did, so that was lucky,” said IEA CEO Michael Frangos. “Cost savings using 60,000-year-old knowledge—that was cool.”

Founded in 2017, IEA aims to combat climate change and improve Australian livelihoods, while demonstrating that ethical principles can create a commercially viable enterprise; they hope their business success will stimulate competition and innovation by other renewables firms. Their design process works to meet a community’s financial, environmental and social goals and focuses on the crossover between “the humanistic and the technical.” Nine out of 11 IEA affiliates are also Indigenous people from Australia, PNG and Fiji, and whether they’re working in vulnerable urban or remote areas, IEA’s projects are “hi-tech, low-spec” so they can access and develop local capacity and skills as much as possible. Quality and simplicity also ensure fewer breakdowns and avoid prolonged periods of ‘system black’ when parts or expertise are needed from outside.

In addition to these companies, Bunjil Energy, based in Melbourne, is the construction partner for Voltfarmer’s 4.85 MW solar farm on the Mornington Peninsula. Boya Energy in Western Australia has partnered with the Widi community to establish a solar and battery off-grid system. And finally, Territorian Dice Australia (and its suite of businesses) is 100% Indigenous owned and operated, and specialises in electrical contracting, smart and renewable energy and construction. Recent projects include taking three communities in Groote Eylandt completely off-grid with renewable tech.

We should point out one final, vital element in the Indigenous renewables ecosystem, no matter how big the project: partnerships. Renewable installations in Indigenous communities are complicated, and all technical, financial and cultural aspects must be addressed and carefully integrated. Examples include the 10 MW Northam Solar Farm in WA, where government body Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) was a co-equity investor with Noongar partner Bookitja, and the project was built by Carnegie Clean Energy. (IBA’s programs include a Renewable Energy Loan specifically developed for remote Indigenous communities that are reliant on diesel generators.) The Pilbara Meta Maya Regional Aboriginal Corporation went off-grid in 2015 through a project with Energy Made Clean, a Carnegie subsidiary: a 100 kW solar array with 75 kWh batteries in Wedgefield, Port Hedland. The Kurrawang Aboriginal Christian Community, of about 100 people, had a 30 kW solar system installed in April 2016 through a collaboration between Renew, Indigenous Community Volunteers, Zasco Solar and two philanthropic trusts (see Renew 136 for details—the system’s still going strong). And NSW’s Valley Centre is crowd-funding to establish a rolling solar fund for Indigenous communities seeking renewable power, where repayments from one group will fund the project of the next. Its first project is now powering homes in Brewarrina.

Ultimately, enabling renewable power in Indigenous communities presents a great opportunity for innovation and impact in Australia’s energy sector, while giving communities stability, economic opportunities, and logistical support to remain sustainably on country. Stand-alone renewable systems in remote areas have a solid business case, and the work of Indigenous-owned companies provides specific benefits around culture and equal opportunity. For Indigenous people to have a fair share of Australia’s renewable power, funders, developers, businesses, utilities and governments must invest in respectful, patient, generous community engagement and participation. Our First Nations cannot be left in the dark.

Resources:

Indigenous Energy Australia: indigenousenergyaustralia.com

Centre for Appropriate Technology (CfAT) Bushlight archive: cfat.org.au/bushlight-archive

Ekistica (CfAT’s commercial subsidiary): ekistica.com.au/case-studies

Further reading

DIY

DIY

Deleting the genset

If you have the need for the occasional use of a generator, then why not replace it with a much cleaner battery backup system instead? Lance Turner explains how.

Read more Renewable grid

Renewable grid

Is a floating solar boom about to begin?

Rob McCann investigates the world of floating solar energy systems.

Read more Electric vehicles

Electric vehicles

5B or not 5B

Large scale commercial solar farms can be time consuming to install and commission. Lance Turner looks at a company that has solved those issues.

Read more