Houses that think: Are smart homes really a smart idea?

Smart home technology is touted as the way of the future, helping to make life easier while reducing energy use. But is that really the case? Lance Turner investigates.

This article was first published in Issue 144 (July-Sept 2018) of Renew magazine.

In the last few years there has been ever-escalating enthusiasm for internet-connected appliances and devices, in the belief that connecting devices to the rest of the world can make life better for householders. However, there are both pros and cons of making your house smarter, and there are varying degrees of ‘smart’, so what level of automation should you be aiming for?

What is a smart home?

A smart home can be defined as one that contains one or more devices that collect data, store that data, either locally or in the ‘cloud’ (on an online server), and can act on that data to make decisions as to what they should do. The motivation behind adding smart devices is usually to improve comfort levels, safety and security of a home, and may also be to help an occupant with a disability.

Most likely, your home probably already contains at least one smart device, whether you realise it or not. For example, TVs usually have some level of network connectivity and many collect data, or can be programmed to. Other typical smart devices can be seen in List 1.

- Lights and controllers such as Philips Hue devices

- Light controllers and switches for existing non-smart lights and appliances, such as Sonoff controllers

- Alarm systems

- Smoke/CO alarms

- Fridges and other appliances

- TVs and media players

- Door and window locks

- Curtain and blind openers

- Garage door openers

- Security cameras

- Video intercoms

- Irrigation controllers

- Heating/cooling controllers, including smart thermostats and air conditioners with smart features like wi-fi

- Energy monitoring, including inverters, power diverters and similar systems

- Smart EV charging units, e.g. Zappi

- Smart meters (main house meter)

What are smart devices?

So what exactly makes a device ‘smart’? Firstly, as mentioned, it will need network connectivity. This may be via common wi-fi or wired ethernet, which allow it to connect to your existing home network directly, or it may be via one of a number of other protocols (see List 3). If the device uses one of these other protocols, then it will need to connect to an intermediate device, known as a hub or controller (see List 2). This hub then allows it to connect to the home network, and hence other devices in that network, as well as communicate with the wider internet.

Smart devices are usually also able to collect data and store it, either locally in the network or on a cloud server. They can usually also make decisions based on that data. For example, a smart window opener might close windows if it detects rain.

Smart devices can often also use external data sources to make decisions. For example, a smart irrigation controller, such as the Hydrawise unit, might use weather data from a weather service to decide if it should water the garden or not.

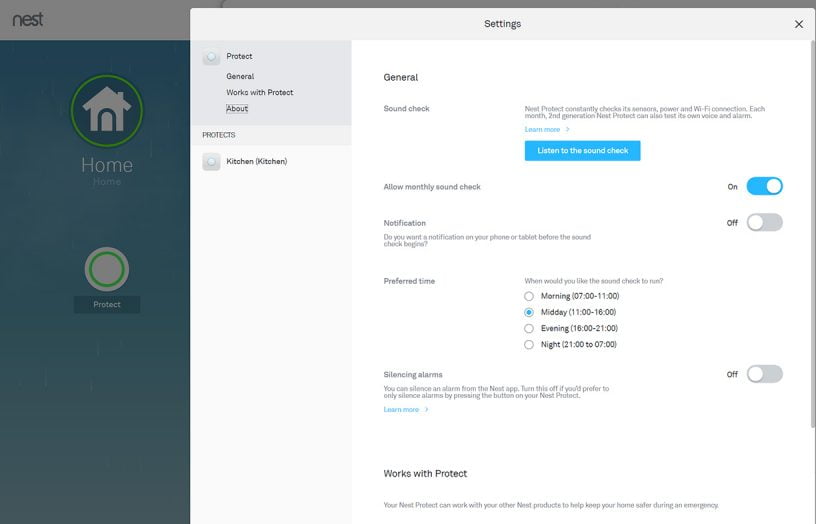

Many smart devices can also communicate with other smart devices in their own home network. For example, a smart smoke alarm, such as the Nest Protect unit, can cause a Nest camera to send you a photo when the alarm is triggered.

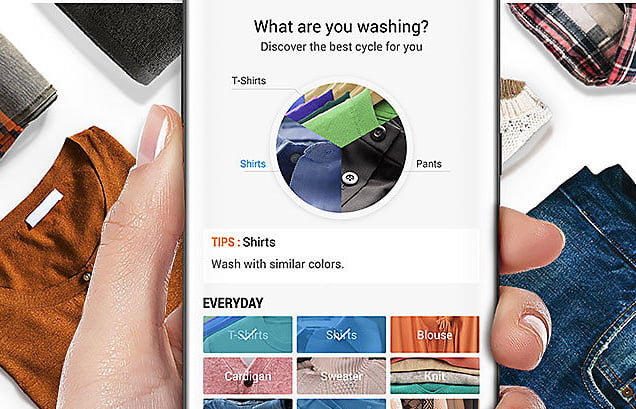

There’s more to smart devices than just hardware. To make a smart device useful, it must have a good human interface. This is usually a mobile app, with many devices also giving you the option of accessing your devices via a web page.

Some smart hubs go one better than a simple app and include a smart assistant as part of their own operating system. For example, the Amazon Echo and Echo Dot hubs use the Alexa interface, which not only speaks to you, but allows you to give voice commands, so you don’t need a mobile device to control lights or appliances. Other popular hubs include Google Home, which uses Google Assistant, and Apple HomePod (a smart speaker and hub combined), which uses Siri combined with the Home app.

- Philips Hue system

- Samsung SmartThings

- Apple Homekit

- Amazon Echo and Echo Dot

- Google Home

- Nest

- Vera Edge and Vera Plus

- Wink and Wink 2

In the past it has been difficult to get smart devices to play well with others. Each manufacturer (e.g. Amazon, Google and Apple) has their own ‘ecosystem’. An ecosystem describes devices that can all work together, such as all devices that are Apple Homekit compatible. They may use different communication methods, such as wi-fi and Bluetooth, but they present their data to the network in an understandable way. Devices that work in one system may not work in another, but cross-compatibility has been improving. Smart devices generally list the ecosystems they are compatible with and some smart hubs will talk to devices from different suppliers, with the hub acting as interpreter between devices. Despite this, compatibility issues still remain, but this should continue to lessen over time.

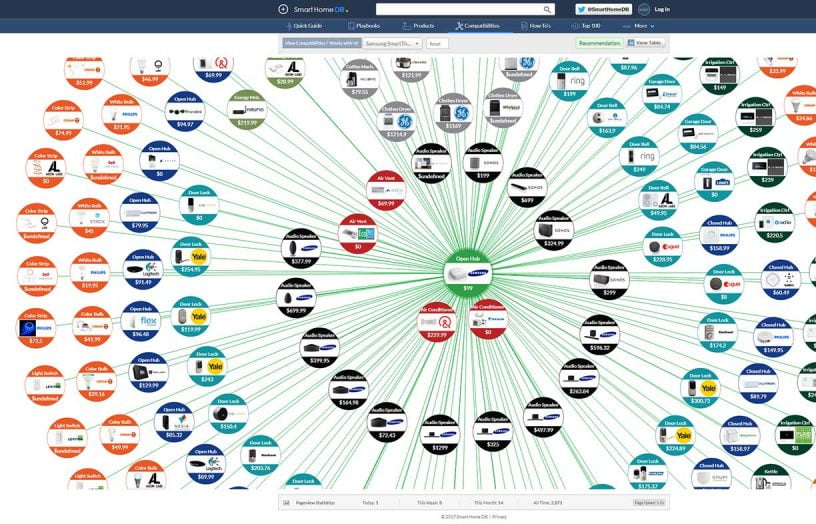

There are a vast array of smart home devices available, and this changes constantly, so it’s not realistic to provide a static list as to what devices are compatible with what. However, there are now online databases, such as www.smarthomedb.com, which provide comprehensive compatibility lists for just about every device you can think of.

One term often heard in relation to smart homes is IoT, or the Internet of Things. This is a broad term that encompasses all objects and devices connected to the internet that can be uniquely identified and have the ability to exchange data, whether it’s a smart TV, a lighting system, security camera, a sensor, an industrial machine, a vehicle or even a networked device you have assembled yourself, such as a media player built from a single-board computer such as a Raspberry Pi.

Even if you have smart devices using different ecosystems (and no hub to allow cross-compatibility), there is a way to make them talk to each other. Many smart devices have the ability to operate with cloud services such as If This, Then That (IFTTT). This and similar services enable you to write ‘recipes’ that allow devices from different ecosystems to all talk to each other, increasing automation flexibility. For example, you might have a simple web-connected light sensor that, when it senses darkness, triggers an IFTTT recipe that then turns on the smart security lights at your home. Or you can trigger an email to be sent when a particular event has occurred. For more information see Wikipedia or check out the IFTTT website.

- Wi-fi

- Bluetooth

- Z-wave

- Zigbee

- Ethernet (including ethernet over power)

- Thread

- KNX (open protocol, decentralised system)

- Infrared (usually devices like remotes)

- Mobile network (4G)

Real improvements

Although many smart devices might be thought of as simply gimmicks (and many certainly are!), in some cases, the smart version of a common device can be a huge improvement.

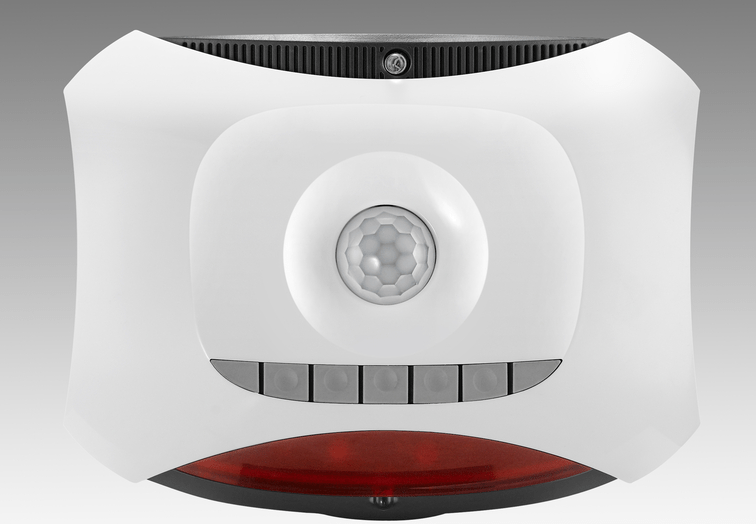

One example is the Nest Protect smoke alarm. This device not only detects smoke, but carbon monoxide (CO) as well. Further, instead of just sounding an alarm when it detects smoke, it talks to you about what has been detected and which room (when there are multiple networked Protects). It also features a ring of LEDs that show its status, glowing green when all is well, yellow when it has detected a problem and red when it believes the problem has reached a dangerous level. It also includes a motion sensor, so it can tell when you have left the house (or it can detect this depending on the location of your mobile phone) and it can message you if a problem occurs. It can even talk to Nest security cameras, which can send you images of the area in question if you are away from the house.

Compare this to a regular smoke alarm, which just sounds an alarm when it detects an issue, even if it is a false alarm caused by insects or condensation at 3 am (the Nest Protect also has dual wavelength sensors to reduce false alarms).

Similar advantages apply to other smart devices. For example, a simple irrigation controller will water your garden whether it is raining or not, unless it has a separate moisture or rain sensor. But a smart controller can ask the weather service what the conditions are before it starts watering a possibly already very wet garden. This can save a great deal of water.

When it comes to renewable energy systems, there are also considerable advantages to be had when using smart devices rather than simpler units. For example, a smart EV charger can make use of energy when it is cheapest and can even stop charging if grid demand exceeds a particular threshold (which would have meant high prices).

There are indeed many ways that smart devices can help reduce running costs of a home while making life easier, but there are also many ways that they can make life more difficult.

Do we really need smart devices?

Concerns about smart devices fall into several areas, including technical, social, financial and sustainability. Many of the concerns listed below fall into more than one of these areas, so we haven’t separated them out.

A primary concern is that of added complexity. What about when things go wrong? Having a bunch of smart devices refusing to work together because of a network or setup issue can be frustrating and time-consuming, and more hassle than it’s worth.

Another issue is that network errors and internet connection dropouts can mean things don’t happen as expected. Some devices are designed to get around such issues (for example, some security cameras also have on-board SD card storage in case of connection failure).

Socially, there is the valid position that allowing devices to do too much of our thinking for us can make us less capable when things don’t work, although this concern can be applied to technology generally, not just smart home devices. We need to ask ourselves: do we really need to be surrounded by smart devices in order to achieve energy savings?

Also of concern is security—a home with many devices connected to the internet is only as secure as the weakest of those devices. There have been cases of smart devices, including ubiquitous devices such as internet modems, being compromised. This isn’t helped when smart device owners fail to change default usernames and passwords to something more secure!

Further, data collected by smart devices has made its way into the public domain, potentially compromising the security of those it belongs to. Data stored in the cloud is only as safe as the security of the servers it is stored on—you are placing all your faith in the cloud service provider to keep that data secure.

And then there is the issue of smart device malfunction. A recent example saw an Amazon Echo device, through a series of misinterpretations of a couple’s private conversation, record that conversation and send it to someone in their contacts list. Amazon has addressed this issue, but clearly voice command systems have a way to go.

Financially, there are also some potentially hidden costs of having smart connected homes. For example, some devices are limited in function when used with the free version of the cloud service; a paid subscription is needed to unlock full functionality—and there’s no guarantee that subscription costs won’t increase considerably over time. If you stop paying for the subscription, your devices may become useless or less effective. Given that most of these services are hosted outside Australia and New Zealand, there is not much legally that subscribers can do if this occurs.

Other hidden costs, such as battery replacements, can impose both a financial and environmental burden.

Sustainability issues

An environmental cost that is often overlooked is the increased energy use in the home by having so many extra small devices connected and running 24/7. While each device may have a small energy consumption, having potentially dozens of such devices can add up. This ‘vampire’ power consumption has been written about elsewhere, such as here, and while the energy use is small and can be offset by savings made elsewhere, it is not something that should be ignored.

The other hidden environmental cost of smart homes is not found in the home itself, but rather in the cloud, where servers already suck up huge amounts of energy storing the vast quantities of data generated by millions of smart homes across the globe.

Although there are energy reductions to be gained in some cases by the use of smart systems, there is more to sustainability than just reduced energy use.

For a start, more devices means more e-waste, which needs to be recycled. If the manufacturer doesn’t have a recycling scheme for the products they produce (most don’t), then you are reliant on e-waste recycling schemes, which may mean the e-waste is shipped off-shore.

Each device also carries an embodied energy cost—will the energy it saves over its lifespan exceed the energy used to make and recycle it? In reality, it’s almost impossible to know this as manufacturers generally don’t have full life cycle analysis figures available for specific devices.

Another issue is the lack of interoperability between devices from different manufacturers, which can mean that systems may end up being replaced rather than upgraded or added to. Services such as IFTTT can help in this regard, but ultimately a smart home will generally perform better if all devices are from the same or compatible ecosystems.

The same issue can occur if the company that made your smart devices disappears. If this happens, odds are that the cloud storage service they provided may also disappear, and if there is no compatible alternative you can end up with a house full of useless devices, as well as losing your collected data.

Also along these lines is the issue of long-term compatibility, as protocols can change or fall out of favour. If devices can’t be updated with new firmware, they may have limited operability in the future. To avoid this, try to select devices from well-established manufacturers rather than newcomers that use odd or proprietary protocols and/or data formatting.

While it may seem odd, in some instances smart devices may use more energy than the devices they replace. One example is smart lighting, where smart LED lights can use more on standby than when running. An interesting article on one such case can be found here.

Some devices need lots of batteries, such as the Nest smoke alarm battery model, but like this device, many have settings that can be tweaked to maximise battery life. However, they will still need regular battery changes, usually every year or so, which adds to waste and resource use.

A recent study done by RMIT’s Centre for Urban Research showed that not only do many people have trouble installing smart devices and getting them working properly, but that the devices also often don’t result in energy consumption reductions, and may in fact increase energy use—for example, by allowing homeowners to turn on heating and cooling from work before they get home, increasing the daily runtime of such devices. For the full report and the report summary, which make interesting reading, go here.

What smart devices can do for you

All that aside, some smart or semi-smart devices can save considerable amounts of energy and greenhouse gas emissions if used correctly.

A good example is a smart thermostat. It is easy to leave home and forget to turn the heating or air conditioning off—most people have done it on occasion. A smart thermostat can be aware of whether there is anyone home and make the decision to turn the heating or cooling off or down, potentially saving a large amount of energy. The same can apply to lighting systems, which can turn lights off when you have left the room.

Devices such as automatic window openers can open and close windows depending on outdoor and indoor temperatures, as well as weather predictions, taking advantage of cooling breezes to reduce indoor temperatures even if you are not at home—but only if they also shut off the air conditioning.

Even devices that are not inherently smart can be used to save you energy by simply automating a particular task. A good example of this is a solar power diverter. Although they can be smart devices, many are not and simply divert power based on the excess energy being generated by the solar system. This allows PV-generated power to heat water rather than being sent to the grid, offsetting expensive grid power and reducing water heating costs considerably, especially in the sunnier months. You could use a simple timer in place of a diverter, but the timer would run regardless of the excess solar being generated, heating water from possibly higher tariffs in the middle of the day. We included a list of such diverters in our Efficient Hot Water Buyers Guide in Renew 139.

Similarly, some electric vehicle chargers, such as the MyEnergi Zappi, are capable of diverting excess PV-generated electricity to charge your electric car.

Another potential plus for smart devices and appliances can be in helping people with physical disabilities to control aspects of their home that they otherwise wouldn’t be able to, such as opening high windows, putting blinds up and down, or providing an improved sense of safety by allowing family members to monitor an occupant’s welfare or the conditions in the home remotely.

A manual component

Not all smart devices have to be in total control. You can use smart monitoring systems to provide you appropriate information to allow you to take actions that help reduce energy use. An example might be to monitor the outdoor temperature to alert you once a cool change has come through so that air conditioning can be turned off and windows opened. Or a smart monitoring solution can help you find those electrical loads that are chewing up energy in the background or even help you pinpoint appliance faults.

Degrees of ‘smart’

While smart homes are generally those that have internet-connected devices that can work together, there are varying degrees of smartness.

A fully automated home may have a full set of sensors, controllers, switches and actuators (devices that make things happen mechanically, such as opening blinds and windows), with all of these devices collecting data for a central hub or data processing system making decisions on what should happen and when. Some devices may have a degree of autonomy as well.

Or a home may have some degree of smarts, with a few combined or independent systems. An example might be a home with some smart lighting controllers, smoke alarms and security cameras, all controlled by a smart hub, with a separate energy monitoring system. You don’t have to have compatible systems if you don’t need them to interact and are happy to have more than one interface to control them.

A still lower level of smarts might be a home that just has a few smart smoke detectors and a camera or two for security, with no automation except for a separate solar PV diverter which has one simple function—to divert power at the appropriate level of export. The diverter has no interaction with the rest of the smart devices, and indeed, the diverter may have very little true smarts of its own. The same can apply to the PV inverter and energy monitor—it will often be an independent system which has no connection to any other smart devices, other than using the same home network.

A non-smart home will generally be completely manual—a typical home before the smart home craze took off. It may contain an energy monitoring system or some basic security cameras, but there is no internet-based data collection and cloud storage.

How to use the data to best advantage?

While automation is one goal of the smart home, the other goal is information gathering. The more information you collect, the more useful it can be—if it is processed and collated into a usable form (this bit is important). There’s no point gathering vast amounts of data about your home and its operation unless you do something with it.

Fortunately, many devices include data processing and display to make that collected data useful. The web portals included with many solar inverter systems are a good example. They collect data in real time, but only show you what is most useful, such as the current conditions, accumulated energy flows and periodic totals. You don’t need to see or understand the many thousands of data points that are used to produce those numbers, all you need are the final figures themselves to help you pinpoint energy consumption issues or improve your generation utilisation.

Some services, such as carbonTRACK, are specifically tailored to sustainability of energy use, providing both hardware and software to enable you to improve your carbon footprint. The carbonTRACK hub (or you can use a Google Home if you already have one) collects data over time and the web dashboard and app present it in a usable way, enabling users to create schedules for appliance operation to maximise energy generation and storage (if installed).

There are a number of such services, and the capabilities of them change constantly as they all compete for more users. While having so many options provides flexibility, it means that the smart home market is quite confusing. Unfortunately, there is no simple way around that—the number of device and service providers is vast.

Deciding on which devices to go with and how far you want to smarten your home can be a daunting task, but my advice is to start small. Start by replacing a device that has reached the end of its useful life, such as a smoke alarm, light bulb or kitchen appliance, with a smart version, and see if the greater capabilities of the new device are worthwhile for you. Get a feel for the technology and see if you really want to spend time messing with settings and checking on your smart devices on a regular basis. You might find it too much trouble and decide a smart home or even some smart data gathering devices are just not worth the effort, or you may find the data very useful, with the potential to reduce energy bills and your carbon footprint. The only way to know is to try the technology!

This article was first published in Issue 144 (July-Sept 2018) of Renew magazine. Issue 144 has smart home technology and smart electric heating as its focus.

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Tradies and the transition

Do we need as many tradies for electrification as many think? Not if we are innovative, writes Alan Pears.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Double glazing on the (very) cheap

Do we need as many tradies for electrification as many think? Not if we are innovative, writes Alan Pears.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Ditching the shower fan

By fitting a lid on the shower, exhaust fans are not needed when showering. John Rogers describes this simple retrofit, using both a commercial product and a great looking DIY version.

Read more