How green are compostable plastics?

Increasingly, some varieties of plastic are marketed as more sustainable. But are they as good as they seem?

Plastic is a miracle of modern science. It is cheap to produce, can be used in nearly endless applications and is incredibly durable. But for those of us who care about protecting our environment, plastic—especially the single-use variety—can feel like the enemy. The proliferation of biodegradable plastics in consumer goods may seem to resolve this tension, providing a guilt-free way to use plastic in our daily lives. But biodegradables also present many challenges in terms of sustainability, and in some cases may exacerbate problems caused by our single-use culture. As responsible consumers, is there a place for these materials in our lives?

Compostable vs biodegradable

To understand the potential benefits and pitfalls of new types of plastic, we first need to dig into the chemistry behind these materials. All types of plastic are polymers—a long chain of repeating carbon-based molecules tightly bound together. This molecular structure means that plastic is extremely durable, taking hundreds of years to break down in the environment. This is both what makes plastic so useful, and—in light of the 3 million tonnes of plastic consumed every year in Australia alone and the 40% of it that is used only once—also what makes it such a problem.

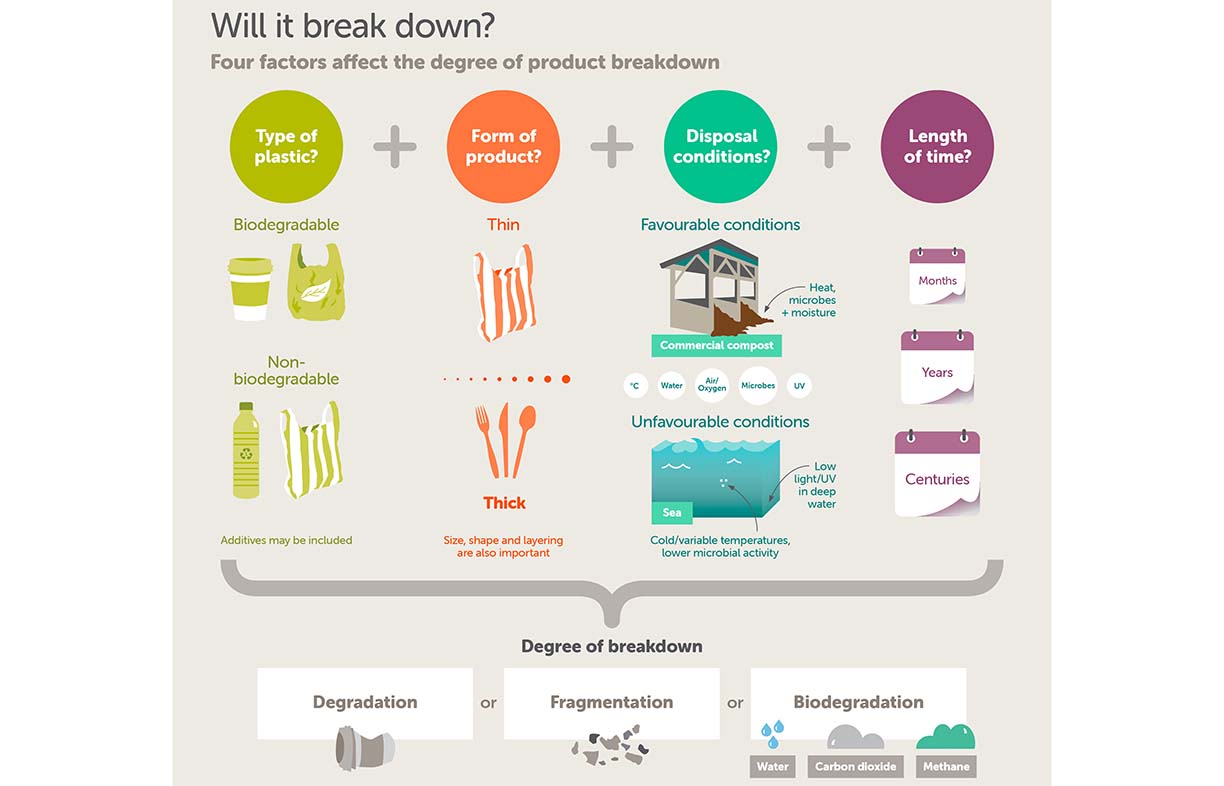

Technically, all plastic is biodegradable—eventually. Plastic, like other materials, will be broken down by microbes or fungi in the environment into CO2 and biomass if given enough time, even if that takes thousands of years. But what we generally call ‘biodegradable plastic’ is designed specifically to give microbes more opportunities to break the material down faster, on time scales of months rather than centuries.

Since biodegradable is a broad concept, ‘compostable plastic’ is a more accurate term for what we want to talk about in this article, according to Mike Williams, a CSIRO researcher.

“Compostable plastic is a better term, because there are rules around it,” Mike says. “If you say a bag is compostable, there’s criteria it must meet. If you say a bag is biodegradable, most people would think it breaks down, but it doesn’t specify how long that will take. It will biodegrade, but maybe the next lot of dinosaurs will see that happen.”

“Biodegradable as a label or as a claim is meaningless because it doesn’t tell you whether the biodegradation actually happens or under what circumstances it happens, it doesn’t tell you the byproducts, it doesn’t tell you anything,” says Australasian Bioplastics Association (ABA) president Rowan Williams.

Most compostable plastic sold in Australia is meant to be broken down in an industrial composter. This plastic generally adheres to Australian Standard 4736, a voluntary standard that is certified by ABA’s third-party auditors, which requires that industrial compostable plastics meet certain requirements:

- A minimum of 90% biodegradation of plastic materials within 180 days in compost

- A minimum of 90% of plastic materials should disintegrate into less than 2 mm pieces in compost within 12 weeks

- There should be no toxic effect from the resulting compost on plants and earthworms

- Hazardous substances such as heavy metals should not be present above the maximum allowed levels

- Plastic materials should contain more than 50% organic materials.

There are similar requirements for Australian Standard 5810, which governs plastics that can be composted at home. Not all compostable products are marked with the standard number, but most should have a green seedling leaf on them and a symbol indicating whether it’s appropriate to compost them at home or industrially.

What are the drawbacks of compostable plastic?

It’s important to understand the potential issues compostable plastic presents before we can develop ideas about successful applications. It’s already common to encounter compostable plastic in our daily lives, but many of us still don’t know how to use it or dispose of it correctly. This plastic is designed to be industrially composted, and yet there is little information given to consumers who may encounter it about how to make that happen.

Since it is designed for industrial composting, it should be appropriate to put compostable plastic into a green bin with food waste to be composted—however, compostable plastic is still considered a contaminant by the EPA in some states, like New South Wales. In practice, most composters will accept plastic if they can see it’s clearly marked as compostable.

Because of this lack of clarity around disposal, it’s likely that some, if not most compostable plastic in Australia will end up either in landfill or as pollution in our environment. When it makes it to landfill, compostable plastic is just as harmful as traditional plastic. And as litter in our natural environments, it can last years.

A 2019 study by marine biologist Richard Thompson and Imogen Napper at University of Plymouth in England, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, exposed biodegradable, oxo-degradable and compostable plastic shopping bags to a variety of environments, including shallow seawater and soil. After three years in soil, the oxo-degradable bags and the biodegradable bag were all able to carry a load of groceries. The compostable bag was unable to carry a load of groceries, but still hadn’t entirely deteriorated.

“The overarching conclusion was that you should not rely on any of these materials to degrade rapidly across a range of different natural environments,” Richard says.

Compostable plastic can also undermine other waste-reduction efforts. If it ends up mixed with recyclable plastic, it can compromise recycled plastic’s durability, essentially adding a “self-destruct” feature, Richard says. And even if correctly sorted into industrial composting, plastic can take longer to degrade than other compostable materials, leaving microplastics in the compost.

“Large industrial composting facilities usually work to process their material in two to three months. Even if the compostable plastic conforms to the Australian standard, it may not completely degrade in that time,” says Mike. “Within the standard there can be less than 10 per cent residual material left after 180 days.” As a result, composters who accept compostable plastic may find “they have residual plastic in their final product.”

Compostable plastic can also compromise what makes standard plastic so desirable: it is more expensive for consumers, and, by definition, is not as durable.

“If you’re [a supermarket], you don’t want people to take their meat tray home and have it fall apart,” Mike says.

Ultimately, common compostable plastic products like coffee cups still encourage people to use them once and throw them out. And that isn’t sustainable, regardless of how quickly they decompose.

What are the potential benefits of compostable plastic?

There are some circumstances in which compostable plastic could work very well. Richard says that situations in which one entity has control of the entire life cycle of a product could offer a good application. At a sports stadium or a music festival, a hamburger wrapper would only be needed for a short period of time. The material would be chosen by the organisers who can also make sure that wrapping ends up in the correct composting stream along with the food waste. This kind of closed system—from use to disposal—is crucial to the success of a product like this.

“For an almost identical hamburger wrapper served at a take-away restaurant, there’s very little guarantee that the wrapping will reach the right waste stream, especially if the consumer is not even informed about the necessary disposal pathway,” Richard says.

Compostable plastic could also be useful in limiting food waste going to landfill, by encouraging people to bag their food scraps and send them to an industrial composter (as long as that composter accepts the bags).

“If 30% to 40% of domestic waste going to landfill is made up of food waste, which will produce methane, then doing everything possible to reduce this drastically is important,” Mike says. “Encouraging people to collect food waste for green bin collection by distributing certified compostable bags to ratepayers will do this, as well as reducing contamination in the composting stream from non-compostable plastics used to store food waste.”

Another application involves scenarios in which plastic is highly likely to end up in the environment. ’Ghost fishing’, in which lost nets or traps continue to catch fish, is a huge problem in marine environments. Making fishing nets out of compostable plastic is unworkable, as it will undermine their longevity and effectiveness. But Richard says that compostable plastic cable ties on lobster pots, for example, could be a solution.

“If the pot was lost at sea, those ties would degrade in a season and the pot would no longer function to catch lobster,” he says. As long as the fisherman holds onto the pot, the cable ties can be renewed the next season to make it functional again.

Mulch film—plastic laid across the top of soil in industrial agriculture to limit weeds and control soil temperature and moisture—is another, more mainstream application for compostable plastic, Rowan says. Using compostable plastic for this purpose could prevent traditional plastic from breaking down into microplastics in the soil.

Mike believes that there may be wider applications for compostable plastics in replacing plastic that could be contaminated with food. Where it’s necessary to package food with plastic, that plastic can become contaminated and unable to be recycled. If it could be composted along with food waste, that might make a real impact on overall packaging waste. But Mike is careful to point out that this would require industrial composting—few of us have home compost heaps big enough to accommodate all our plastic packaging. And home composting, as it isn’t aerated as regularly as industrial compost and does not reach the same high temperatures, is not as effective at breaking down materials.

However, there may be some applications for home composting plastics as well. Tea bags and coffee pods that contain plastic are already often mixed into home compost heaps (though clearly it would be best to avoid putting plastic in tea bags or using single-use coffee pods in the first place).

“It’s a small amount of plastic and making sure that is degradable could be a good thing,” Richard says.

Overall, it’s all about making sure that the full life cycle of a product is taken into account, and that there is a high likelihood it will end up in the proper waste stream. Otherwise, compostable plastic simply adds more unsustainable products into our environment.

What do we do with compostable plastic in Australia?

As mentioned above, there is no one answer for what consumers in Australia can or can’t do with compostable plastic. While some states consider all compostable plastic a contaminant in green bins, some individual councils allow compostable plastic of all kinds in their organic waste streams. Adelaide’s City of Onkaparinga accepts many kinds of compostable products in their green waste bins, including cutlery and bags. Other councils in the same city, like Adelaide’s City of Marion, accept only compostable bags. Some councils, like Darebin in Melbourne, accept no compostable plastic at all. Unfortunately, many councils do not currently accept any food waste. New South Wales has the best figures in the country, with 35% of councils accepting food scraps in green bins, according to a 2018 report from the Australian Packaging Covenant Organisation (APCO).

Given this patchwork system of regulations, the most effective way to responsibly dispose of compostable plastic is to talk to your local council or check on their website to see what they accept.

Adopting compostable plastic responsibly

How do we address the many issues with compostable plastic so we can take advantage of the benefits? The two keys are public education and responsible design.

“Consumer engagement and education is massive,” Mike says. Councils, state governments and organisations like ABA dedicating themselves to educating the public about how to use and dispose of compostable plastics can go a long way towards solving the problems we currently face with these products.

Individual producers of compostable products need to take responsibility as well. Products with no clear end-of-life waste stream shouldn’t be produced.

“It’s really important at the design stage that you recognise: what does the consumer or the end user do at the end of the product’s life? How is it going to be disposed of?” Richard says.

Experts agree on the real solution to these problems: stop using so much plastic, especially for single-use purposes.

“The best thing to do is not use plastic in the first place—avoid it where you can,” Mike says. “Where you do need to use it, reduce the amount.”

More on alternative plastics

Bioplastics

The term ’bioplastic’ is commonly used to describe plastic made from organic materials like plants, rather than fossil fuels. There are a variety of bioplastic materials in production. These include plastic made from a combination of starch and biodegradable polyester, cellulose-based plastic, protein-based plastic and aliphatic biopolyesters, often produced from corn or dextrose. It’s important to note that these materials are only biodegradable if they have been designed to be.

The sustainability of these materials varies. Much like biofuels, bioplastics require land dedicated to growing crops to produce plastic rather than food, can contribute to deforestation and may involve the use of pesticides. Many bioplastic products on the market are single-use items that can be just as harmful to the planet as plastics made from traditional carbon sources. Because of these issues, the experts we spoke to say the most sustainable carbon source for new plastics is old plastics, in the form of recycling.

Oxo-degradable plastics

Oxo-degradable plastic (often just called degradable plastic) includes a catalyst which allows it to degrade when introduced to certain temperatures, air or light for a period of time, with the intention that it will degrade faster in landfill or in the environment, where most plastic ends up. This plastic is usually not made from plant-based carbon, and it is specifically not biodegradable. Its degradation process is abiotic, occurring without the help of bacteria or fungi. Some plastic is also marketed as oxo-biodegradable. These products claim to degrade both biologically and abiotically, but most likely take longer to degrade than compostable plastics and may generate microplastics.

Case study: Raising the bar

When Ellen Burns started her Ballarat-based healthy snack bar company, We Bar None, she wanted to apply her dedication to sustainability not just to the product, but to the packaging as well. She began looking for home-compostable packaging for her bars immediately. The process was more difficult than she expected.

“I looked into a few suppliers that claimed they had compostable packaging,” Ellen says. “But I found out their adhesives were made from fossil fuels and they weren’t certified compostable.”

Finally, after an 18-month search, Ellen stumbled upon PA Packaging Solutions, the first Australian company to provide certified home-compostable packaging to businesses. Ellen began working with them and inadvertently became the first business in Victoria, and the third in the whole country, to use home-compostable packaging.

When Ellen first began using the compostable packaging, she was keen to test it out herself. She buried some of the packaging in plain dirt in her yard in chilly Ballarat and found it was gone in under two months. Now, she puts the packaging in her own home compost all the time. But she hasn’t had any issue with the packaging—which has a 12-month guarantee, the same as her bars’ use-by date—failing on her. Even samples she kept of the first bars she received with the compostable packaging nearly two years ago still have their packaging fully intact.

In order to inform her customers about how to dispose of the packaging, Ellen has printed instructions on the wrappers. She also focuses on selling to stockists who emphasise sustainability to customers, including a few who sell no plastic products, and working with initiatives like Zero Waste Victoria to encourage changing the culture around single-use plastic.

Ellen hopes that other businesses will see that using home-compostable packaging is possible and affordable.

“I was happy to be the first business in Victoria to use home-compostable packaging, but I am surprised to still be the only business in Victoria after two years,” she says.

Ellen says she has heard from several large Australian businesses who are currently trialling using home-compostable packaging on their products, but it’s more challenging to make that shift at a large company where many people are involved in decision-making. Still, Ellen looks forward to no longer being on the cutting-edge.

Resources:

Plastic Free July has a wealth of resources to help you reduce your use of single-use plastic, and you can take the challenge this July to do just that. www.plasticfreejuly.org

Further reading

Reuse & recycling

Reuse & recycling

Community eco hub

Nathan Scolaro spends 15 minutes with Stuart Wilson and Michael McGarvie from the Ecological Justice Hub in Brunswick, Melbourne.

Read more Reuse & recycling

Reuse & recycling

Recycled hydronic heat

Renew’s sustainability researcher Rachel Goldlust gives us a view of and from the Salvage Yard.

Read more Reuse & recycling

Reuse & recycling

The future of packaging

Packaging comes with just about everything we consume, with far-reaching implications for us and the planet. Jane Hone asks how we can get a handle on it.

Read more