Warnings from the EU and UK energy crisis

Alan Pears updates us on the pending energy crisis in many parts of the world, discusses the future of big batteries, and looks at an often overlooked form of housing.

EU and UK energy prices are spiking. Shortages and blackouts seem likely. While both Vladimir Putin and COVID can take some responsibility, this crisis isn’t just because of the pandemic and/or because UK and EU governments have allowed themselves to become dependent on Russian gas.

Business regulators and central banks are also applying pressure, and few investors are prepared to invest in anything to do with fossil fuels: it’s risky, even though short-term prices have spiked. When the conservative International Energy Agency’s climate scenario requires no new fossil fuel development from 2021 and investors and consumers are facing the lived experience of increasingly extreme weather, the business environment changes.

But another driver of the EU crisis—and similar spiking prices around the world—is that governments have failed to deliver enough investment and activity in energy efficiency, energy storage, demand management, electricity transport/transmission and renewable energy supply. Shortages often occur in extreme weather, when thermal performance of buildings and appliance efficiency matter a lot: a 6-Star house needs about a third as much heat on a cold, cloudy winter day as a 2-Star house. A high efficiency heat pump replacing traditional electric or gas heating amplifies overall heating energy savings to 90%.

Energy efficiency also frees up capital for the energy transition, lowers energy costs and delivers extra benefits such as health and business productivity. Flexible, efficient manufacturing processes also matter a lot: they can be managed optimally with smart data analytics.

Here in Australia, state and territory governments have recognised the need for investor certainty in renewable energy through auctions rewarded by long-term renewable energy and battery contracts. The Renewable Energy Target provides a useful lesson. It created a market for certificates that provided some certainty. Indeed, REC prices had slowly declined to around $30 until the Abbott government attempted to kill off the scheme. When a revised but seemingly ambitious target was eventually salvaged from the madness, the price spiked to over $85. Businesses responded to this price signal by dramatically increasing investment, bringing the price back down to under $30 for most of 2021—and easily meeting the target. This reflects the significance of certainty and forecast supply-demand concerns on market prices.

We should be applying these lessons to all aspects of the energy system, and to carbon emissions. How can our governments ignore a situation where businesses and households are rejecting investments that deliver carbon abatement at minus $100 or better, while they rush to buy carbon offsets at $50/tonne or more? This is serious, chronic market failure. In Europe carbon prices have exceeded AU$100. Yet their economies, like Australia’s, have enormous abatement opportunities with negative cost. These high prices reflect the market’s judgement—which is often uninformed—and ots lack of confidence that governments will act to overcome complex barriers.

On the flip side, when business does eventually focus on negative and low-cost abatement options, we may well see carbon prices fall—or be able to cut emissions much more at the same cost. We need to keep driving down the costs of an integrated, reliable renewable energy system. A lot of the low hanging fruit is demand-side energy action. For example, the E3 appliance efficiency program was recently reported to be avoiding carbon at minus $200/tonne in a recent review, and there is enormous potential for industrial efficiency improvement. Where are the multi-billion dollar programs and regulatory support structures to drive these activities harder?

Caravans, our invisible households

We have over 600,000 caravans in Australia. They may be plugged in at a caravan park, or used as extra accommodation in a backyard. And while they may only be occupied part-time, many use electricity for most of the year. So how much energy do they use? Who knows?

However, we do know a few things: caravans have little or no insulation—even new models often have as little as 20 mm of insulation. They also often have uninsulated annexes, and are inevitably draughty. Staying comfortable in them can therefore use a lot of energy. In addition, they have incredibly inefficient three-way fridges that can run on LPG, low voltage or mains electricity. These use three to five times as much electricity as a modern family fridge when operating on electricity. Many now also have hot water services for showers and washing machines. While there is increasing interest in PV systems, these are often small, and may not operate when the caravan is plugged in at a park.

Towing vans can use a lot of extra fuel. If you own a big 4WD to tow your caravan, it’ll use more fuel than a smaller car for everyday travel when not towing. Maybe your main home will use a lot less energy while you are away—if it’s unoccupied and you switch most appliances and the hot water service off.

The energy network operator revolution

Last August I attended a webinar hosted by Energy Consumers Australia, and found that it offered some pleasant surprises. The opening speaker—Nicola Heppenstall, a social researcher and Executive Director of the Inight Centre—had actually talked to people in bushfire-affected areas. The insights she had gained were disturbing, but consistent with my dealings with those people.

She was followed by two representatives of monopoly electricity networks covering fire-affected areas: Luke Jenner of Essential Energy and Thomas Hallam of AusNet Services. It was clear that both had confronted road-to-Damascus moments: they had realised that their businesses were not about poles and wires, but about serving people. Both shared anecdotes about this: time spent carrying jerrycans of fuel to allow people to run generators for basic services, for example, or the challenges of explaining to the people of Mallacoota what a new community battery was going to do—and fending off criticisms of delays in installation. You can listen to the session at bit.ly/37ZTXZ4

Meanwhile, in a RenewEconomy podcast, the CEO of Ausgrid talked about their recognition that locating batteries near consumers maximised benefits for everyone. Network operators are also setting up companies that are separate from network regulation (eg SP Ausnet’s Mondo): they can engage in a wide range of activities and consumer engagement.

At the same time, interest in community batteries is increasing, but their economics are very sensitive to installation arrangements and energy market rules. A paper by Bruce Mountain and Kelly Burns from the Victoria Energy Policy Centre (bit.ly/3D94V9U) explores some of these issues.

Recent changes in market rules also make it more profitable for network operators to offer to take consumers off-grid where doing so is cheaper and more reliable than being on the grid. This approach has been pioneered in Western Australia.

After two decades of privatisation, operators are finally questioning their assumptions. It’s all getting very interesting.

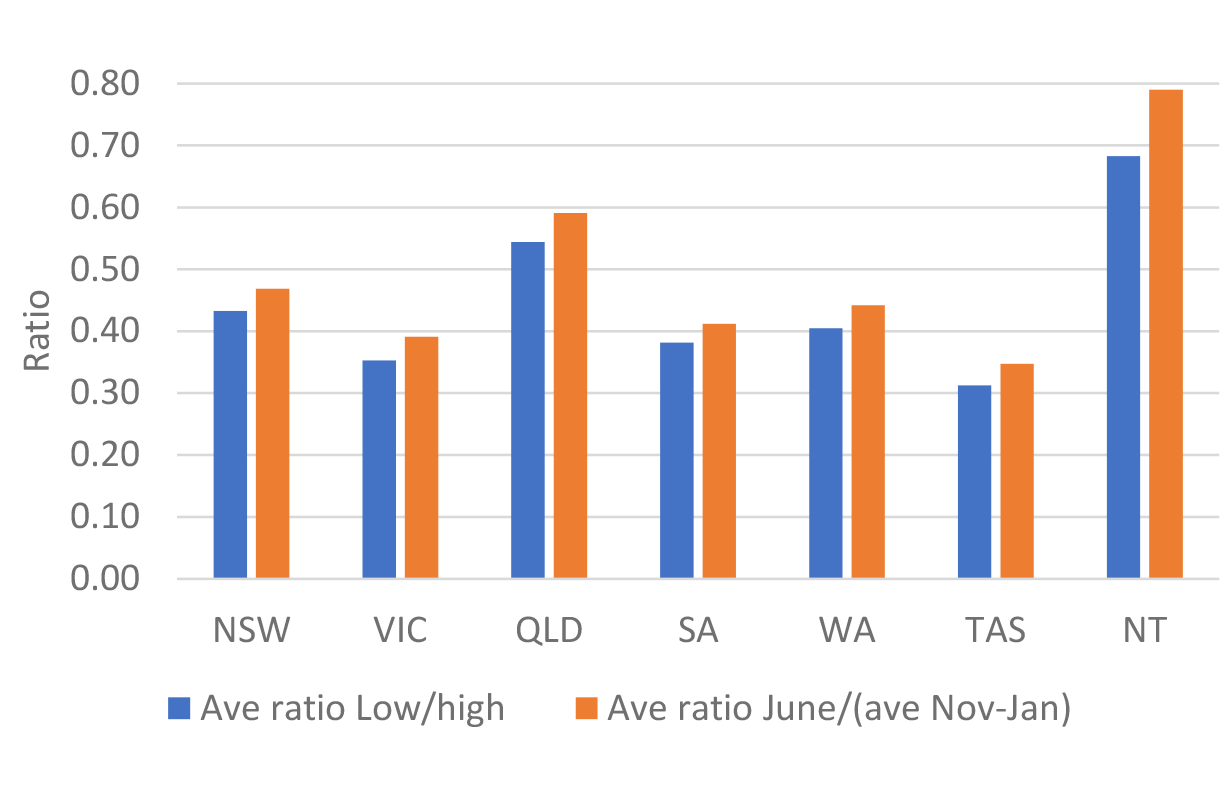

The seasonal energy challenge

What is a “net zero emission ready” home? Sure, it is becoming popular to install enough rooftop solar capacity to achieve annual net zero energy and emissions—but should this be our sole aim?

We need to think carefully about winter supply and demand in cooler climates. The heating of inefficient buildings by inefficient heaters using fossil gas and grid electricity is emerging as a major challenge. Our buildings leak heat like sieves, especially in cloudy, windy weather. In Victoria, our shift away from fossil gas toward reliance on solar energy creates problems in winter, when heating demand for both gas and electricity increases.

In Victoria, June average rooftop solar output is less than 40% of the average output over summer months, while residential and small-medium business gas use in July is five times summer demand. Significant amounts of gas are also used to generate electricity in winter—and local gas production is declining.

Aiming for “zero net emission/energy” over the year will not solve this problem: in fact, it could lead to excess renewable electricity in summer and shortages in winter. This is an increasing concern for governments, and an opportunity for the gas industry to push for more investment in gas supply—when we actually need to cut fossil gas consumption to decarbonise. There are many ways to address this challenge, but we need to focus on its subtleties, rather than on buzz phrases and simplistic “solutions”!

Further reading

Pears Report

Pears Report

Fossil fuels, efficiency and TVs

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more Climate change

Climate change

What we can learn from Spain’s response to heatwaves

As Australia heads into a summer set to be marked by climate change and El Niño, resilience to extreme heat is front of mind. Renew’s Policy and Advocacy Manager Rob McLeod reports on Spanish responses to heatwaves and the lessons for Australia.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Transmission and emissions

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more