May 2022 election—a new beginning for climate and energy policy?

Alan Pears shares his thoughts on what the election of a Labor government (or rather, the dumping of the LNP) means for climate action in Australia.

The election of a national Labor government offers a glimmer of hope that Australia may shift from pariah to participant in terms of global action to limit global heating. But there are no guarantees that our new government will act either fast or aggressively enough.

The recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports have stated that humans must not develop any more fossil-fuel resources. A more recent study (bit.ly/3NSeAGD) points out that this would still take us beyond 1.5 degrees of heating. It states that staying within a 1.5 °C carbon budget (a 50% probability) implies leaving almost 40% of “developed reserves” of fossil fuels unextracted. The International Energy Agency has pointed out that allowing existing fossil-fuel production capacity to reach its economic end of life would drive heating to 1.65 °C.

Clearly an effective response will be disruptive, a consequence of decades of ignoring scientific advice. The recent invasion of Ukraine, tragic as it is, provides a demonstration of what might be involved in such a response. On one hand, past inaction means Europeans now face high energy prices. On the other, strategies aimed at dramatically reducing dependence on fossil fuels are being implemented. They will improve Europe’s energy security and, in many cases, reduce energy costs.

Numerous studies (e.g. International Energy Agency, Climateworks) have shown that there is great potential for negative emissions and low-cost emission reduction. Repurposing subsidies and investment from fossil fuels can help to finance change. The economic, social and environmental impacts that result from less climate change—by avoiding or reducing its scale—offer enormous benefits.

In its 2021 discussion paper (bit.ly/bca-lobt), the Business Council of Australia (BCA) noted that:

- Over the next 50 years, unchecked climate change will shrink Australia’s economy by 6 %—a loss of $3.4 trillion and over 880,000 jobs; and

- Over the next 50 years action on climate change and choosing a net-zero economy will grow Australia’s economy by 2.6 %—a $680 billion increase and the creation of over 250,000 jobs.

The BCA’s support for strong emission-reduction targets and strengthening the industrial emissions safeguard scheme seem to reflect its recognition of these points.

There will be winners and losers. Those who act fast and take risks are likely to be winners. Those who fail to act, like recent Australian governments and many Australian businesses, can be confident they will be losers.

So the big question Australia faces now is whether our new government will have the courage, or be forced by crossbench politicians, to move fast enough. Also, will the Coalition confront reality and support strong Labor action? Liberal moderates have been ignored, and have paid the Teal price for their failure to shift the government. The federal National party must reposition itself. It has ignored concerns raised by state-level members: for example, last year the Victorian Nationals debated a motion to dissociate themselves from the federal party due to their differences on climate policy (see ab.co/3NT3MIp).

We live in very interesting times. Tough decisions must be made and governments must help affected communities to transition while reshaping our economy and managing the impacts of global heating.

How Australia killed improvements to industrial energy efficiency

Australia rates 22nd out of 25 countries for “industry action” in the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy’s (ACEEE) latest international energy-efficiency scorecard. Clearly we need stronger action.

This led me to review what happened in 2014 when the Abbott government shut down Energy Efficiency Opportunities (EEO), the industrial energy-efficiency program. I declare a conflict of interest: I was one of the developers of that program, and I worked on its introduction in operating industrial sites and with real-world businesses. It was widely recognised as world-best policy practice at the time. Many businesses gained multiple benefits, and not just energy savings.

The 2013 independent review of EEO, not available on the internet now, showed it was saving over $300 m annually, at a cost of -$95 per tonne of avoided carbon emissions and after just a few years of operation. Climateworks estimated the savings at $1.2 billion per year. The 2013 review recommended that the program should continue.

But the impact statement of the ideologically driven Office of Best Practice Regulation assumed that the ongoing program would deliver zero future savings. It is difficult to imagine how a program like EEO could deliver nothing after saving hundreds of millions of dollars annually in its first few years of operation.

The ongoing annual compliance costs of $17.7 m, spread over about 300 large businesses with multi-billion dollar budgets, outweighed OBPR’s “calculated” benefits of zero. It recommended that the program be shut down—consistent with the radical right-wing Abbott government and its extreme “economic fundamentalist” ideology.

This decision has undermined the implementation of effective industrial energy-efficiency policy for nearly a decade, costing industry and Australians billions of dollars and billions of tonnes of emissions, and hobbling our ability to be part of a low-carbon global future. Yet it has attracted little public debate.

Unfortunately, my recent work on industry energy-efficiency programs has shown that most of the lessons from a decade ago have been lost. Most Australian business is part of our climate and economic problems, not part of their solution.

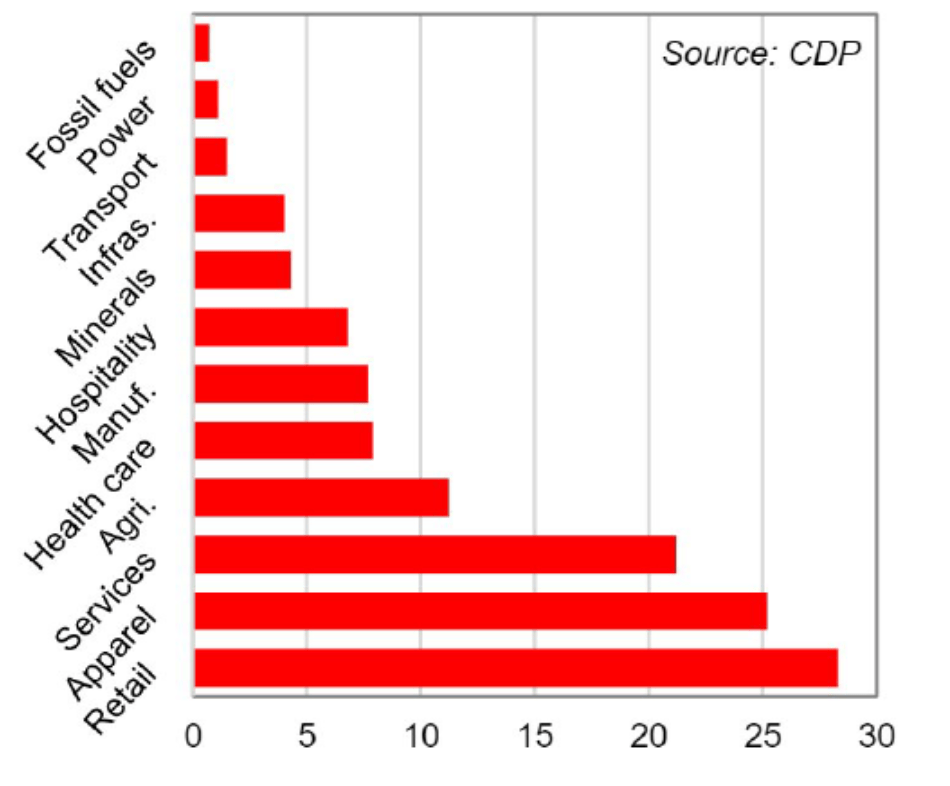

We need aggressive action. Strengthening the industry emission safeguard scheme is a small step in the right direction for major emission-intensive industries. But most Australian business is not covered by this scheme. Further, the Scope 1 and 2 emissions of most businesses (from the direct use of energy and activities they control and their purchased electricity) are a small proportion of overall emissions associated with their activities. As a recent Commonwealth Bank report showed, most of businesses’ climate impact results from upstream activity (producing inputs) and downstream activities (including operation of products and services). These Scope 3 emissions appear as financial costs built into inputs, and as operating costs for downstream businesses and households: they are hidden costs, or externalised ones that others outside the business pay.

Effective climate policy must require businesses to measure and report on significant Scope 3 emissions, and to work with suppliers and customers to reduce them.

Most businesses need help to understand and manage their emissions. This means training, finance and investment in smart real-time data analytics and flexible equipment. An updated EEO program including financing for concrete action would help. The public reporting of emissions and actions is also important to build accountability and motivate business managers.

Businesses also need help to identify the multiple benefits of climate action that are mostly ignored. These include reduced food and material waste, improved process reliability and productivity, better health and safety for staff, updated products with features valued by consumers, and many others. Reports on the benefits of energy efficiency by the IEA, Australian Alliance for Energy Productivity, Climateworks, the Green Building Council of Australia and many others document the enormous opportunities.

Our energy future in context

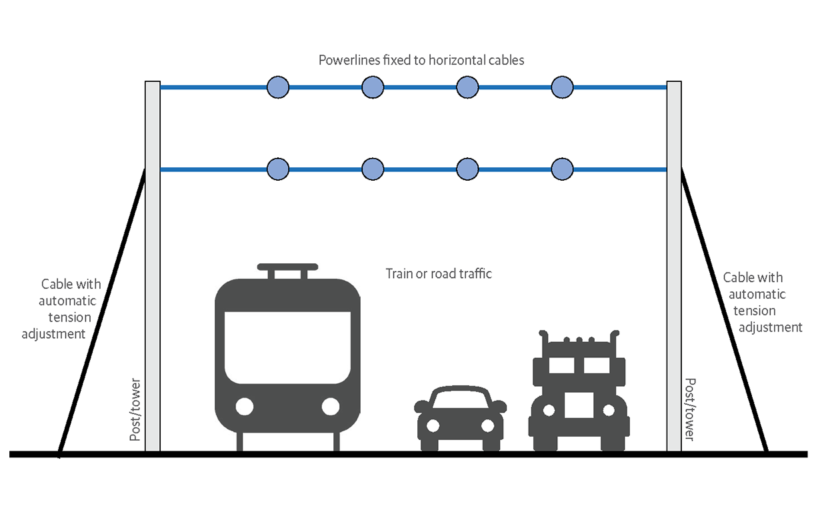

Former PM Malcolm Turnbull argues that we need lots of pumped hydro energy storage, while Andrew Blakers points out that we have many good sites for pumped hydro. The solar industry is aiming for even cheaper PV generation and the gas industry argues for hydrogen as our saviour.

Each option could play a useful role in Australia’s energy future, but we need to put energy into context. It is a ‘derived need’. No-one actually wants energy—or technology, for that matter—for its own sake. They want services they value—e.g. comfort, light, food preservation and entertainment—but even the idea of necessary services is unclear. People’s perceptions of the services they “need” are framed by their past experience, not what is possible.

Stationary energy (i.e. electricity and gas) comprises just a few percent of Australia’s GDP. The energy sector thinks it is very important, and the fragile energy system we have designed means many people think reliable energy is important. But it is just one of a number of critically important factors needed to maintain our quality of life and productivity.

Our capital investment in energy supply is also only a small proportion of total capital investment, so ‘rational’ economists and analysts who focus on energy issues are actually applying ‘bounded rationality’ by ignoring many other important drivers of behaviour. From a decision-maker’s perspective, it is often reasonable to treat energy as a minor issue as long as they can access the services they want.

How many people would prefer to return to a situation where they had to drive to a video store, hire a DVD and use a specialised video or DVD player to access home entertainment? How many people who have bought homes in regional areas would move back to cities to access work, now that remote working has evolved throughout the pandemic?

The energy sector struggles to grasp the implications of changes to what ‘consumers’ actually want (see for example bit.ly/3tBahra). This is partly because consumers often don’t clearly understand what services they want or what energy is required to deliver them.

It is an exciting and risky time, as our interpretation of energy needs evolves and the range of available technologies spreads across previously separate sectors. An electric car is a mobile battery. A home can generate and store electricity, and interact with the electricity grid. A thermally efficient home may need little or no heating or cooling. A mobile phone transforms our lives.

Further reading

Pears Report

Pears Report

Fossil fuels, efficiency and TVs

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more Climate change

Climate change

What we can learn from Spain’s response to heatwaves

As Australia heads into a summer set to be marked by climate change and El Niño, resilience to extreme heat is front of mind. Renew’s Policy and Advocacy Manager Rob McLeod reports on Spanish responses to heatwaves and the lessons for Australia.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Transmission and emissions

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more