Bruce the better motorhome

Dick Clarke tells the story of building his self-sufficient, leave-no-trace motorhome, drawing on renewable materials and energy.

I have been interested in exploring the wide brown/green/dry/wet/hot/cold land in more sustainable ways for about half a century. I love the bush in all its different forms and climate zones, and there is no better way to bond with it than to walk it in bare feet, to wake to its different moods, and to sweat or shiver as it sees fit.

While I love getting the dirt between my toes, realistic timeframes make walking to destinations all over the country a bit impractical. In the mid-1970s, I started mucking around with camping vehicles, and have tried all sorts of formats since, always pursuing lower ecological impact. We are now at the point where almost the entire self-sufficient ‘leave no trace’ set-up is resourced by renewable materials and energy, save for motive power—and a long-range EV is the next skittle on my hit list. But this story is about what we make things out of.

History

In the ’80s I was developing low-profile pop-tops and fiddling with early solar power for lighting and refrigeration. In the 2000s I was playing with converting lightweight SUV wagons into self-sufficient vehicles, successfully driving a Renault Koleos on several trips around and through Australia. It was completely self-sufficient except for using diesel locomotive power, proving you don’t need a big vehicle and large caravan for just two people.

In 2017 I built what might be the lightest, lowest profile and lowest drag coefficient, fully self-contained, two-berth motorhome in Australia, on the most efficient 4WD ute cab-chassis on the market at that time.

All operations are solar powered or renewable except motive power, which is an ‘efficient’ Renault diesel—but still a fossil burner. Nicknamed Dixi, the vehicle’s long-term average fuel consumption is 7.7 L/100 km, which is not bad for a motorhome complete with 150 litres of fresh water, 90 litres of grey water storage, shower and toilet. But the body was built like my A Class catamaran, or an America’s Cup yacht: synthetic foam sandwich with fibreglass and polyester resin—not very eco-friendly stuff, even if the lightweight result saves fuel. It has 750 W of PV on the roof, electric hot water, 12 V compressor fridge, and a metho stove, and is gas free.

Bruce the motorhome, grown in a paddock

Travelling with a family is more challenging—more bums means more seats. My next project, built during the 2020-21 lockdown, set out to solve the family-sized challenge.

I started with a 10-year-old six-seat dual cab-chassis Mercedes Sprinter as the base vehicle, and built a six-berth motorhome body on the back. But I also set the additional goal of building the whole thing out of the most renewable materials I could get hold of—everything should be grown in a paddock or a forest as much as possible. The family (adult children and grandchildren) decided to name it ‘Bruce Sprintstein’—we’re not sure of the ‘other’ Bruce’s connection to country, being born in the USA and all, but at least his politics are okay!

Ironically, Bruce the Sprinter was found in a wrecker’s yard at Port Stephens, having been a rescue vehicle in a Hunter Valley coal mine. I rescued it from that ignoble fate and turned it into a vehicle for helping families explore and understand country, and in so doing, love it and work to save it. I also discovered that while the mines claim to maintain their vehicles properly, at least in this case it was far from true. Never mind, it’s only money.

The goal of using all renewable materials was okay in the structure and joinery, but is a bit hard when it comes to things like fridges and electronics. So there are limits. Sometimes I had to look for the best performing and most robust available—the least worst options.

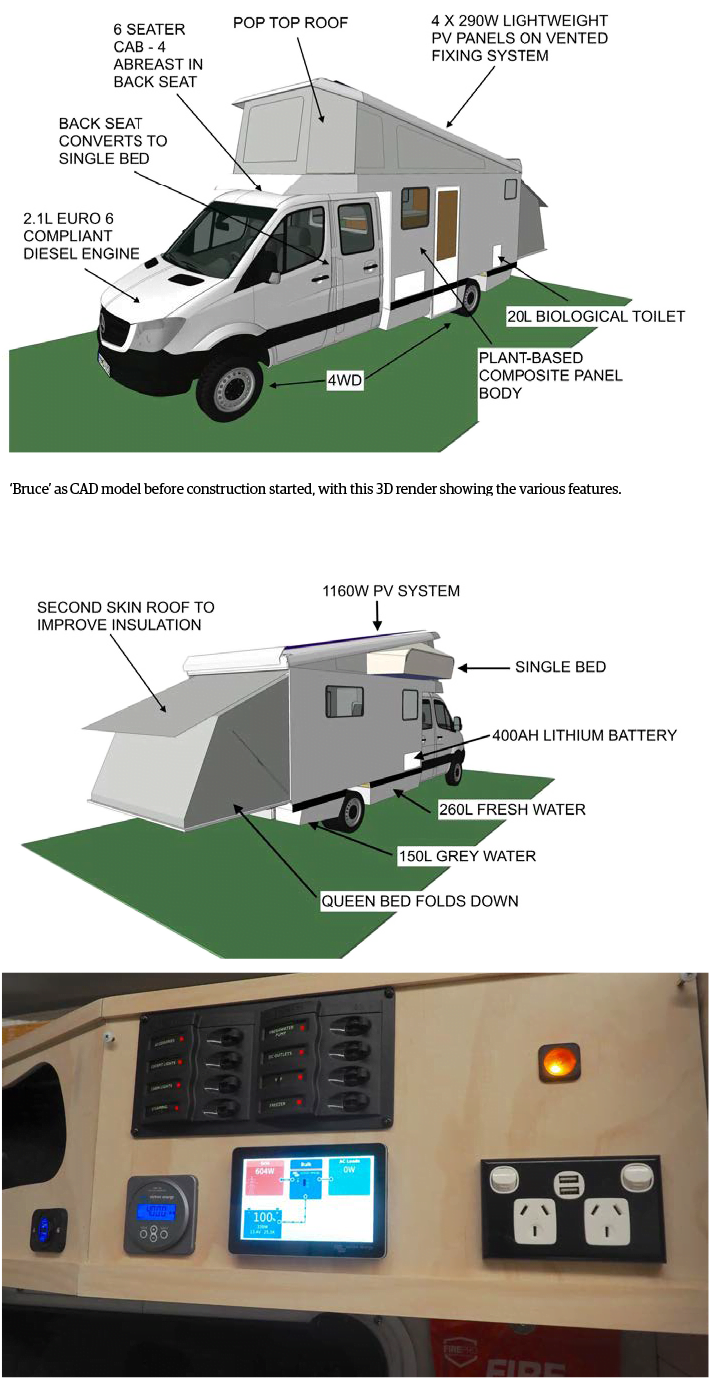

The design is a rear hinged pop-top, with a double bed over the cab, and queen bed that drops down at the rear like a cross between a horse float and a camper trailer, a single bed on the back seat of the cab, and another single on the settee. A single side cantilevered bed has been designed but not yet installed. The roof pops up on gas struts, and the rear bed raises and lowers on a clutch winch.

Plant-based composite panels

The structure I settled on is a composite panel, like my previous van and my boat, but with renewable materials: end-grain balsa core (where the timber is cut into short lengths and laid up with the end grain exposed), with flax fabric reinforcing in place of the usual fibreglass fabric, all glued together with a bio-epoxy resin derived from canola oil. I cannot tell you how in love I am with the bio-epoxy, and my neighbours too—compared to the nasty styrene that off-gasses during the curing of polyester resins, this is odour free.

The panels were laid up to my design by the good people at ATL Composites on the Gold Coast, and sent down to Sydney by truck—another bit of carbon to be accounted for. They come as a beautiful dark brown tweed pattern, and Sanctuary readers may recall Ian Wright’s house in Brisbane built using the same system (see Sanctuary 50). These are so strong that no additional sub-structure is needed under the floor—it is simply bolted directly to the chassis mounting brackets and to the back of the cab. Because European trucks are designed without chassis twist, the connection is very simple.

Panels are joined with bio-epoxy and carbon fibre cloth—another non-renewable compromise, only because flax of sufficient strength is not available in tape form. Once joined, the filling and fairing uses powder from previous sanding jobs mixed with the bio-epoxy, an orbital sander, and elbow grease. The external finish is a conventional automotive paint, as no plant-based paint I could find is hard enough or glossy enough to withstand constant UV exposure, heat and cold, stone flicks, and scrapes from branches. One day, maybe.

Lightweight timber interior and gas-free!

Bruce’s interior joinery is all made from plantation grown hoop pine timber and radiata pine ply. The sections used are slender, with high joint strength achieved by being glued and screwed together. Drawer bodies are 3 mm ply with strong timber corners, and the drawer fronts are made from 12 mm radiata ply. The ‘Nordic Noir’ colour scheme was dictated by my collective daughters-in-law, with some quirky features and secret hidey-holes to keep life interesting for the kids. In reality, this is to ensure that there is no wasted space—empty volume is the enemy in my design ethos. Even the central corridor is used to carry surfboards and extra bags when needed.

The other major goal, as with everything we design these days, is to be gas-free. Thanks to Renew’s “Getting off gas” series, and the general push from design industry leaders, this is becoming mainstream in buildings, but is still decidedly unusual in the RV industry. In fact, the industry as a whole is still way off the pace in sustainability, something I try to make waves to fix.

The interior and sleeping arrangements have always had the tropics in mind. In cold climates you can always add another layer, but in 30°C-plus nights with 80% humidity, and choosing not to rely on mains power or generators for air conditioning, the interior has to use passive cooling techniques. Shading and tinted windows keep sun out in hot conditions, and cross ventilation is provided by massive windows, assisted by two fans. It works very well, albeit with a bit of acclimatisation. At Cobold Gorge we had 40°C days with 35°C nights, and a water spray bottle helped us drift off to sleep, with a slightly damp sheet and the fan going flat stick.

The PV system uses four 290 W lightweight solar panels, running through a pair of solar controllers to a pair of 200 Ah lithium batteries (400 Ah, 12 V in total). The control system and 230 V inverter is Victron, and even in 40°C heat with fridge compressors running most of the day we had plenty of power. Lighting is all LED, the 208 L fridge/freezer is an Evakool 12 V unit, and the 12 V, 10 L electric hot water system is a Duoetto Mk2. Flooring is a 100% recycled rubber and cork zero-VOC composite made in Melbourne by ComCork.

The Thetford toilet is a common RV chemical toilet, but we use wonderful bio-active granules called Flush-It, supplied by Biomaster, which eliminate that awful chemical smell, last for a week or more in 35°C heat, and are completely benign in septic systems.

Voyages

Bruce has had a few voyages since lockdown ended, the biggest being when we recently drove it to Cairns with grandkids in tow. Two adults and two kids in a six-berth van sounds like luxury—and it was!—but it’s curious how quickly people and things expand to fill all available space! Especially when kids amass the inevitable collections of treasures.

What was supposed to be a five-week trip ended up being nearer three months, thanks to the coal miners’ ineffective maintenance (front lower ball joint and a wheel bearing failures, handbrake pads never having been serviced and going metal to metal, flywheel parting company with the clutch), FNQ’s chronic shortage of trades and professionals (four-week wait for mechanics, medical district being short 300 medicos etc), and Mercedes’ parts network supplying the wrong parts three times in a row, with a week or more’s wait to correct each time.

On the upside, we got to know Cairns and the wonderful blokes at the Cairns Mechanical Workshop very well. It is a lovely city with coffee to rival Melbourne (shock, horror), and well set up for cycling—thankfully we had our bikes with us too, so rode almost everywhere. I set up a temporary office on a friend’s veranda, and later in Bruce. The travellers’ grapevine soon spreads the word on the best places to hotspot.

On our way up through the middle of Queensland we communed with platypus in Carnarvon Gorge, avoided confrontations with angry coal miners in Clermont, were blown away by the awesomeness of Undara Lava Tubes, and fell in love with the red hot flood-polished walls of Cobold Gorge. At the Willows State School in Townsville we crossed paths with the ‘Charge Around Australia’ Tesla EV making its way around the country on solar power using newly developed printed PV technology from the University of Newcastle (see Renew 161).

We cried with our granddaughter at the worsening condition of some of the coral at Green Island, laughed with our grandson doing backflips with the locals and tourists alike in the lagoon on Cairns’ waterfront, and thought we were hallucinating looking at the brilliant greens of the Atherton Tablelands—so green it almost hurts!

By the time we left Cairns, the stinger nets were up on the beaches, and we had to get out of the water to cool off. Townsville has a beautiful translucent sculpture sitting in the ocean just off the esplanade, which glows with different colours according to water temperature on the outer reef, going from blue through green and yellow to red as the temperature increases.

When we first saw it in September the sculpture was blue-green. When we left in November it was definitely shifting from orange to red. The first full moon in November is coral-spawning night, and while we were tucked up in bed in a roadside stop on the Bruce Highway (always looking for the bush camps and freebies!) they were having their annual orgy just a few kilometres away. Go for it coral, make lots and lots of babies!

We finally headed south some weeks later than planned, meeting up with old friends en route, and enjoying the cooler weather and water further south. Right up until an overtaking Kenworth decided to give us a fat nudge forward as it went past, hitting our rear corner. It was certainly a shock, but could have been a whole lot worse—we stopped the sleeping driver from drifting right off the motorway to a premature grave. The stiffness of the composite construction was evidenced in the relatively minor damage, and having the semi’s kinetic energy adding to Bruce’s kinetic energy in a nano-second, like being shot out of a catapult. Damage? Never mind, it’s only money. And maybe a life saved.

Bruce the better motorhome—vitals

- Base vehicle—2012 Mercedes Sprinter 516CDI dual cab 4×4, 2.1 litre diesel Euro6 compliant

- Motorhome body unitary composite construction a la ‘Wild Oats X1’ maxi yachts, supplied by ATL Composites in Queensland.

- Composite is plant based:

•End-grain balsa core 20 mm thick roof, 25 mm thick walls, 50 mm thick floor

•Flax fabric reinforcing skins both sides

•Bio-epoxy resin derived from canola oil - Body is bolted direct to chassis, no subframe needed (also keeps floor low so more headroom)

- Interior joinery is framed in clear hoop pine (SE Qld plantation grown), drawers and door fronts radiata pine ply (NSW plantation grown), glued and screwed together

•Finished in white liming and clear water based zero-VOC lacquer

•Walls lined with Autex ‘Composition’ recycled PET panels - Cushions and covers Hemp Gallery ‘Newport’ hard wearing hemp fabric

- Flooring ComCork recycled rubber and cork composite sheet

- Electrical system:

•1160 W PV system—4 x 290 W lightweight panels

•Victron solar controllers and programmable BMS

•Daly-SMART LiFePO4 battery 400 Ah

•1600 W, 230 V Victron inverter

•Duoetto 12 V hot water system (no gas)

•Origo 4000 two-burner metho stove (no gas)

•Evakool 208 litre fridge and freezer 12 V (no gas)

•12 V water pressure pump

•12 V fans x 2

•LED lights internal and yellow external (no bugs) - Pop-top roof lifts on custom gas struts from Gas Struts Australia in Brisbane, rear bed lowers and raises using a Jarret clutch winch made in Adelaide

- All canvas is breathable Sunbrella poly for UV and mould resistance—but not grown in a paddock

- 260 litres fresh water and 150 litres grey water storage in 316 stainless tanks by Hannan Stainless

- Built during 2020-21 lockdown in my spare time.

Further reading

Transport & travel

Transport & travel

Petroleum is fast becoming a dirty word

John Hermans explains the negatives of the petroleum industry.

Read more DIY

DIY

Bring on the electric ute

Bryce Gaton asks, will 2023 be the Australian ‘Year of the electric light commercial vehicle’?

Read more Transport & travel

Transport & travel

Biofuel vs battery

John Hermans gives his opinion on the best power source for electric vehicles.

Read more