Petroleum is fast becoming a dirty word

John Hermans explains why.

It is undeniably the stored energy source that has enabled the past few human generations to become so affluent, to the point that we now critically depend on it.

From the outset, I claim that ‘petroleum is a poison’—perhaps a controversial stance. Its toxic credentials are evident in both its liquid pre-combusted state as well as its burnt gaseous state.

If you were to ingest just a few millilitres of either petrol, diesel or avgas, and swill its content around in your mouth, it may not kill you, but its toxic impact will scar your health and your memory of the event. Any contact with the lungs, skin or gut is toxic.

Toxicity aside, the list of negative implications from the petroleum industry is enormous.

Take crude oil for a start. Unprocessed crude oil has had a massive impact on the world’s ecosystems. Oil spills have led to horrendous out-of-control disasters, where sea animals in particular have been killed in their millions.

With 5,800 million tonnes of crude oil mined annually, its capacity to inadvertently contaminate our living spaces is vastly underestimated. The fracking of underground gas reserves impacts freshwater ecosystems. Leakage from storage vessels in vehicle refuelling stations is an international problem that goes on in perpetuity.

The practice of applying lead to petrol to improve its combustion performance left a disgraceful human health legacy for almost a century.

Once petrochemicals are combusted, the emitted tailpipe exhaust represents a plethora of toxic gasses. These airborne particulates do their greatest damage to health, reducing lifespans in cities across the globe, and contributing to a far greater percentage of human deaths than all other causes combined (see Table 1 – note, cardiovascular disease and cancer are leading killers, but it is unknown what percentage of these are due to fossil fuels).

| Table 1. Human deaths per annum. | |

|---|---|

| Wars | 50,000 |

| Murders | 470,000 |

| Road accidents | 1.3 million |

| Obesity | 2.8 million |

| Air pollution from fossil fuels | 8.7 million |

My own family recently understood that petroleum products are an unacceptable form of energy to be using. Acceptance remains the default position for most people. Feeling okay about relying on a product that has such vast negative impacts on so many aspects of all life can only persist whilst the users are complicit in believing that they have ‘no other choice’.

Well, I am here to tell you that is no longer the case!

Four years ago, our low-income family purchased a fully battery-electric Nissan Leaf, a used import from Japan. Being committed early adopters, we managed to recharge our 100km-range Leaf on 100% renewable solar power from our off-grid home power system.

With many short-distance trips, the well-utilised EV clocked up over 40,000km in four years, marking the start of our departure from liquid fossil fuels.

Petroleum, as a form of stored energy, is derived from the decay of a multitude of prehistoric animals and plants. These ancient life forms captured their energy from the same sun that we take our current solar energy from—we just take it and use it directly.

This modern-day option is made simpler with the use of newly developed lithium ion batteries, and for our household, a large assortment of second-life PV panels. In 2023, we upgraded to a longer-range Hyundai Kona BEV, still powered by 100% solar energy input. Its 450km range gives freedom and flexibility similar to ICE vehicles we previously owned. For many years, our family vehicle fleet was powered by waste vegetable oil and biodiesel (see story in Renew 164).

In Australia, we import more than 90% of the petroleum we consume. National fuel reserves of petrol and diesel will go little more than three weeks before all supplies are exhausted, without continued foreign import. This predicament leaves Australia as a price taker of world crude, with high market vulnerability.

Yet demand-side solutions, particularly the electrification of transportation, have been ignored. Due to the lack of a fuel emissions standard, this country’s per capita CO2 emissions were the highest on the planet in 2019, and vehicle tailpipe gases are the primary reason (Our World in Data).

Our previous federal government’s non-agreement on vehicle emissions standards has limited our EV import options. To compound this appalling situation, the former prime minister Scott Morrison made clear his intentions to discourage the rollout of EVs across Australia.

Clearly, by suppressing renewable industries and continued subsidies to oil refineries of almost $2 billion, he ranks as Australia’s leading climate criminal. Wilful climate denialism in our political leaders is abhorrent.

The CO2 emissions associated with the burning of liquid fuels represents about 2.5kg per litre of combusted petrol as you travel. However, on top of that, energy used in refining that fuel adds another kilogram of CO2 in what is known as the ‘well to wheel’ total of CO2 emissions. By avoiding burning each litre of fuel, we avoid emitting 3.5kg of CO2, and free up a significant amount of electricity to be available for EV charging.

With lithium-based batteries to assist the storage of renewable energy, EV users have the opportunity to use clean, low-cost renewable power to significantly reduce their CO2 travel emissions.

In our personal EV ownership experience, which sees us living off-grid, our e-fuel costs were zero. Our current vehicle energy and its availability is now exceptionally secure.

It is notable that around two-thirds of EV owners have a home solar PV system to maximise their renewable transport energy.

The current anti-EV mantra being fed to the wealthy world of new car owners predominantly argues that new replacement EVs would put excessive demands on limited volumes of critical minerals such as lithium and its energy use from processing.

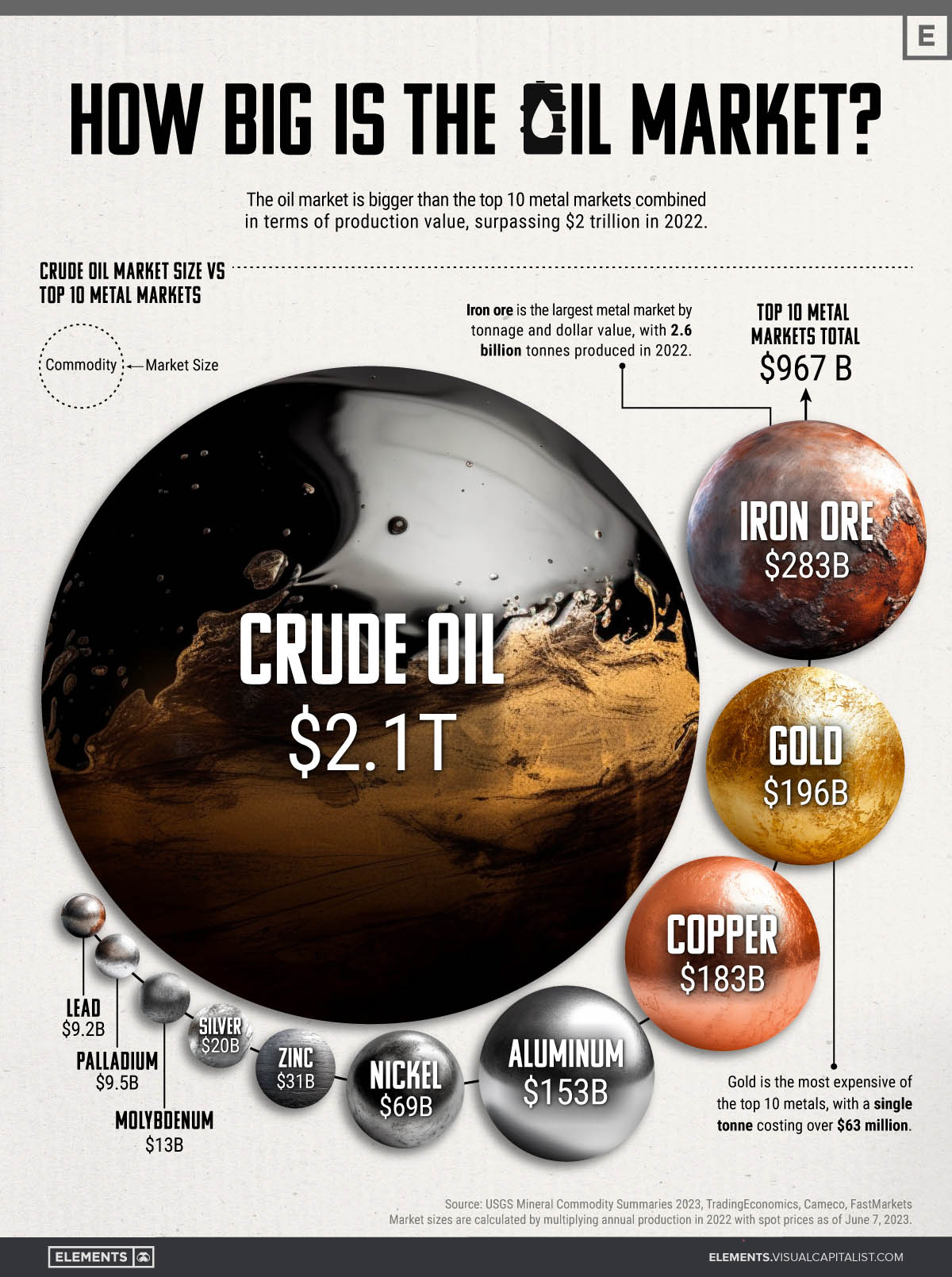

Looking at the ‘crude oil’ infographic put together by Visual Capitalist, you will note the huge annual dollar value of global crude oil—at over US$2 trillion, which equates to the 5,800 million tonnes of crude oil mined annually. This is twice the financial turnover of all other mined minerals combined.

The market value of copper on the infographic gives some idea of the volumes of an essential metal at the start of our renewable energy economy—22 million tonnes per annum. Lithium’s annual production value is still a tiny fraction (170 times less, not even on the chart).

To reduce this petroleum dependence, the annual mined volume of lithium needs to increase massively from its comparatively current small amount of 130,000 tonnes per annum.

Recent developments in lithium mining processes for the expansive Australian hard rock deposits have significantly reduced its ‘specific energy of production rate’. This is via the use of a patented LieNa process.

Also, fast brine processing is using newer Direct Lithium Extraction (DLE) methods, instead of the traditional water consumptive evaporation ponds. This DLE process will be used alongside the Salton Sea in Southern California, where there are already 11 geothermal renewable energy power plants drawing up boiling hot water to provide electricity for that area. The extracted water is rich in lithium salts, and is currently pumped back into the aquifer that it was drawn up from for reheating.

By passing this lithium-containing fluid through the DLE process before reinjection, it is predicted that there will be enough lithium resource for all the needs of the US, plus export capacity.

This mineral extraction process consumes minimal water, digs no mine pits, generates renewable energy, and is calling for the ecological rehabilitation of the Salton Sea.

Ethical and environmental scrutiny of every essential mining procedure is essential.

Another factor progressively reducing the need for lithium in vehicle manufacturing has been the increased energy density of new batteries. The 2014 Nissan Leaf our family used for four years has a 24kWh battery that weighed 300kg. Our next family EV, the 2019 Hyundai Kona, had a battery of similar weight but an energy content of 64kWh, almost tripling the range with a similar amount of lithium.

In 2022, 30% of EVs were fitted with lithium iron phosphate batteries. With an annual growth rate of 20%, these batteries contain no cobalt, nickel or manganese.

This year there have been several independent lithium battery manufacturers beginning the production of batteries in excess of 400Wh/kg (nearly double the current standard).

Included in this mix are the development of sodium batteries and the dual carbon battery, containing no metal cathode. By the time our Hyundai Kona battery is due for recycling, the batteries of that day will be considerably more energy dense, making them even more sustainable and highly cost effective.

When lithium batteries end their useful life, the valuable chemical elements within ensure they will be recycled. Ninety-eight percent of all lead acid batteries, despite their current low value of 35 cents/kg, are recycled. In this way, the need to continue an exponential rate of extraction is avoided.

Very soon, internal combustion engines will make no economic sense. The toxicity of petroleum and its deepening curse on global warming drive this point home. Many EVs are now comparable in price to petrol and diesel cars, are cheaper to run, eliminate petrol and diesel altogether, and if powered by renewable electricity, have a significant impact on reducing carbon dioxide pollution.

Opponents of EVs imply that petroleum use will never come to an end. Do those naysayers have an option for our future? These arguments have no place in a world on the brink of a climate catastrophe.

People from high CO2 emitting countries (like Australia and the USA) should be using their relative wealth and product choices to promote a reduction in per capita petroleum use, in a similar way that we have been Getting off Gas.

The time to “stop burning stuff” has begun, which means seriously thinking about how you can Get off Petroleum. Because now, you have a choice.

Further reading

DIY

DIY

Bring on the electric ute

Bryce Gaton asks, will 2023 be the Australian ‘Year of the electric light commercial vehicle’?

Read more Transport & travel

Transport & travel

Biofuel vs battery

John Hermans gives his opinion on the best power source for electric vehicles.

Read more DIY

DIY

Aussie women: the solar power pioneers

Sun Source was Australia’s first solar panel retailer, started by a hippy woman nearly 50 years ago. Kassia Klinger uncovers the story.

Read more