What is ethical investing?

Ethical investing is booming. But there are important questions potential investors should ask before jumping aboard, explains Sophie Weiner.

In recent years, more and more of us have become interested in knowing how our invested money is being spent and making sure it’s being used for good. As a result, terms like impact investing and ethical investing can now be found in any mainstream financial journal or newspaper. With growing awareness of the dire consequences of unchecked climate change, people are more determined to make their investments spark positive action rather than maintaining the status quo.

But ethical investment is far from simple. For those who have money to invest, there are nearly endless options available. Many ‘green’ financial products aren’t as sustainable as they advertise themselves to be. In other areas, such as superannuation, many consumers feel they don’t have the level of choice or transparency they’d like. Even figuring out what to do with the investments you already have can be a challenge—some advise divestment from anything fossil fuel related, while others say keeping a stake in problematic companies can allow shareholders to encourage them to do better.

Here, we lay out some of the basics of ethical investing and provide a framework to understand both its opportunities and pitfalls.

What is ethical investing?

Environmental concerns are a fairly new component of what’s known as ethical investing. Historically, ethical investments or products were those that excluded ’sin’ companies, like gambling companies or those that sell alcohol, cigarettes and firearms. Some came to see these investments as a stain on their portfolios for reasons that ranged from moral to religious. But over the past several decades, sustainable investment has taken centre stage for many ethical investors. These investments are often labelled environmental, social and governance (ESG) investments.

The market for sustainable investments is growing rapidly. In 2017, US $30.7 trillion was held in investments labeled sustainable or green, an increase of 34% from 2016, according to a report from the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance on five major world regions (bit.ly/39mz7ik). Incredibly, this amounts to nearly a third of all investments managed by financial management firms (except for those that can’t be tracked for whatever reason), and in some places closer to half, according to Bloomberg (bloom.bg/2xe81eR).

These green investments run the gamut of financial products, from funds, which use money from many individuals to invest jointly, to bonds, which are a form of debt issued by companies or governments in which both individuals or funds may invest. Mutual funds allow investors exposure to many different types of investment opportunities at once, while bonds usually fund a specific company. Green bonds have been particularly successful in recent years as companies find them an effective tool to raise capital for any project that can be marketed as sustainable.

Even our parent organisation Renew has used funds from impact investing to help install a 36 kW solar system on an Indigenous community centre in WA (see image further down).

Institutions themselves are shifting thanks to this mandate from consumers. A new global ethical banking movement is trying to win customers by promising to be transparent and environmentally conscious.

This should be exciting news for anyone who believes in green infrastructure replacing fossil fuels. There is clearly enough capital out there to finance the shift to a lower carbon world.

But though the energy around green finance is exciting, it’s not always clear that these bonds and funds are as green as they say. There are many different rating systems for green bonds and little regulation around what can be called sustainable. Some companies selling green bonds have been accused of greenwashing, marketing their products as green when they do little or nothing to promote sustainability. Entities like the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) are attempting to change this by bringing more transparencey to the booming new industry.

Hiring a financial advisor is essential for potential investors who want to navigate the profusion of green investment opportunities. Financial advisors who specialise in green investing ask clients in detail about their priorities and research which products fulfil their criteria. This can help people get the investments they want and understand difficult decisions.

“Each client is different and might have a different perspective on ethical investing,” says Mary Campbell, a financial advisor and ethical investing specialist at Gold Leaf Financial Services.

As with any professional you trust with important decisions, it’s important to research financial advisors and check their credentials before making a decision.

Financial advisors are also valuable due to the complexity of investing in emerging industries, where there isn’t always a public company to buy shares in.

“One of the challenges with investing in renewables is that they tend to not be publicly listed companies,” says Tom Swann, a senior researcher at the Australia Institute.

Tom says that in the past, financial managers have had to find workarounds to get clients invested in renewable technologies. But it is getting easier as bigger, publicly listed companies invest in renewable infrastructure.

“There are increasingly shares you can buy,” he says.

Dr. John Halstead, a policy and charity researcher, says that investing in “large public stock markets” may be the least impactful way to invest, because it’s unlikely to actually affect the amount of capital available to a company. He recommends looking into venture capital or angel investing instead.

“For encouraging technologies, I would think that supporting non-profits that advocate at the national level would be the best way forward,” John told Renew.

“Few impact investors think about impact in a rigorous or systematic way,” he adds. “Many of them miss the question: ‘did I affect the company compared to what would otherwise have happened?’”

How do ethical investments perform?

There’s a lot of debate around the performance of ethical investment funds and bonds. Many studies find that the funds perform as well or in some cases even better than regular funds, while other studies show them performing slightly worse. It can be hard to weed through these studies, some of which are funded by industries with an interest in their results. Some academics believe the industry and its effectiveness is under-researched.

And investing in a future dominated by fossil fuels presents its own financial risks, even if it promises short-term rewards. As industry inevitably shifts away from fossil fuels, those who are financially tied to them are likely to lose out.

Tom emphasises the great financial risks presented by climate change for those who don’t diversify and divest from fossil fuels. The market may change quickly if prominent nations decide to change their policies to limit climate degradation. Natural disasters like fires or hurricanes, events that will become increasingly common as climate change progresses, can also contribute to unpredictable market fluctuations.

“The key question is whether the next 70 years for oil is going to be the same as the last 70 years,” Tom says. “Everyone thinks they can sell their shares before the risks materialise, but not everyone can do that.”

What about divestment?

As an ethical investor, deciding which industries or companies to avoid can be as important as figuring out which to support. Divestment has been a major focus of those fighting to make the finance sector more sustainable and has had major impacts on the financial industry. In practice, divestment involves an institution or individual selling their shares in a company with which they no longer want to be associated. That means that someone else is willing to buy those shares. Thus, it’s not clear if divestment campaigns impact the company’s value via their share prices. But that doesn’t mean they’re ineffective. The negative media attention that divestment campaigns generate has serious consequences for companies, and even whole industries. Thanks to high-profile campaigns, it’s becoming more difficult for companies involved in harmful projects to get money to finance projects, like the Adani mine, or even to recruit new employees.

“Critics of divestment often say it’s symbolic, and they’re right,” says Tom. “But symbols are incredibly powerful. That’s why the fossil fuel industry has been so concerned about divestment and put so much money into fighting divestment.”

Tom was involved in the campaign to convince Australian National University to divest from fossil fuels in 2014, which led to the university’s partial divestment from coal. He pointed out that the campaign drew the ire of former Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s government, which spent weeks fuming about the decision, attracting a huge amount of attention to the cause.

Shareholder strategies

Some activists advocate a different strategy. Rather than completely divesting from harmful companies, they believe that continuing to hold stock can allow engagement with the companies through shareholder advocacy. Corporations are, theoretically at least, meant to function as democracies run by shareholders. If enough shareholders are unhappy with a company’s conduct, they can push for change.

The Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility is one organisation that uses this model in their work. The ACCR engages with companies whose behaviour they disagree with, asking them on behalf of shareholders to change. If that doesn’t work, ACCR will bring a shareholder resolution to a company’s annual general meeting, a way to publicly air the company’s dirty laundry. Resolutions need a very high percentage of support to be adopted by a company, but the public pressure and bad press alone can be enough to force a company to take action. As part of their campaign against coal industry lobbying, ACCR was successful in getting mining company BDH, which claims to support sustainability, to leave the World Coal Association and re-examine its relationship with the Minerals Council of Australia. Another recent resolution calls for Australian energy company Santos and Woodside Petroleum to suspend their memberships of the Australian Petroleum Production and Exploration Association and the Business Council of Australia and to set emissions reduction targets aligned with the Paris Agreement.

“We exist in very complicated systems, so it makes sense to act on those systems at all levels,” Emma Batchelor, who works in shareholder recruitment at ACCR, says of the tactic. “If we want to break down and rewrite and change the system, we need to attack it from all different angles.”

Ethical super

Thanks to superannuation, all Australians are technically ‘investors’ with a stake in the market. That gives us a unique position to make decisions about ethical investment. Super funds are becoming increasingly powerful. A report from the Australian Financial Review in 2019 (bit.ly/2VHfNIx) found that super funds will own two-thirds of the shares in the Australian market in the next 20 years. If this prediction holds true, super funds will have the power to appoint board members at many Australian companies and steer their decisions.

But if we don’t know what’s in our super funds, we can’t harness that power. Historically, it’s been hard for most people to find out which shares were in their super funds. In 2012, public holdings disclosure provisions were introduced that would force super funds to disclose their investments. Those provisions are supposed to finally come into effect at the end of 2020.

As the idea of ethical super funds has spread, some super funds, like Australian Ethical, have chosen to voluntarily disclose their investments, along with detailed justification for why they believe their choices are ethical. Australian Ethical uses a 24-point ethical charter to make decisions about what to invest in. These fall along lines of encouraging clean energy, discouraging abuse of workers and animals and limiting climate change.

These decisions can often be complex. For example, many large banks invest in both renewable projects and fossil fuels. Australian Ethical says they use a climate scorecard to rate banks’ sustainable credentials. The scorecard includes the bank’s lending to fossil fuel projects, including the type of fuel, its lending to renewables projects and lending to “technologies and activities which reduce energy usage or store carbon (e.g, green buildings, low-emissions transport and reforestation).”

Despite the trend towards ethical super funds, until the new regulation goes into effect, many will remain a black box. The activist organisation Market Forces has done extensive research on which super funds are in line with environmentalist concerns, which can help consumers who want to switch to a super that aligns more closely with their values (see their report at bit.ly/3a7kyPR).

With resources like those from Market Forces, Australians can learn more about their super and what it invests in. Pressure from the public may force these businesses to divest from certain industries or change their portfolios. As super funds hold large numbers of shares, they have a bigger voice as investors than any individual, and their decision to pull out of an industry or company can be impactful.

“The vast majority of Australians and people around the world expect climate action to be taken,” says Will van de Pol of Market Forces. “It’s up to us to pressure the institutions that have custody of our money to take the actions we know are necessary to meet the challenge of climate change.”

Green investing tips from a financial advisor

- Learn about money and investing, including understanding risk and asset classes, from the Australian government Moneysmart website at moneysmart.gov.au.

- You can use the Responsible Investment Association Australasia’s Responsible Returns website (responsiblereturns.com.au) to search for certified ethical investment products that take into account particular environmental issues.

- Look at the holdings of a super fund or investment fund. This will give you an idea of how they apply their ethical investment process in practice.

- Look for thresholds on issues, e.g. some funds will allow investment in fossil fuels as long as it is less than 20% of the company’s revenue in that activity.

- Read the ethical investment policy and disclosure documents to understand how screening is applied. Does the fund just exclude brown coal, or does it exclude all coal, oil and gas?

- Consider the supply chain. Does the company just exclude production (e.g. oil extraction), or does this extend to distribution (e.g. petrol stations, gas pipelines).

- How broad is the exclusion; e.g. does it extend to services provided to that activity? What about services to fossil fuel companies such as from IT or engineering companies, or banks providing finance?

- What are the positive screening methods? Is there exposure to renewable energy, energy efficiency, water efficiency or recycling? What percentage of the investments are having a positive impact on the environment?

- Engage with companies. Use your voice as a super fund member, investor or shareholder to write to companies and ask for better environmental standards for your investments. The Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (accr.org.au) is an NGO in this area.

Adapted from suggestions by Mary Campbell, financial advisor and ethical investing specialist at Gold Leaf Financial Services goldleaffinancial.com.au

Resources:

Market Forces: marketforces.org.au

Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility: accr.org.au

Financial advisors registry: bit.ly/2Web1m8

Responsible Investment Association Australasia: responsibleinvestment.org

Further reading

Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Community energy sharing challenges and solutions

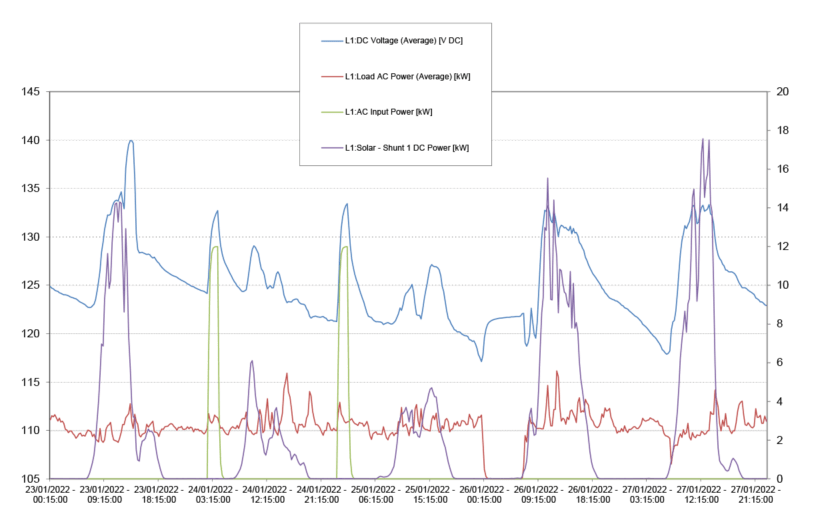

Oliver Crowder from Saltwater Solar reports on a remote community solar system he helped set up more than 10 years ago.

Read more Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Breaking the barriers to innovation

Rob McCann looks at the big sustainability innovations of the past, and implores us not to become a nation of laggards.

Read more Sustainable tech

Sustainable tech

Lithium battery fires and safety

Rechargeable lithium batteries are critical for our modern world, but they do have a somewhat variable safety history. Lance Turner looks at the issues and what to do about them.

Read more