From little things…

Many white Australians were taught at school that the Aboriginal cultures displaced and destroyed by European invasion had no concept of agriculture. The growing awareness of the falsity of this claim has driven an increased interest in edible plants native to Australia. But this has raised issues of its own, including the question of who benefits from the commercialisation of traditional Aboriginal foods. Larissa Dubrowsky-Ryan reports.

Ultimately, says Arabella Douglas, core Indigenous values are about “eco before ego”.

Douglas is a proud Minyunbal woman, and founder of Currie Country—named after James and Ellen Currie, traditional land owners in a region near the border of Queensland and New South Wales, and Douglas’ great-great-grandparents. Currie Country operates like a cousin consortium, encapsulating many small Indigenous owned businesses and foundations that share ancestral ties.

Douglas started the project 14 years ago after seeing gaps in cultural knowledge across different groups. One of Currie Country’s largest missions, as she explains, is to make sure Indigenous people feel “culturally confident in their own systems”, along with providing a space for others to learn about Indigenous practices.

Currie Country explores connection to spirit, country, community and environment, including native foods. But as Douglas points out, it’s about more than just tasting new flavours. “People see [Indigenous food] on a plate and think, ‘That’s great,’”, she says, “but the foundation is dedicated to sustaining [First Nations peoples’] own cultural education.”

The myth that Aboriginal Australians were merely hunter-gatherers who relied on nomadic movement to sustain themselves was and remains a damaging—and false—assumption. The lack of what Europeans perceived as agriculture—dense, intensive farms feeding closely-gathered populations—was one of the most significant justifications for the terra nullius myth used to justify the white invasion of Australia. This same lack of understanding of Indigenous cultivation and agricultural methods continues to drive environmental destruction and over-farming.

Far from being hunter-gatherers, Aboriginal Australians managed “the biggest estate on earth”, to quote historian Bill Gammage—and did so successfully for over 65,000 years. Before British invaders arrived, these cultures employed complex and sophisticated methods of land care, allowing them to enjoy anywhere between 150 to 750 different kinds of food a year, depending on seasonality and location. By contrast, even today, for the average European Australian, this number is under 100.

From using fire to distribute plant seeds and observing the movement of stars to guide seasonal planting to building dams and wells, Indigenous people were the first farmers this land saw. Over many generations, they evolved a culture that worked in co-cooperation with the land, rather than seeing it as a thing to be bent to their will.

When the British invaded Australia, these traditional practices were lost or suppressed—and once the settlers were entrenched, they became impossible to continue. As Bruce Pascoe writes in Dark Emu, “You [can’t] do broad acre agricultural activities once the land had been taken from you”. As well as the material implications of land theft, Pascoe’s quote alludes to the cultural impact of the invasion—something echoed by Douglas, who explains how the impact of colonialism goes well beyond disenfranchisement: “The colonial impact is to cast doubt on your ability, your trust, your beauty, your function, your sexuality.”

Colonialism’s impact on the land was similarly profound, and similarly destructive: in barely a generation or two, European agricultural systems for land management replaced traditional practices, and are still the dominant methods used today.

Image: Supplied

Australia is a difficult land to farm. The relative paucity of nutrients in much of its soil—in comparison to the soil in Europe, at least—means that the land’s ability to support crops can be exhausted quickly. Early European settlers discovered this to their cost. In his book The Future Eaters, Tim Flannery describes a recurrent pattern where settlers would plant crops, enjoy a bounty when those crops were reaped, re-plant them the following spring—and starve. The thin soil simply couldn’t support the nutrient-hungry grains that settlers planted, and the inevitable failed crops in the second year of settlement spelled famine, hardship, and eventually disaster.

Year by year, though, the settlers found ways to survive here—mostly by forcing the land into submission. They cleared the native grasses and shrubs that provided vital protection to the land, resulting in the erosion and degradation that we still witness today. They brought livestock and, eventually, nitrogen-laden fertilisers. The result—along with the almost complete extermination of an Indigenous population that had cared for the land for uncountable generations—has been a dramatic swing toward agricultural practices that are unsuitable for the land onto which they have been imposed. These practices are therefore also fundamentally unsustainable.

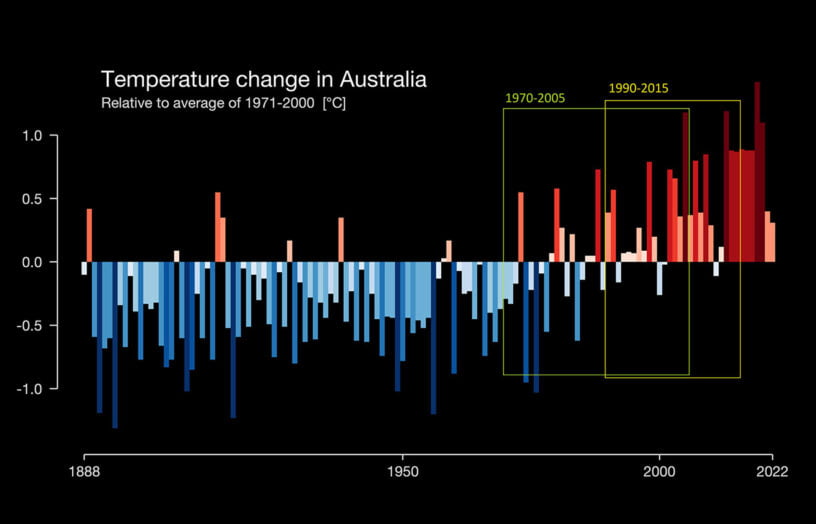

The growing awareness of this fact, along with a rising interest in sustainable living in the face of climate change—and, most importantly, a slow recognition that listening to Indigenous voices might actually be a good idea—has meant the benefits of both Indigenous foods, and the traditional methods of cultivating and reaping those foods, are being recognised at last.

So what are those benefits? One of the most important differences between European and native plants is their relative water consumption. Many Australian plants are adapted to dry periods, low water availability and the other environmental stresses that characterise this continent—and as a result, they consume far less water than their European counterparts. Shifting to plants that are already suited to Australian conditions could drastically reduce water consumption: around 60% of Australia’s water is currently used for irrigated agriculture. (And 30% of our household water is hosed onto our gardens.)

As the planet heats up and water becomes ever more scarce, the cost of the intensive farming that supports European crops and livestock can no longer be ignored. This cost—and the accompanying damage to Australia’s unique ecosystems—could be mitigated by the commercial growth of native Australian foods. Such a change would also mean that our country could begin to move toward a food system that could support and help preserve native ecosystems, rather than being the cause of their devastation.

Aside from these environmental benefits, native food sources also come brimming with health and nutritional benefits. For example, the Kakadu plum, or gubinge, contains over 100 times the vitamin C of the humble orange, and five times the antioxidants found in blueberries. The bark is also traditionally used for skin health and treating wounds. Wattles are often admired for their bright flowers, which provide a comforting reminder that summer is on the way, but their seeds have even more to offer. When the pods are harvested, the seeds inside can be dried and ground into a flour full of protein, magnesium, calcium, zinc, and iron. The list of nutritional benefits and vitamins that native plants hold goes on and on.

There are an estimated 6400 native foods and botanicals known, but only 18 are currently in commercial production. This is largely due to the food safety process, which involves research into native plants’ toxicity and composition, and also working out how to adapt commercial processing methods to suit these plants. But as Chris Andrews, the manager of Indigenous-owned social enterprise Black Duck Foods, argues, “Nothing tells you a food is safer [better] than having 65,000 years of history behind it.”

For Arabella Douglas, looking towards Aboriginal food systems is a holistic remedy to global warming and the over-farming of Australia’s land. it’s less about the individual food items than the whole structure—from logistical know-how to a spiritual awareness of celestial movements. Together, the complex practice replenishes and regenerates the land.

Illustration: Iryna Zaichenko/iStockPhoto

As the native food industry grows, many have voiced concerns over how it impacts Indigenous communities and the part they play in the growing boom. With Indigenous Australian foods being placed under the same “superfood” label as the likes of quinoa and cacao, the industry is only going to expand. However, global lessons demonstrate this global embrace is not always positive for the local communities who produce these suddenly hot commodities.

Quinoa, for example, has been a staple grain for the Incas and Andean people of Peru and Bolivia for thousands of years. Before the turn of the millennium, few outside those countries had even heard of it. However, its sudden explosion in popularity in the 2000s—driven by superfood hype—meant prices tripled between 2006 and 2013, and it is now the world’s most expensive grain.

It was widely reported in the mid 2010s that the skyrocketing price meant that many of the indigenous communities that had grown quinoa for centuries could suddenly no longer afford to eat it. While newer studies dispute this claim, both agree on one thing: the sudden popularity of quinoa has meant a huge increase in the number of people farming it, and a corresponding decrease in the diversity of crops produced.

The demand also led to changes in the way quinoa was farmed—it was traditionally grown on the terraces that characterise much of the Andean region, but these could not support the quantity of quinoa that the world suddenly wanted. The grain therefore spread to the flat regions on which llama herds had previously grazed, where tractors could be employed to till the fragile Andean soil. This both changed the balance that had existed for generations between agriculture and animal husbandry, and meant less manure was available to fertilise the fields. This led to soil degradation, which made it harder for smaller farms to exist—and this, in turn, led to the consolidation of farms in the hands of larger, better capitalised owners.

The way this story can end for indigenous people is captured neatly in a quote that appeared in a 2013 Washington Post article about quinoa, from one Sergio Nuñez de Arco, founder of a company called “Andean Naturals”: “It kind of hurts that the guys who’ve been doing this for 4000 years aren’t even present. ‘You guys are awesome, but your stuff is antiquated, so move over, a new age of quinoa is coming.’”

It kind of hurts. Kind of. (The company’s website, for the record, promises that its product “is cultivated by traditional smallholder farmers … who are committed to sustainably growing organic quinoa.” Hurrah.)

The story is much the same when applied to cacao, whose superfood status has led to deforestation to meet the resultant rapid demand.

Illustration: Iryna Zaichenko/iStockPhoto

Similar scenarios have started to play out in an Australian context. In 2018, Indigenous involvement within the native food industry, from growers, to business owners and exporters, was estimated to be only at 1%.

While this figure is likely to have grown since, it raises questions about who is reaping the rewards from traditional knowledge. Intellectual property is also a key factor in this area, as without care, Indigenous knowledge could be exploited and further taken away from the community.

There are also other factors. Most traditional Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander food is currently wild harvested, so prices are high and supply is limited. Finger limes, for example, sell for $40 to $45 per kilogram. This results in a familiar pattern: while high-end restaurants and the wealthy few can enjoy these “new” and “different” additions to their weekly menu, not all Aboriginal people are able to purchase foods their families have eaten for millennia.

The rapid growth in demand for Australian products, and the high price consumers are willing to pay, have sparked worries of a black market developing. Back in 2016, for example, 600 kg of frozen of Kakadu plums—worth $12,000—was stolen from Mayi Harvests Aboriginal Corporation, an Indigenous owned business based in Broome. The stolen gubinge was picked by traditional owner families, and given the nature of wild harvesting, it was unable to be replaced, disrupting the corporation’s relationship with its buyers.

For Arabella Douglas there is a distinction between white Australians learning about and appreciating Indigenous products, and the exploitation of that knowledge. The best way of walking this line is ultimately a matter for individuals, but some companies—including Currie Country—have decided that in order to help the Indigenous food industry flourish, they will share their sacred knowledge with selected chefs committed to Indigenous values and protecting the traditions behind the foods: “The chefs that were engaged and wanted to learn about [Indigenous foods] were committed to sustainable farming practices, understanding the sensitivity of land, knowing that land has energy and reverberates, and is a living being, and wanting to make order of that in their brain.”

This tension between seeking knowledge and exploiting it is one that manifests constantly when discussing the ways in which non-Indigenous Australians engage with Indigenous cultures. For example, growing native plants at home is one way for non-Indigenous Australians to learn more about the cultures that cultivated those plants—but as Douglas emphasises, harvesting and foraging Indigenous foods is protected as a First Nations right under international law: ‘The law allows me to operate [my business] and recognises my spiritual connection to food harvesting and food production, because all of those things carry totems, they carry spiritual connection … If you interrupt that, you’re interrupting [First Nations people’s] innate human right to operate in their fullest function.”

Respecting the sacredness of this practice is in many ways the least that non-Indigenous people can do to show their respect to traditional land owners. “Be an active buyer and a conscious consumer,” Douglas says, “but don’t try to exploit Aboriginal knowledge. Be OK that Aboriginal people have got that covered, and allow them to lead you.”

It is an indictment of white Australia that this concept—of being led by Indigenous knowledge, of respecting and listening to those with a deep and ancient connection to and understanding of this land—has taken so long to even occur to many of us, and even now feels revolutionary to so many. But if the reality of climate change makes one thing clear, it’s that the socioeconomic paradigms that have dominated the world since the colonial era—and the arrogance of the world views that have underpinned them—are fundamentally unsustainable.

Illustration: Iryna Zaichenko/iStockPhoto

For centuries, wealthy and powerful nations have sought to impose themselves upon other lands and other cultures, seeing both as resources to be exploited and consumed, rather than valuable and irreplaceable assets. If the human race is to avoid climate catastrophe—or even go some way toward mitigating its effects—we must make fundamental changes to the way we approach the world.

These changes require humility and a willingness to learn—and, in the case of the food Australians eat, that learning can be done from those who were here long before the first European ships made their fateful entrance into Sydney Harbour.

As Bruce Pascoe put it, “You can’t eat our food if you can’t swallow our history … You can’t have these products without our culture.”

Nornie Bero at Mabu Mabu.

Thinking big

The growing and harvesting of Indigenous foods can feel a long way from the hustle and bustle of Australia’s cities. However, even there, Indigenous-owned food businesses are slowly gaining a foothold.

One business putting Indigenous foods on the map is Mabu Mabu, a food shop and catering business in the Melbourne suburb of Yarraville. The shop grew out of a small stall at the South Melbourne market, and aims to share the flavours and dishes of owner Nornie Bero’s home on Mer Island in the Torres Strait. “I am very happy that people are learning and understanding Torres Strait Islander culture,” Bero says. “[Fostering that learning] is the biggest thing for me. I’m so grateful to be able to do that.”

Mabu Mabu means “help yourself”, and that sentiment permeates every aspect of the shop’s bright interior. From the mural on the wall showing three Indigenous women laughing over a meal to the shelves of products from other Indigenous-owned businesses, the store is all about community.

Bero says she enjoys surprising customers with the menu. “[Surprise] is a normal reaction because I think they just never think about [Indigenous foods],” she says. “Customers are really lovely, and they’re really open to trying whatever we put out. I think that is what excites me the most. [People] come to us because they want to try something different.”

The success of Mabu Mabu has seen Bero open an all-day restaurant and bar in Federation Square called Big Esso, slang for “the biggest thank you”. This thank you is not only to the customers that support her, but to the land she calls home. This idea of respecting and being kind to the land is also reflected in the menu of both Mabu Mabu and Big Esso—most prominently in the idea of eating seasonally. “I’m trying to … show our customers that you can only get things seasonally and grow from whatever is on the land,” Bero explains. “Why do we need to buy cherries this time of year from somewhere else? Enjoy them when the season is here, and be grateful for it.”

— Larissa Dubrowsky-Ryan

Further reading

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Gas and our health

Dr Ben Ewald uncovers the health effects of gas in the home.

Read more