Transmission and emissions

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

We need contingency strategies in case ‘big transmission’ is delayed

Apparently, we need to build 10,000 kilometres of new powerlines to support our renewable electricity revolution. But there are many technical and social license challenges. We need contingency strategies that can maintain reliable electricity supply if there are delays.

What could we do? First, we could drive energy efficiency and demand management harder, to get more services while using less transmission capacity. That should be a ‘no-brainer’. Heating demand for inefficient buildings and loads on transmission lines peak when we are short of variable renewables.

Second, we can drive local energy production, storage and smart management. Virtual power plants, community batteries and smart demand management, broadly described as distributed (or community) energy resources, are ramping up. But outdated energy market rules undermine progress. Matching seasonal solar generation to demand and maintaining grid stability can be challenging.

Beyond these options, we will need to be able to shift electricity between large renewable energy generators, users and storage. The mainstream global view is that we will need a lot of new powerlines.

The basic problem is that an unfinished powerline delivers no useful energy. Delays in roll-out create bottlenecks with serious economic and reliability impacts as new renewable energy generation cannot deliver useful electricity and the owners of those assets lose money. But powerline construction is complicated technically and socially, and the energy sector’s track record in building trust and social license is poor. Labour and material shortages add to challenges.

The ‘top-down’ solution is to offer compensation to those affected, or to bulldoze over their concerns in response to the broader societal interest. Neither of these is very satisfactory, and both can lead to long delays. The Snowy 2.0 debacle highlights the technical challenges of large-scale projects, while the costs and uncertainties faced by developers of solar and wind farms denied access to grid capacity are undermining investment in our urgent decarbonisation strategy.

The International Energy Agency has recently released a study of future directions for electricity grids. It acknowledges that grids will need to work in new ways, and that grids risk becoming the weak link in future energy solutions. What can we do if transmission line projects are delayed?

In addition to the measures outlined earlier, we can increase utilisation of existing powerlines. Most powerlines have relatively low average utilisation: they work hard at times of peak demand, but operate well below capacity for most of the time. Batteries well-managed and located strategically throughout the grid can smooth loads on powerlines while improving consumer reliability and voltage stability. Distributed energy storage can be ‘trickle charged’ to help manage peaks locally.

We will also need to consider ‘outside the box’ options. One potential option is portable storage. With modern high energy density battery technology, an electrically powered semi-trailer can transport a battery with several megawatt-hours of stored electricity to a major customer or part of the grid that has spare capacity or needs more power at quite low cost.

Trains towing batteries could transport a lot of electricity to where it can be used cost-effectively by consumers. Indeed, this approach could potentially be used by existing renewable energy generators that are being adversely impacted by AEMO limits on their electricity output. These portable batteries could also be handy after bushfires or floods, and they could be used during peak harvesting and processing in rural industries.

There is increasing interest in producing high temperature heat using solar energy: this can be transported to where heat would otherwise be produced from electricity.

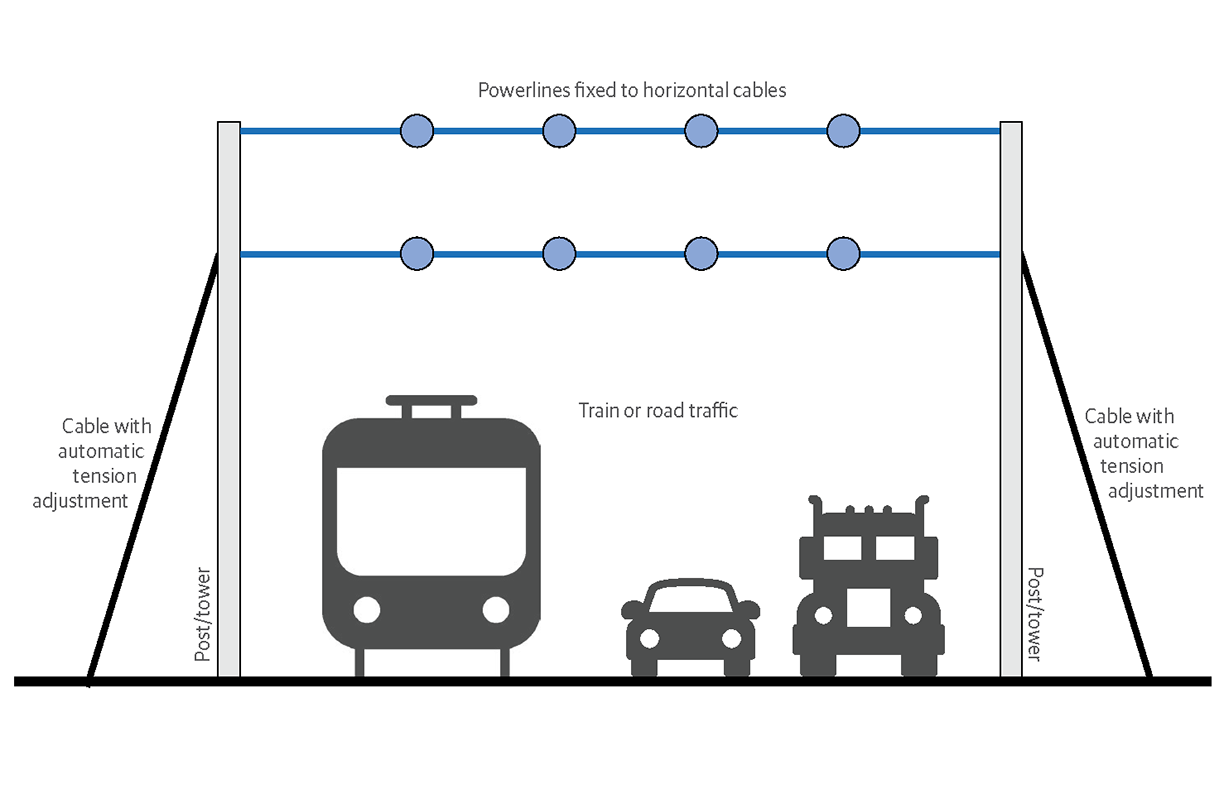

We could also question why powerlines must be installed on new ‘rights of way’ when we have roads and railway lines with existing reservations close to hotly debated new reservations for power lines. Surely we could design powerlines that use those existing reservations without creating safety or other issues? At present the debates seem to be about traditional above ground powerlines and expensive underground powerlines. Maybe neither of those is the solution?

We need creative solutions to overcome entrenched thinking. I am sure that others could come up with better ideas than I have. We need them!

Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions: who is responsible for what?

When an Australian buys a Barbie doll, most of the carbon emissions from its production are allocated to China or Mexico, the sources of their materials and manufacture. When a Japanese consumer burns gas imported from Australia, it adds to Japan’s carbon emissions: so, the Australian government sees no point in cutting fossil fuel exports, upsetting our powerful fossil fuel industries and reducing government royalty and tax revenues.

These outcomes result from the way international carbon accounting rules work. Each country is responsible for emissions directly produced from burning of fossil fuels and other sources of emissions such as agriculture and land clearing—known as scope 1 and 2 emissions.

In theory, if everyone was actively cutting emissions, all emissions would be included on someone’s scope 1 and 2 emissions. But that is not how it often plays out: high emitters shift responsibility onto their supply chains and customers, who often have little or no incentive to change, or may not be able to change.

There is increasing focus on these ‘scope 3’ emissions in voluntary carbon accounting schemes. It seems to be a matter of time before international mechanisms will be introduced. For example, the European Union is introducing ‘Border Adjustment Mechanisms’ so imported materials from countries without carbon taxes or pricing will have to pay so that local businesses that do pay carbon prices will not be disadvantaged. Australia should consider options to influence emissions from use of its exports, especially fossil fuels—and embodied emissions in imports we choose to buy. We are on borrowed time.

How do we balance local emission reduction with the ‘green superpower’ export vision?

For me, it is not an ‘either or’ issue. It is true that greening Australian exports of iron, aluminium and other materials, and growing our ‘value adding’ using renewable, high efficiency technologies can make a big contribution to global emission reduction, as emissions from customer countries burning our exported fossil fuels are much bigger than our own emissions.

This action may also reduce demand for our fossil fuel exports, but the impact on our economy may be smaller than many assume, because most fossil fuel exporters are internationally-owned, so we don’t capture their profits.

These industries can create new jobs in key regions to replace those lost as we phase out fossil fuel exports. They will help us to maintain our balance of payments.

But developing this option means we face serious competition with other countries. These include Asian countries, with low labour costs and capacity to distort global markets, and developed countries. The USA’s ‘Inflation Reduction’ policy is providing enormous subsidies to shift ‘green’ activity into the USA. European countries face extreme pressures to change, due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and associated reductions in energy exports from Russia, so they are ramping up subsidies and incentives.

But it’s also true that these export industries won’t create lots of jobs or reduce energy bills and emissions for Australians. Close to 90% of jobs and over two-thirds of our economy are in the services sector. Households matter a lot because we need to manage equity and quality of life: household decisions impact on much of the economy’s energy use and embodied emissions. And reliable, affordable ways of delivering energy services (not necessarily cheap energy) are essential to underpin our local economy.

So we need to drive both exports and local change, and to try to maximise the synergies between both to maximise overall benefit. We also need to help our Asia-Pacific neighbours to cut their emissions and build economies that will be viable in a zero carbon, global heated world.

At the same time, timid governments need to be reassured that they will maintain their ‘license to operate’ (that is, win enough votes to stay in power) as they pursue what’s needed. And Luddites must be outmanoeuvred. Easier said than done, given the enormous resources of vested interests, lobbyists and politicians ignorant of the laws of physics.

Further reading

Climate change

Climate change

Charting possibilities of the blue economy

Mia-Francesca Jones explores the opportunities of the blue economy for oceanic health, as well as human and planetary wellbeing.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy forecasts, hydrogen hype and questions of progress

Alan Pears gives us his round-up of the main energy issues this quarter.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy costs, climate impacts and quality of life

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more