Home truths: Notes from the assessor

After conducting home energy assessments for several years, Richard Keech shares some of the all-too-common problems he sees.

This article was first published in Issue 141 (Oct-Dec 2017) of Renew magazine.

Since mid 2015 I’ve worked doing building energy assessments in Victoria, mainly for homes and mainly on behalf of ecoMaster. In that time I’ve visited about 290 clients to inspect their premises. In this article I’ll try to convey insights about homes and energy based on my experiences. Some of this is specific to Victoria’s housing stock and temperate climate and some applies to all homes.

The assessment process itself

Winter thermal comfort is the biggest motivator in Victoria

I usually begin by asking clients what motivated their interested in an assessment. By far the most common response—probably three-quarters—is thermal comfort. Of that, most is winter thermal comfort. So whatever concerns people may have, it’s thermal discomfort that turns their interest into action. Given the current media discussion about energy costs, it’s interesting that cost is actually far behind thermal comfort in getting people engaged in the process.

People like to talk about their house

There’s an element of therapy about consulting on home efficiency that goes well beyond people simply receiving information about the state of their homes. It’s very much a two-way process. So patiently listening to people talk about how their home does or does not work seems to help people engage in the issue of home energy and comfort.

People don’t value professional advice highly enough

I’m very lucky to work for one of the few companies that consult on home energy efficiency. But even so, many people expect a lot for nothing, especially when it comes to draught proofing and general advice. Understanding a client’s home, sufficient to specify the many things typically needed to draught proof a home, is time-consuming.

The people who most need professional advice are the least likely to get it

A tiny fraction of households seek professional advice about their homes’ efficiency. And I expect that the homes we see are far from being the worst out there.

Tenants are missing out

Only a tiny fraction of our consultations apply to rented premises. Landlords and tenants both obviously lack the motivation to spend the money on a consultation because the cost and benefit incentives are misaligned. As a country we need ways to motivate landlords to improve their properties for the benefit of the tenants. This is worthy of a whole separate discussion; e.g. see this article in The Conversation and Energy-efficient renters in Renew 134.

The top things I’ve learned about homes

Newer homes often have poorer prospects than old homes

The older a home is, generally the worse its baseline thermal performance. However, newer homes often have worse potential for improvement for a number of reasons.

- Slabs: On-slab construction is much more common in recent years and it’s not practical to retrofit insulation to a slab as you can with many timber floors.

- Eaves: Current building practice is often oblivious to good passive solar design, especially when it comes to the use of decent eaves to help shade windows in summer.

- Dark roofs: The recent common practice of using very dark roofing colours is problematic for summer-time thermal comfort. There appears to be cultural resistance to light-coloured roofs.

- Hard-to-insulate roofs: Newer homes often have shallow-pitched or flat roofs which are hard or impossible to access for inspection and upgrading of insulation.

People often overlook split systems as an efficient heat source

Contemporary split system air conditioners make very efficient heaters. However, most people don’t realise this and, often, when a split system is present, it goes largely unused in winter in situations where it could save money and improve comfort. See ‘A tale of two heaters’ in Renew 133 and the All-electric special in Renew 140 for case studies.

Awareness is emerging of the problems with gas

Two years ago people were surprised to hear me explain the fundamental problems with using gas as a heat source. Today it seems the message comes as less of a surprise.

Fixing draughts nearly always gives the best bang for buck

The low-hanging fruit when it comes to fixing homes is nearly always the draught proofing. It’s often overlooked or done badly.

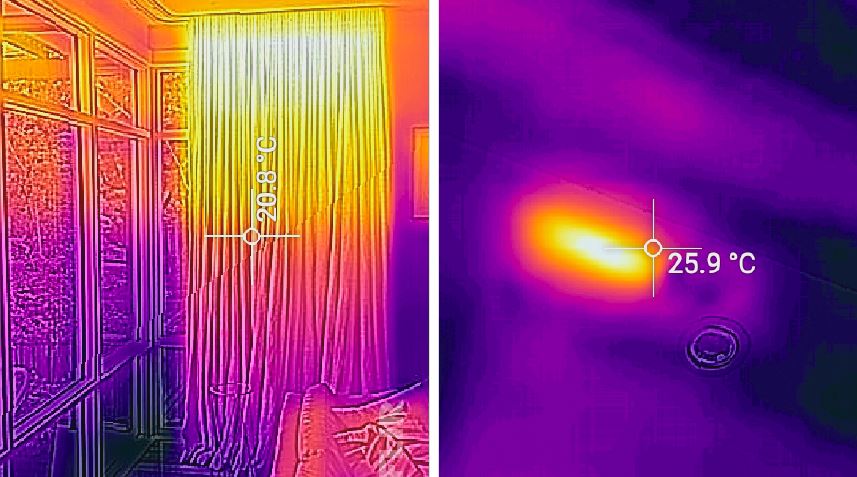

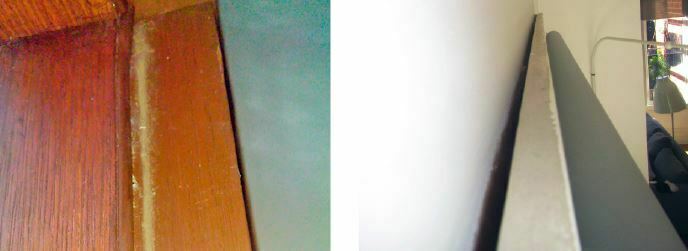

Warped doors render weather strips pointless

The common practice of putting weather strips in a door jamb is frequently ineffective because external hinged doors are often warped; the door aligns with the door jamb on the hinge side, but not on the latch side. This shows up as a gap between the face of a door and the door jamb at the top or bottom, or both. In such cases, weather strips are useless. The solution is to fit a seal onto the door frame which aligns with the actual warp of the door; for example, Draught Dodgers from ecoMaster.

Architraves are a common and overlooked draught source

Almost every home I see has unsealed gaps at the top of window and door architraves. Sealed architraves are necessary to keep doors and windows air tight. It’s a case of out of sight, out of mind.

Downlights are a blight

The problems with downlights have been discussed many times in Renew, but it’s worth repeating because it’s a big problem. Legacy downlights are typically associated with four problems. They have poor light efficiency (high energy use and often narrow beam angles); they often allow draughts; they always compromise the ceiling insulation; and the transformers they use are often very inefficient.

Fires are draught amplifiers

A working gas or wood fire consumes oxygen and produces flue gases. The flows in and out have to be in balance. As a result, operating a fire necessarily sucks air into a house. When you’re trying to heat in winter, the last thing you want is more cold air. So fires are actually a worse problem for comfort and efficiency than generally supposed because the heat generated is offset by the cold air drawn in.

Insulated ceilings are often performing at a quarter of the minimum recommended

The typical ceiling I see has insulation batts rated about R2. There are also significant gaps exposing the ceiling plaster, so the insulation performance is severely compromised, often by about 50%. Given that the recommended minimum level of insulation (in Victoria where I work) is about R4 that means most homes I see have ceilings operating at only about a quarter of the minimum recommended.

Watch out for asbestos

There’s a lot of asbestos in Australian homes. I see it most in eave panels, which are not a problem if left alone. However, it’s not uncommon to see fragments of asbestos under people’s houses, and householders and trades should be wary of this. Another source is old asbestos flues left behind in ceilings.

Hot water pipes are almost never insulated to code

I’ve come to realise that the requirements of the plumbing code regarding insulation of hot water pipes are almost universally ignored by plumbers. Nearly all (>95%) hot water pipes I see are completely or practically uninsulated, whereas they should have proper pipe insulation fitted. This common practice results in homes using more hot water than they need and thus wasting energy. For long pipe runs, it can also mean that the temperature drop is too great and the occupant has a poor experience in the shower. Note that the commonly seen hard green plastic coating often seen on hot water pipes does not count as insulation!

No love for ducting

There’s scope for a whole article on the problems with the effectiveness and efficiency of ducting. However, my assessments reveal three main problems.

Ducted evaporative coolers are a problem:

Even when fitted properly and in good condition, ducted evaporative systems can seriously compromise ability to heat a home in winter. Mostly in older units, hot air leaks back out through the vents (though modern evaporative systems have back-draught protection built in). In addition, the presence of the ducts and vents also tends to compromise ceiling insulation.

Ducts can be unsealed or uninsulated without people realising:

It’s not uncommon to see ducting in poor condition and spilling conditioned air into the ceiling or subfloor space. Furthermore, if the ducting isn’t airtight then it presents an unwanted draught pathway via the vents when the air conditioner is off. Sometimes I see ducting where the outer plastic layer has deteriorated which allows the insulation layer of the duct to fall away, leaving the ducting completely uninsulated.

In-ceiling ducted heating is often problematic:

It’s surprisingly common to see homes with ducted heating configured with both vent outlets and return-air vent at ceiling level. Configurations like this are problematic because warm air entering at ceiling level usually can’t mix down to floor level, causing stratification of the air, especially in homes with tall ceilings. This makes the systems both less effective and less efficient. Occupants will perceive this most directly as ‘cold feet, hot head’.

Case study: Shooting the breeze

Comprehensive draughtproofing was just the first recommendation that came out of Annie and Bob’s home energy efficiency assessment, but it’s already made a huge difference to the thermal comfort of their house, as they explain to Anna Cumming.

Annie Cvetkovic and her husband Bob live in a three-bedroom brick veneer unit in Burwood, in Melbourne’s eastern suburbs. It’s only around 30 years old, but according to Annie it’s only comfortable to live in during autumn and spring. “In summertime it is unbearably hot, with no proper insulation designed to keep the heat out. We actually can’t live in the back part of the unit—the spare room and study—during the summer.”

And in winter the unit is very cold, despite gas ducted heating. Annie and Bob are getting close to retirement, but still both work and are otherwise active outside the house most days.

“A major issue for us is walking in the door at the end of the day, and the place is so freezing. It just didn’t feel right,” says Annie, explaining why they decided they needed to make some changes. “I found myself having to sit with my feet up on the couch because it was cold underfoot.” They also wanted to make the house more comfortable so that they can feasibly stay in their home as they age.

Annie and Bob’s unit is only about 30 years old, but it wasn’t built to perform well thermally. They are planning to upgrade it in order to live more comfortably in it as they get older.

They employed Richard Keech of ecoMaster to conduct an energy efficiency assessment, which resulted in a prioritised list of actions they could take to improve things.

“We originally thought we’d start with double glazing,” says Annie, “but Richard convinced us that that’s actually the last thing to do!” The advice was to start with draughtproofing, then underfloor insulation, followed by wall insulation pumped or blown into the wall cavity—particularly for the north-west facing back wall which makes the spare room and study so unusable in summer.

Upgrading the ceiling insulation would be next, “and only then should we consider double glazing, and possibly a small split-system air conditioner in the back room, if we find we need them.”

So far, they have had draughtproofing installed where it was needed—mostly in the gaps between architraves and walls, and around doors and windows using a product called Draught Dodgers (supplied by ecoMaster). They have already noticed a big improvement.

“I didn’t know how dramatically draughtproofing would change the comfort level of the house,” says Annie. “It’s not nearly so cold when we walk in at the end of the day. The ambient temperature is probably two or three degrees higher without any heating.” They are having to use their heating less.

Annie and Bob are planning to work through the rest of the recommendations from the assessment as they find time to organise them and are looking forward to the even greater improvements in the thermal comfort of their house.

Following their home energy assessment, the first step for Annie and Bob was to install draughtproofing. Draught Dodgers stop airflow around the edges of doors and casement windows when they are closed; the product consists of a metal strip attached to the frame, with a flexible rubber seal against which the door or window closes.

This article was first published in Issue 141 (Oct-Dec 2017) of Renew magazine. Issue 141 is our energy efficiency special.

Recent articles

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Ditching the shower fan

By fitting a lid on the shower, exhaust fans are not needed when showering. John Rogers describes this simple retrofit, using both a commercial product and a great looking DIY version.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Remote communities leading the charge

We learn about four sustainability and renewable energy projects in remote Australia.

Read more