A new lease on sustainability

“If anything good comes out of this…” is a phrase everyone is sick of hearing—but as Rob McLeod argues, it’s imperative that at least one good thing has to come out of Covid: getting rental homes up to scratch.

Few people in Australia have been untouched by the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic: effects on our health, financial security, relationships and general wellbeing. However, the pandemic has hit renters particularly hard, amplifying the inequality that has long existed in our housing system.

If you rent in Australia, you were most likely already living on a short lease, offering limited rights over how you live in your home. That situation is now more precarious.

While protections are currently in place for renters who have lost income due to the pandemic, many have good reason to fear what might happen when temporary bans on evictions, rent increases and utility disconnections are lifted. Some renters and landlords have negotiated rent reductions in good faith; many have not, which serves only to reinforce the unequal power dynamics of such relationships.

Most of the focus on renters during the shutdown, both from governments and from the media, has rightly fallen on keeping people in secure housing. But as well as reminding us of the inherent inequalities in the landlord/renter relationship, the pandemic has also been a sharp reminder that millions of existing homes in Australia are simply not up to scratch.

Rental homes are, on average, less energy efficient than owner-occupied homes. This means that many renters are left paying high bills and living in unhealthy homes. Staying at home comes at a high price if your home is cold and damp because your landlord refuses to seal gaps or install insulation.

Making rental homes healthy and resilient in the face of climate change is more important now than ever—and the recovery from the coronavirus pandemic might be the best chance we ever get to do it.

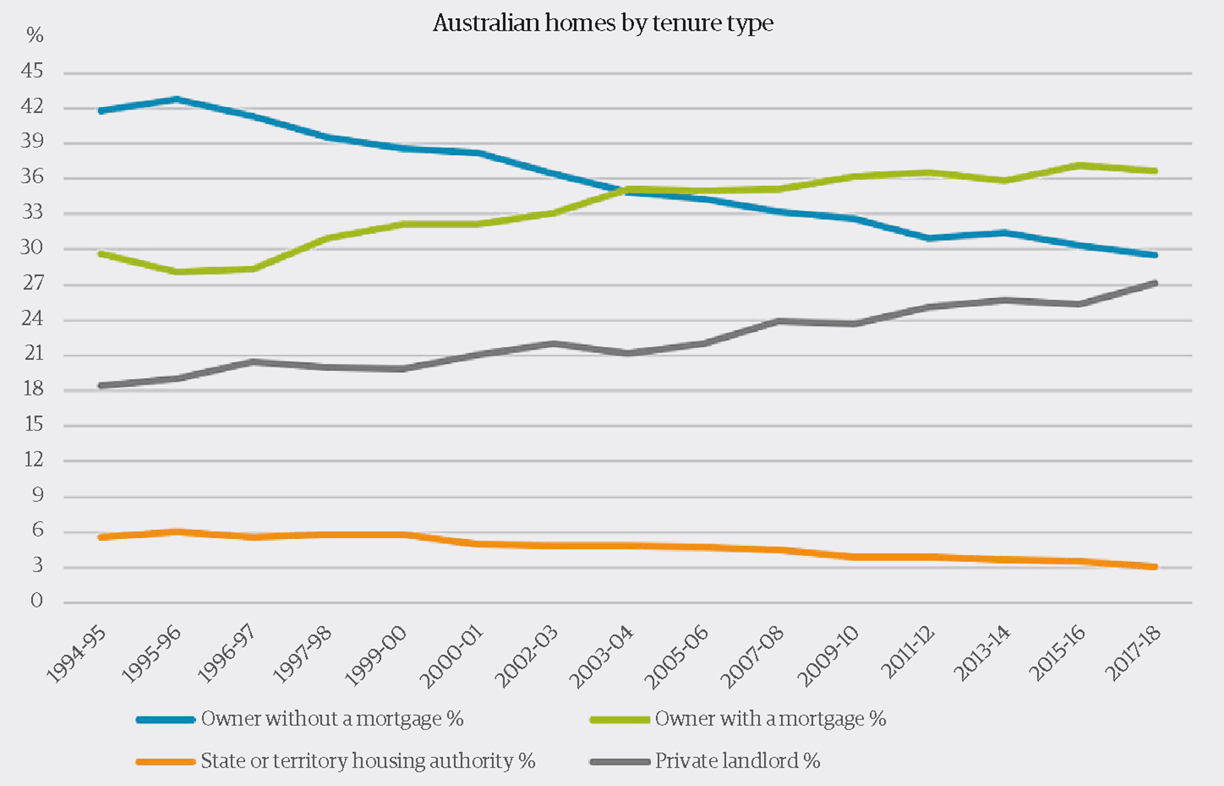

Source: Australian Bureau of Statistics

Renting in Australia

Nearly one in three homes in Australia is rented, and as the chart above demonstrates, that number is rising. As the rate of home ownership declines, the proportion of people renting is increasing steadily—from 26.3% in 2001 to 30.9% in 2016. This trend is not a coincidence: more people are renting as the housing boom has driven the cost of buying a home out of reach.

Tenancy laws and protections haven’t kept pace with the growth in renting. The Australian housing system has tended to treat renting as a temporary arrangement—a step on the way to the Australian dream of owning a home on a quarter-acre block. In 2020, however, people are renting for longer, and a growing number of people are expecting to do so permanently.

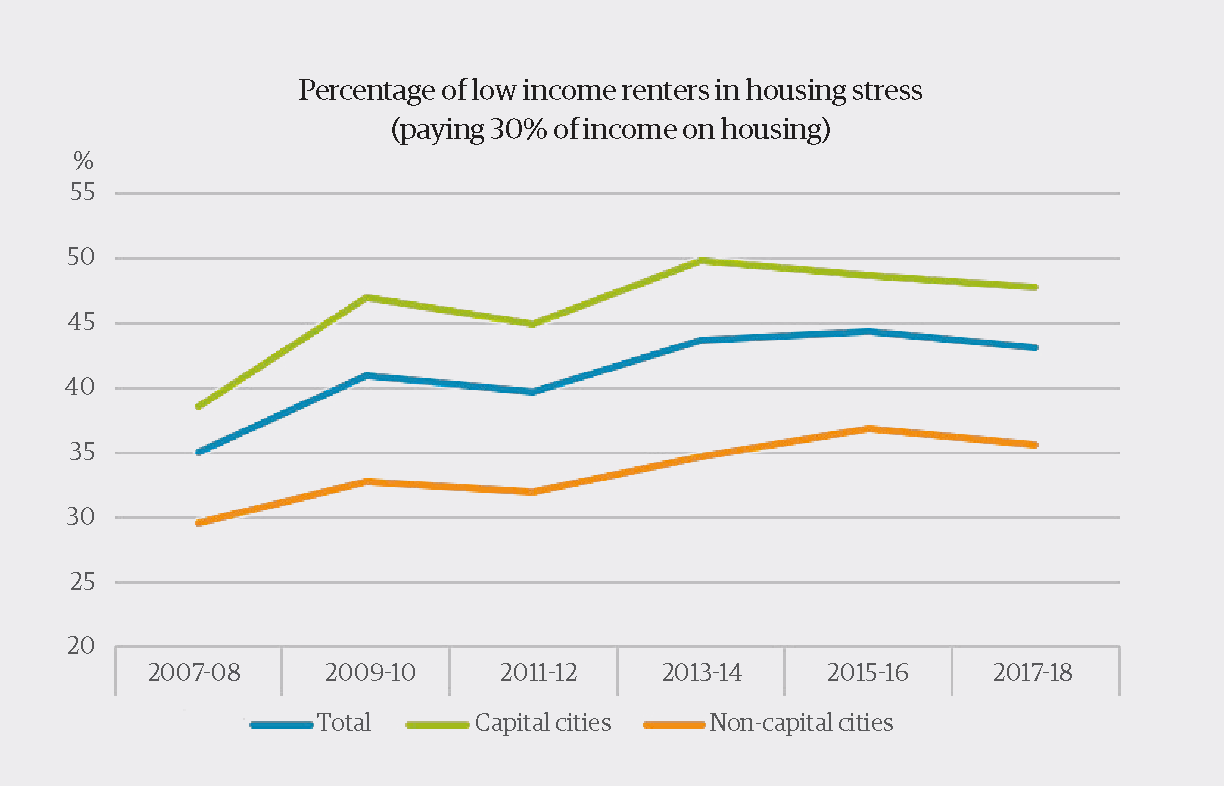

This means that more and more people are being put under long-term pressure by the downsides of renting—insecure 12-month leases, unpredictable rent increases, and minimal rights to adapt homes. Rental prices have fallen in many areas during the coronavirus pandemic, but only after rising significantly in real terms over the last 20 years. For renters on higher incomes, these increases may be manageable, but the ever-growing costs have put people on low incomes under significant housing stress.

Anglicare has found that fewer than 1% of rental homes in major cities are affordable for people whose main source of income is government support; little more than 20% of rental listings are affordable for people earning the minimum wage.1 (It should be noted, however, that the research in question was carried out before the introduction of the temporary coronavirus payment.) The proportion of renters paying more than 30% of their income on rent—the point that the ABS considers the boundary of experiencing “rental stress”—was up to 11.5% in the 2016 census. With investment in non-market social housing significantly lower than comparable countries, waiting lists for public and community housing are blowing out to the point where applicants wait years for a home. The result: over 100,000 people around Australia are homeless at any given time.

The coronavirus pandemic has cast a spotlight onto the precarious housing situation that is a fact of life for millions of Australians. Mass job losses have not resulted in mass homelessness because of a combination of voluntary rent reductions and eviction bans. But voluntary reductions are just that: voluntary. They mean that renters experiencing financial difficulty because of the pandemic are left relying on the largesse of landlords, with predictable results: a recent survey in Melbourne found that more than half of renters who had lost income were unable to secure a reduction in rent.3

With the bans on evictions set to end over coming months, tenants who have been unable to pay their full rent over recent months have good reason to feel nervous about what happens to their tenancy when it is no longer formally protected. Meanwhile, those whose landlords would agree only to rent deferrals, rather than reductions, are left with mounting debts at a time when the economy has definitely not returned to anything vaguely resembling “normal”.

Images (clockwise from top left): Almira Forsyth/Flickr, Salim Virji/Flickr, Joanna Bu/Pexels

Rental homes are less healthy and cost more to run

On average, rental homes in Australia have worse energy performance than owner-occupied homes.

A big part of the reason for this is that landlords simply don’t have the same financial incentive to upgrade rental homes that owner-occupiers do. If you live in a house that you own, energy upgrades are a win-win-win: your initial outlay gets you reduced energy bills, reduced emissions, improved health, and the knowledge that you’re reducing pressure on the energy grid.

For rental homes, however, landlords meet the upfront costs of energy efficiency improvements while it is renters who receive the benefit of reduced power bills. The converse is also true: if a landlord wants to avoid paying the upfront costs of maintenance and upgrades, it is renters who end up paying for this inaction in the form of higher bills, as well as less tangible impacts: the health effects of damp and mould, reduced productivity because of hot sleepless nights in summer, and many more insidious effects that hide in plain sight, accepted with a shrug as the consequences of living in a rental.

The result is that many homes are simply not fit for purpose: they are cold in winter and hot in summer, and/or suffer from draughts, inefficient appliances, lack of insulation, poor thermal shells, and inefficient hot water services.

As of 2015 in Victoria, 42% of private and 45% of public rented homes had no insulation, compared to only 5% of owner-occupied homes.4 Similarly, the ACT’s nation-leading energy rating disclosure system has showed that one in four renters live in an uninsulated home with the lowest possible rating of zero, compared to one in 20 owner-occupiers.4 At the bottom end of the market, key features are missing altogether. In cold Victoria, 9% of rental houses and 14% of rental apartments have no heating at all.5

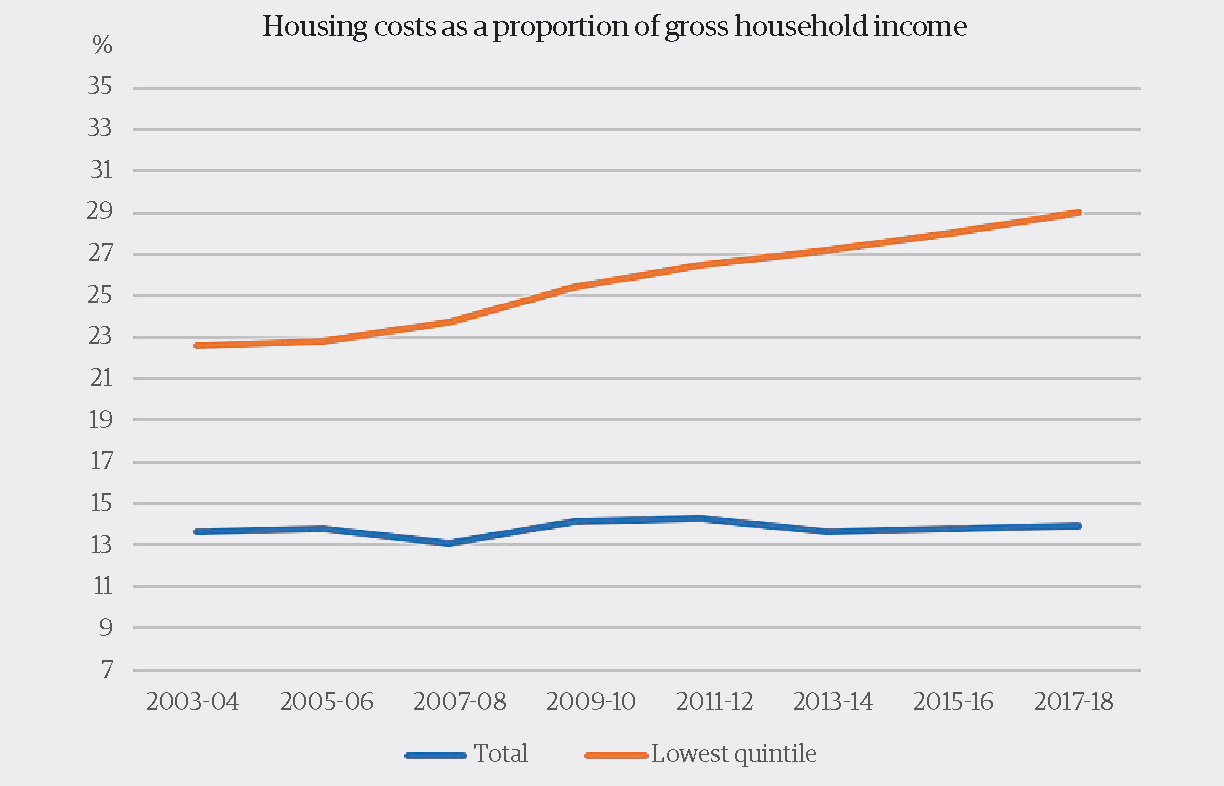

People on lower incomes are also more likely to own older and less efficient appliances, a classic demonstration of how it’s expensive to be poor: being unable to afford the initial cost of a more efficient appliance leaves you paying larger electricity bills in the long run.6 Poor energy performance compounds the energy stress experienced by people on low incomes, who are disproportionately likely to rent. People on low incomes pay a significantly higher proportion of their income on energy costs than others. In 2018, the 20% of households with the lowest income paid 6.4% of their income in energy expenditure—up from 5.9% ten years earlier. The top quintile, meanwhile, paid only 1.5% of income on energy expenditure7—another demonstration of how costs that are insignificant for the rich can be calamitous for the poor.

Unaffordable energy costs lead to households rationing energy consumption, including avoidance of using heating and cooling—with potentially dangerous and serious consequences for health.8 Illnesses relating to cold exposure are overwhelmingly a result of inadequate protection from the elements in the home. The poor condition of Australia’s homes was reflected in a 2015 Lancet study that found that more people in Australia die of cold-related illnesses and exposure than in Sweden.9

Decent landlords might be responsive to requests from tenants to improve the energy performance of a home, but there is no requirement for them to do so. In practice, few renters feel secure enough to request voluntary spending on energy upgrades or maintenance for fear that this may impact their tenancy. Even where landlords do see the benefits of energy upgrades, specific disincentives remain. For example, tax deductions are available for like-for-like replacement of items due to regular wear and tear, but not for energy efficient upgrades. Perversely, in some cases owners can receive a tax deduction for installing an inefficient appliance but not for an efficient one.

Renters also face limits on the practical actions they can take to reduce household energy use. In most states and territories, explicit permission is still needed from the homeowner for tenants to make any sort of alteration — so if your landlord says you can’t seal gaps or install shading, too bad. But permission isn’t the only barrier. Upfront costs are often prohibitive. If a rental household had a secure long-term lease, they might reasonably choose to undertake projects in the home that could be certain to pay for themselves over a number of years, even if they could not enjoy the benefits of increased resale price that accrues to owners. But without the security of long-term tenure it makes little sense to install upgrades that would stay with the home even if you need to leave—or if, having installed such upgrades, you suddenly find that the landlord wants to terminate your lease… and you find the property back on the market for a higher price, with a placard outside boasting of energy efficient upgrades! (This is a key reason why it is important that the responsibility for upgrades and maintenance remains with the landlord.)

Leaving rental standards to market forces won’t resolve these problems—but we haven’t even tried that. The consumer information that would allow prospective renters to choose more energy-efficient homes is inadequate or simply unavailable.

This year, Environment Victoria conducted “secret shopper” research by attending open-for-inspections to ask real estate agents simple questions about the energy ratings of the home. Overwhelmingly, agents were unable to answer: only 9%10 of agents were able to state an energy rating for the home.

So, as a renter, you can’t find out how efficient your home is before moving in; can’t get permission to make simple fixes; can’t afford major upgrades; can’t be sure you won’t be kicked out after paying for a long-term improvement; and can’t complain to anyone who will enforce your rights if you are. Is it any wonder that renters are stuck paying high bills to live in unhealthy homes?

Time for change

Voluntary upgrades from landlords and tenants can make an important difference and bring down emissions. But leaving it to individual landlords and tenants to bring rental homes up to scratch is not enough. Governments need to change the rules of renting.

A key tool available to governments is to set minimum energy performance standards that must be met by all rental homes. State and territory governments are taking tentative steps in this direction.

The Victorian parliament passed legislation in 2018 that allows for minimum energy efficiency standards. While the standards have not yet been made public, it’s likely that the benchmark will be set at a low level; the regulations will require heaters to have a minimum rating of two stars and will not address insulation, hot water or cooling. What’s more, the regulations were set to come into effect in mid-2020, but were delayed on the grounds of prioritising other responses to the coronavirus.

The ACT government has flagged its intention to legislate new minimum energy standards for renters to come into effect by 2022-23, including a requirement for insulation. Other states, however—including Queensland and NSW—are currently regulating new rental standards that do not include energy efficiency requirements.

These plans are a step forward, but they fall short of what is possible. For comparison, new laws came into effect in New Zealand in 2019, requiring all rental homes to have floor and ceiling insulation—a subject not addressed in any current Australian rental regulations. The laws also set minimum R-values for insulation effectiveness and require a higher standard if new or replacement insulation is installed.

The various energy ministers in the Council of Australian Governments have agreed in principle to develop a national framework for minimum rental energy standards through the Trajectory for Low Energy Buildings policy process. But without strong pressure for change, there is a risk that any national framework will find the lowest common denominator: minimum standards that are easy for all states to agree to precisely because they will have minimal impact.

The benefits of strong rental standards far outweigh the costs. The NSW government has estimated that if all rental homes were brought up to basic energy standards, NSW renters would save $987 million from electricity bills over 30 years—a change that would pay for itself many times over in economic benefits as well as contributing to reduced emissions. Stronger benchmarks would lead to bigger savings for tenants.

Other policies are on track to complement minimum rental standards, including better ratings tools and the provision of better information to renters about the standards of their homes.

Building back better

If there is a silver lining to the coronavirus pandemic, it is that it provides a major opportunity for a green recovery.

In the 1930s, the world learned that the answer to mass-scale unemployment was not government cost-cutting, but rather greater government borrowing and investment to get people back into work and back to economic activity. The pandemic has put us in a situation that calls for similar economic measures. With large numbers of Australians out of work and economic activity in freefall, government stimulus will be needed to get people back into jobs. And there is a strong case those jobs should tackle the overlapping crises of inequality and climate change.

There are few better ways that governments could create jobs than through making large scale improvements to Australia’s housing stock, rendering it energy efficient and resilient in the face of climate change.

Renew has joined with over 50 community organisations to call for a National Low Income Energy Productivity Program. Our plan is a blueprint for energy upgrades to up to 1.7 million homes for renters, social housing residents and low-income homeowners.

A rental retrofit program—alongside construction of world-class, energy efficient social housing—could kickstart jobs in a post-coronavirus construction industry and tackle Australia’s ongoing social housing crisis. What’s more, investment in energy upgrades and 7+ Star social housing would equip the construction industry with the skills and knowledge to roll out higher energy efficient building practices in the private housing market at low cost.

The Million Jobs Plan developed by Beyond Zero Emissions sees home retrofits as a major source of green jobs, estimating that a major retrofitting program could employ over 100,000 people.11 There would be massive flow-on effects from these jobs in our communities, as well as the direct benefits to residents and emissions reductions.

By combining regulations on energy performance standards with direct government investment in retrofits, we have a genuine opportunity to transform rental housing. It is imperative that we take that opportunity.

Read Renew’s full plan for a National Low Income Energy Productivity Program at https://renew.org.au/advocacy/nlepp

Further reading

Energy assessments

Energy assessments

Lessons from an energy expert

The best way to do energy efficiency upgrades to your home? Call an expert before you start, writes Greg Howell.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Getting on board with the energy transition

Alan Pears gives us his round-up of the main energy issues this quarter.

Read more ReNew

ReNew

Why can’t we have true low-cost housing?

The cost of housing has risen so rapidly in Australia that many have been priced out of the housing market, with Australia having some of the highest housing costs in the world. But there are some cheaper options we could utilise. Lance Turner investigates.

Read more