Swings and roundabouts

Rachel Goldlust explores the “potted” history of gas stoves—with an environmental twist.

The recent preoccupation with electrification, spurred in part by Saul Griffith’s “Electrify Everything” campaign rolled out in 2022, has governments, communities, councils and households looking at the humble domestic stove and figuring out ways to make the switch. It’s worth looking back at the history of stoves, and where this current development sits in the grand sweep of time, as we adapt our living and cooking once more to a new technology.

The history of gas stoves in Australia also has a surprising environmental inclination as, much like now, 19th century designers were responding to growing concerns about air pollution, deforestation and climate change as they turned away from the previously popular coal stoves.

Metal stoves, such as the one invented by Benjamin Franklin in 1742, were increasingly common across North America and Britain in the 18th century, but were often designed for heating and not cooking. The Franklin stove featured a labyrinthian path for hot exhaust gases, allowing heat to enter the room instead of going up the chimney. As the main source of heating for 150 years-plus, coal stoves came in all sizes and shapes, with different operating principles. Since coal burns at a much higher temperature than wood, coal stoves needed to be constructed to withstand the high heat levels.

Although experiments designing a cooking stove fuelled by gas had begun earlier, it wasn’t until the 1880s that gas stoves began to be accepted as an appliance for cooking food, and early models had no automatic temperature control or insulation. The introduction of the gas stove was a big relief for Australian housewives who had largely managed the most essential task of lighting and maintaining the kitchen fire. According to historian Ann Delroy, as gas stoves came on the market, there was a widespread fear that gas would taint the food, that it would not cook as well as the tried and trusted wood and coal-burning stoves, and that gas stoves might explode. Sound familiar?

Gas stoves were being advertised as early as 1853 but were seldom used due to slow imports and high tariffs until the early 1870s. In 1873, the Sydney Morning Herald reported that “gas cooking stoves have to some extent been erected in this city during the past two years. In England they have been adopted in private houses, and in hospitals and other public institutions.” Also featuring prominently at the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition in 1888, one article remarked, “Victorian manufacturers seem to have devoted much attention, for all kinds and sizes of ranges are displayed by quite a number of firms, and the Metropolitan Gas Company also exhibit an extensive variety of gas stoves.”

At the turn of the century, gas stoves were box-like with burners on top, an oven below and a griller beneath the burners. Before the introduction of the thermostat, gas ovens had two burners, one on either side at the bottom, and a flue at the top of the back panel. Hot air passed directly from the heat source to the flue. Some early models had a damper in the flue, copying the principle of the solid fuel stove where it reduced the rate at which the fuel burned. They were constructed of black cast iron and were almost as difficult to clean as the cast iron wood-burning stoves. The ovens were mostly lined with enamelled panels that held in the insulation fibre and were not designed to ease the task of the housewife. There was little financial incentive for manufacturers in Australia to spend time and money improving the technology, as gas stoves had no serious competitors until the 1930s.

The gas stove quickly became a “domestic treasure,” with a flame that could be altered to suit the different “operations” of “roasting, baking, grilling, toasting, frying, or heating irons.” This new technological advancement was applauded as an efficient labour-saving device that also looked sleek and modern. It was also quickly adapted by Australian manufacturers. The ‘Early Kooka’ range was developed by Metters, a company established by Frederick Metters in Adelaide in 1891. The first design patented was the “top-fire” fuel stove, with a firebox located between the oven and the cooktop. Metters produced its range of stoves in three states, since moving heavy iron across the country by horse and cart was prohibitively expensive.

The name “Kooka” and the image of the Kookaburra identifies these stoves as distinctly Australian. The name came about as their ‘kitchen range’ relaxed into being termed the ‘kitchen cooker’ from which Metters’ ‘Kooka’ was a pun; matching its pictorial pun referencing, “the early bird catches the worm”. The company slogan was, “There is a good stove, And a better stove, But the best stove, Is a Metters stove.”

Technological advancements came slowly compared with the rapid changes made in the post-war period. Improvements saw the stoves lifted off the floor on legs, and advances in technology allowed the whole body of the stove to be enamelled. After the war, all-white enamelled, streamlined, pressed-steel stoves were common. But it was not until the 1940s, when the threat of competition from electricity for the cooking market galvanised the manufacturers into action, that stove design was considered seriously. By the 1950s, electric cooking began to be promoted as quicker, cleaner, better and cheaper to operate.

What about electric stoves?

The world’s first patent for a household electric stove was issued to David Curle Smith—a Municipal Electrical Engineer responsible for generating and supplying Kalgoorlie’s electricity—in November, 1905. About 50 appliances were then built and leased to customers in the following years. The design lacked a thermostat—the temperature was controlled by the number of elements in use. In 1906-07, the Western Australian gold mining city of Kalgoorlie thus became the first place in the world to see an electric stove manufactured with the intention of bringing “cooking by electricity… within the reach of anyone”. The ambitious enterprise also brought about the publication of Thermo-Electrical Cooking Made Easy by Helen Nora Curle Smith (incidentally the aunt of Sir Keith Murdoch, father to Rupert).

Curle Smith lodged a patent application for his stove in November 1905. The story of the first patent is usually credited to Lloyd Copeman (Linda Ronstadt’s grandfather), but he lodged his patent ten years after, and then sold it to Westinghouse. Although the first electric cooktops were introduced at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, they were largely inaccessible due to high purchase costs, a lack of grid connection and high electricity rates. Though cooking in electric ovens was advertised from the outset as “cleaner and more efficient”, in the 1920s only 34% of all houses in Victoria were wired for electricity.

Gas was available to many more Australian homes and consequently gas stoves, which were cheaper to purchase, cheaper to run, and required no installation fee, sold in greater numbers than electric stoves. Metters had been manufacturing a range of Early Kooka electric stoves since the 1930s that could be used “with all types of electric current” and were starting to be seen as convenient. Electricity was advertised as “efficient” and “modern” since it could be obtained at the flick of a switch, and it was clean, because there was no longer any need for dirty fires and therefore it was healthy and hygienic. Although 80% of homes in Australia were wired for electricity by 1947, an estimate of electric stove ownership indicates that only 36% of homes had electric stoves in Brisbane, 25% in Sydney and 24% in Melbourne by 1955.

Electromagnetic induction, the invention of electricity generated by magnetism, emerged thanks to the British Michael Faraday in the second half of the 19th century. In 1953 American Donald Stookey discovered glass-ceramic surfaces that feature coiled metal elements underneath tempered ceramic glass that are heated electronically. Electromagnetic induction works instead with powerful, high-frequency electromagnets that generate a magnetic field that turn the pan into the heating element, rather than the surface of the cooktop. This, in turn, requires cookware that has a magnetic field, such as iron, cast iron or enamel.

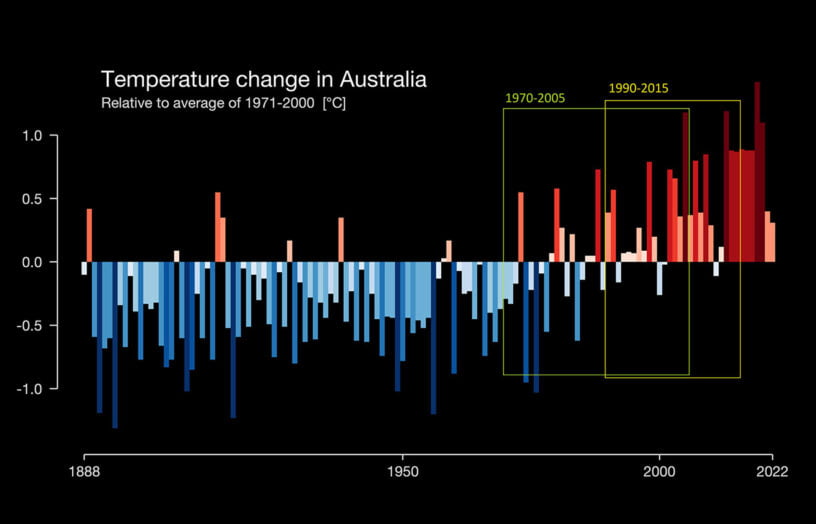

In the 1970s, the NSW Electricity Commission published a series of electric cooking recipes based on 15-minute daily television segments it produced called Switched on Living. This campaign had been running since the late 1950s and provided cooking recipes for households, often featuring the electric frypan. In the late 1980s and 1990s, home appliances started to be recognised within discussions around energy efficiency. New research was uncovering how home appliances were a major source of electricity consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. The relative inefficiency of various electric appliances was being remedied slowly, but the relative use of gas versus electric stoves did not change dramatically.

Now facing a renewed push to get off gas, we are looking to a future that will adapt our living practices and once again embrace electric appliances, particularly induction stoves. Much like the messaging in the 1890s, and again in the 1950s, it is all about being modern, efficient and healthy. History repeats as we learn to adapt to a changing health and energy landscape.

Further reading

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Gas and our health

Dr Ben Ewald uncovers the health effects of gas in the home.

Read more