Keeping cool – case studies

Using solar generation to pre-cool

A couple of years ago, Jasmine and James finished a renovation and addition to their freezing, draughty weatherboard cottage in Melbourne’s north. The project involved a passive solar extension to the north containing a new living space and kitchen with two bedrooms upstairs. It’s well-sealed and well-insulated, and contains plenty of thermal mass—including phase change material in the walls of the upper level. The retained part of the house was also upgraded, with wall and underfloor insulation, new floorboards and double glazing.

At 7.9 Stars, the house generally performs well thermally without much active heating and cooling, but in very hot weather, the couple operate the house like a ‘thermal battery’, running their air conditioners during the day to cool down the thermal mass and the phase change material, then turning them off to allow the stored ‘coolth’ to regulate the internal temperature into the evening.

“We have Daikin reverse-cycle air conditioners, the most energy efficient on the market at the time of installation,” says Jasmine. “A 5 kW unit in the dining area and two 2.5 kW units in the upstairs bedrooms.” (There’s also an older unit in the lounge, retained from before the renovation, but they only use that when they’re home as it’s less efficient.)

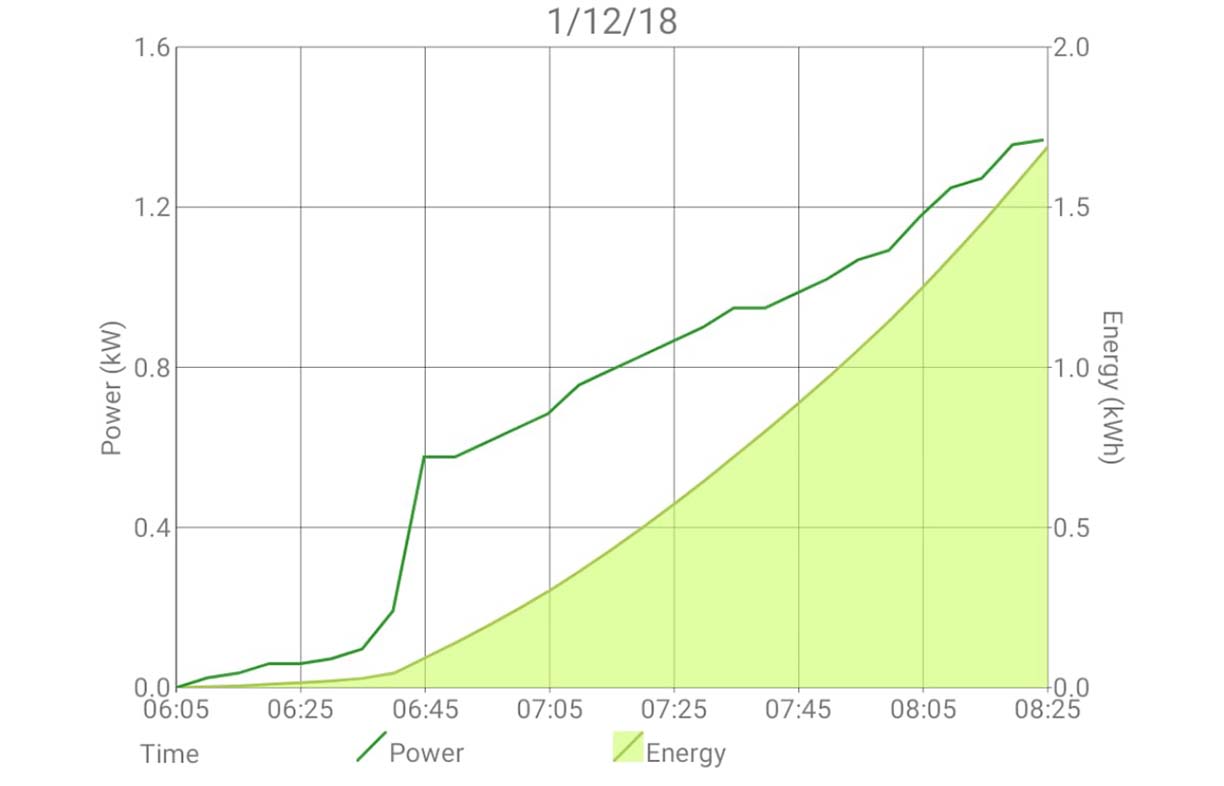

Jasmine explains that on days forecast to be over 32 °C or so with no cool change in the evening, they switch the air conditioners on when they leave the house around 8am, setting them at 24 °C and on the lowest fan setting. “The sun is well and truly up by 8am in summer, and our 4.7 kW of solar panels face east and west, so they are already generating,” Jasmine says.

They switch the cooling off at dusk, using ceiling fans through the night if necessary, and have found that even on very hot nights the ambient temperature downstairs barely changes by morning; upstairs in the bedrooms it will rise by only 2 °C to 3 °C.

“We don’t pre-cool if it is going to cool down in the evening—we just wait for that and open up the house to purge the warm air,” says Jasmine.

Pre-cooling with solar generation is working for this family, and last summer, their quarterly electricity bill was just $20.30 to power the whole house.

Minimising air conditioner use in the tropics

Having moved to Darwin from Germany six years ago and after living in different types of rental houses, Chris George and his partner knew what they were looking for when they were ready to buy their own home two years ago. “We found that the elevated house was best for liveability in the tropics,” says Chris.

Built to post-Cyclone Tracey specifications in the early 1980s, their house is around two metres off the ground on concrete piles, and is of timber-frame construction, with metal external cladding, plasterboard inside and no wall insulation. “It has a lot of louvres, which help with constant airflow through the house. Due to the light construction, it heats up quickly, but cools down even quicker,” Chris says.

The house has four reverse-cycle air conditioners: 2.5 kW units in each of the three bedrooms (two Fujitsu and one energy-efficient Daikin, which Chris installed to replace an existing one that failed) and an 8 kW Mitsubishi unit in the open-plan living and kitchen.

The family are not big air conditioner users. “We don’t really use the units in the dry season, we just open the windows and use our fans. In the wet season, we run the living room air con for 4 to 5 hours on weekend days (on the ‘quiet’ setting at 24 °C) and sometimes in the evenings during the week, depending on how humid it is,” says Chris. “We also run it in our baby son’s room overnight from 7 pm to 7 am with a temperature set to 26 °C, basically just to reduce the humidity. We cool our bedroom for about 15 minutes at 24 °C, then switch off the air con and use the fan.”

Chris explains that two main factors affect their cooling needs. Firstly, they installed large shade sails on the sections of the north wall that were not already shaded by garden trees. The sails shade the whole wall, not just the windows, and reduce the solar gain on the building. This has been a very effective strategy; Chris says that when one of the sails was damaged in a cyclone earlier this year, the house was noticeably hotter inside and their air conditioner use went up.

Secondly, they have the air conditioning systems cleaned thoroughly twice a year, at the beginning and end of the wet season; this involves taking apart the indoor units and cleaning each part, and the outdoor units get a very good clean too. The process takes about three hours per air conditioner. “If the airflow in the evaporator is blocked, the unit needs more power to reach the set temperature, or just isn’t effective.” He notes that in the high humidity, if they’re not kept clean the units can stop providing cool air at all.

Along with these measures to reduce their cooling needs and maximise the energy efficiency of the air conditioners, the family has undertaken a range of other retrofits and upgrades to reduce their energy consumption and be more sustainable. They installed a 4.6 kW solar PV system; upgraded the 1.2 kW single-speed pool pump with a high efficiency multi-speed one which runs on a low setting (430 W); and after identifying their 2-star clothes dryer as one of their biggest electricity consumers, swapped it for an efficient 7-star heat pump model. Chris reports that they generate 22 kWh to 25 kWh of electricity a day year round; in the dry season they use 18 kWh to 20 kWh per day, with big loads coming from the pool pump (approx 4 kWh), washing machine and dryer to handle their son’s cloth nappies (up to 7 kWh), and fans (3 kWh). In the wet, because of increased clothes dryer and air conditioner use, their consumption can be up to 30 kWh on a hot, sticky day.kWh

“We also installed energy and water monitoring systems to keep track of electricity production and consumption and water use, to help us deliberately change our patterns of use and thus reduce our environmental footprint,” says Chris.

Punkah fans for a gentle breeze

Architects Tim Bennetton and Gabriel Poole designed slow-moving ‘punkah’ fans for an off-grid house in Queensland. The result is stylish and effective.

Originally made of cloth and manually operated by pulling ropes, punkah fans have a long history in the Arab world and more recently were popular in colonial India—the name is a Hindustani word. Architect Gabriel Poole remembers admiring a set in a Port Douglas restaurant in the 1980s: “They looked great, and gave good airflow over the whole room.”

When their client Lori gave them a brief for “playful, fun” features in her house on South Stradbroke Island, not far from Brisbane, Gabriel and his colleague Tim Bennetton decided to get creative with the active cooling systems in the air conditioning free house. They collaborated with metal fabricator Barry Hamlet to design and custom-build a modern take on punkah fans. “Commercial versions of this type of fan are available, but are often not that attractive,” says Gabriel.

Installed in the open-plan living space in two rows, the system’s rigid blades are made from laser-cut curved aluminium struts covered in thin laminate sheet; to reduce waste, the blades are 2400 mm long, dictated by the size of a laminate sheet.

Each row of blades is operated by a 750 W (maximum draw) three-phase motor linked to a 750 W variable-speed drive, and is controlled by a switch similar to a ceiling fan’s. They haven’t measured the energy used at this stage. [Because of the way punkah fans work, constantly changing direction and overcoming inertia of the blades, they will use more energy than a few well-placed rotary ceiling fans, but in some situations they may be a good solution if rotary fans are unsuitable—Ed].

Homeowner Lori likes the look of the punkahs and says they provide a pleasant, gentle breeze that works well in moderate humidity. “I only run them in summer, and only when I’m actually in the room, as I’ve got the power consumption to consider,” she says; the weekender is off-grid and relies on solar, and she likes to avoid running the backup generator.

Further reading

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

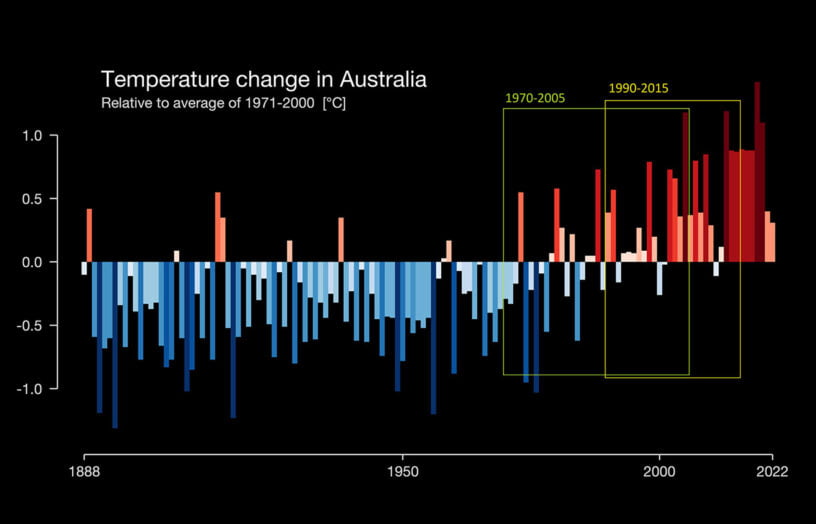

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Getting off gas FAQs

Do heat pumps work well in Australian conditions? Rachel Goldlust explains.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Air conditioner vs hydronic heating

Heat pumps can provide air conditioning or hydronic heating. But which is more efficient, and which more comfortable? Cameron Munro tells us what he learned by trying both in his super-insulated home.

Read more