Changing the world: Disruptive innovations

With the need for action on climate change getting ever more urgent, Samuel Alexander considers just how far community action can go to help build a more sustainable future.

This article was first published in Issue 129 (October-December 2014) of ReNew magazine.

It is becoming increasingly clear that small, incremental changes to the way humans use and produce energy are unlikely to catalyse a transformation to a low-carbon civilisation, at least not within the ever-tightening timeframe urged by the world’s climate scientists.

In September 2013, the IPCC published its fifth report, in which it was estimated that the world’s ‘carbon budget’—that is, the maximum carbon emissions available if the world is to have a good chance of keeping global warming below 2 degrees (a target internationally agreed to in the Copenhagen Accord of 2009)—is likely to be entirely used up within 15 to 25 years, based on current trends. If ‘business as usual’ continues, the trends indicate that we may be facing a future that is 4 degrees hotter, or more. It is not clear to what extent civilisation is compatible with such a climate.

This calls for an urgent and committed re-evaluation of the dominant strategies for transitioning beyond fossil fuels. If there is any hope for rapid decarbonisation, it surely lies, at this late stage, in movements, innovations, or technologies that do not seek to produce change through a smooth series of increments, but through an ability to somehow ‘disrupt’ the status quo and fundamentally redirect the world’s trajectory toward a low-carbon future. This article aims, then, to review several such contenders.

Admittedly, it is a difficult challenge attempting to choose movements or innovations with genuinely disruptive potential. An element of arbitrariness is inevitable, especially as there are no criteria as such by which they can be objectively ranked.

Further, the ‘tipping points’ of influential social movements in history have generally come as a surprise to the societies that they came to influence, due to the impossibility of anticipating the confluence of events and social conditions which were needed for them to flourish. Who anticipated the civil rights activist Rosa Parks? Who could have foreseen that a simple act, such as not giving up one’s seat on the bus, would give such momentum to the Civil Rights Movement?

This calls for a healthy dose of humility in undertaking the current task. As the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein once remarked about attempts to foresee the future:

When we think about the future of the world, we always have in mind its being at the place where it would be if it continued to move as we see it moving now. We do not realise that it moves not in a straight line, but in a curve, and that its direction constantly changes.

Bearing this message of caution and hope in mind, the following pages consider four social movements or social innovations that at least have the potential to change the current trajectory of history acutely in the direction of a low-carbon world.

Are the socio-cultural conditions for rapid transformation almost here? While it remains difficult to be confident, this review suggests that there are genuine grounds for hope.

1. Fossil fuel divestment campaign

This movement was initiated late in 2012 by climate activist Bill McKibben and his team at 350.org. In the 18 months since then, this campaign has taken on a life of its own, as nascent social movements tend to do.

The disruptive potential of this campaign lies in how directly it challenges the financial foundations of the fossil fuel industry—without finance the industry cannot support itself or develop new projects.

Motivated by this possibility, McKibben and his team organised a divestment campaign, which calls on individuals, communities, institutions and governments to withdraw or ‘divest’ their financial support from the fossil fuel industry with the ultimate aim of crippling it. Without investment, the fossil fuel industry cannot exist; without the fossil fuel industry, the primary cause of climate change is eliminated.

The campaign appears to be gaining momentum. In the USA, 380 college campuses have committed to divestment, with successful divestment already achieved in nine universities and colleges, 22 cities and 10 religious organisations, with further campaigns under way in Canada, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Finland, India, Bangladesh, as well as Australia and New Zealand.

While the campaign encourages individuals to divest wherever possible, the main focus is on larger institutions and organisations where the real financial power lies, especially banks, superannuation schemes, universities, churches and governments. A recent report from Oxford University concludes that this is the fastest growing divestment campaign in history.

One of the most interesting and promising elements of the campaign is how it mixes financial self-interest with environmental and humanitarian ethics. The ethical side of it is obvious enough: fossil fuel emissions are the primary cause of climate change (IPCC, 2013), thus a moral case can easily be made that people and institutions should not be investing in, or profiting from, an industry that is in the process of destabilising the climate with potentially devastating social and environmental consequences. This argument is perhaps particularly relevant to universities, for there is a glaring moral and intellectual contradiction in funding the salaries of climate scientists with profits that flow, in part, from investments in the fossil fuel industry.

This ethical defence is arguably grounds enough, but the fascinating thing is how the campaign entails a supplementary argument based on self-interest—perhaps this is where the real revolutionary potential of the campaign lies. McKibben argues that people or institutions concerned about their own financial assets should immediately divest from fossil fuels because there is a ‘carbon bubble’ waiting to burst.

The carbon bubble hypothesis is based on the notion of a carbon budget. It is estimated that embedded carbon in existing global fossil fuel reserves lies in the vicinity of 2795Gt, but the world’s carbon budget is only around 565Gt (Carbon Tracker Initiative, 2011). What this means is that, if the world is to stop temperatures rising above the threshold of 2 degrees, around 80% of the fossil fuels already discovered simply cannot be burned and must remain in the ground.

A carbon bubble exists, therefore, because currently fossil fuel shares are priced on the assumption that all reserves will be produced. It follows that any serious response to climate change is going to burst the carbon bubble by turning a vast amount of fossil fuel reserves into ‘stranded assets’ of little or no value.

The underlying threat of this approach arises out of the understanding that markets are notoriously whimsical, in the sense that they sometimes crash not because they necessarily have a reason to crash, but because a certain number of people think that they might crash, leading to divestment. Aware of this tendency, McKibben’s divestment campaign is trying to shatter investor confidence in the fossil fuel industry and spark the initial capital flight, in the hope of opening the floodgates.

Even if the campaign does not manage to bankrupt the industry economically, the campaign may nevertheless advance a critically important goal of stigmatising the fossil fuel industry as a primary enemy of climate stabilisation, thereby bankrupting it politically and socially. Historically, stigmatisation has been an important function of divestment campaigns.

While it could be argued that the campaign puts too much faith in market mechanisms as a means of responding to climate change, this potential indictment can easily be reconceived as a defence: divestment uses the existing mechanisms of capitalism to undermine what is arguably capitalism’s defining industry. The divestment campaign just might be the industry’s Achilles’ heel.

Of course, it is not enough merely to divest from the fossil fuel industry; it is equally important to reinvest in a clean energy economy. This additional reinvestment strategy provides further grounds for thinking that the divestment campaign could be of transformative significance in bringing about a post-carbon or low-carbon world.

2. Transition Towns

If the fossil fuel divestment campaign is one of the most promising social movements opposing and undermining the carbon-based society, the Transition Towns movement is arguably one of the most promising and coherent social movements focused on building an alternative society.

This movement burst onto the scene in Ireland in 2005, and already there are more than 1000 Transition Towns around the world, in more than 40 countries, including Australia. The movement runs counter to the dominant narrative of globalisation, and instead offers a positive, highly localised vision of a low-carbon future, as well as an evolving roadmap for getting there through grassroots activism.

The rationale for engaging in grassroots activity is that “if we wait for governments, it’ll be too little, too late. If we act as individuals, it’ll be too little. But if we act as communities, it might just be enough, just in time” (Hopkins, 2013: 45).

According to some commentators, this approach represents a pragmatic turn insofar as it focuses on doing sustainability here and now. In other words, it is a form of DIY politics, one that does not involve waiting for governments to provide solutions, but rather depends upon an actively engaged citizenry.

This approach is particularly relevant here in Australia, where the government is showing no signs of progressing the nation toward a low-carbon future. Of course, whether grassroots movements for a low-carbon world ultimately march under the banner of ‘transition’ is of little importance; what is necessary and important is that people do not wait for governments to act or lead the way.

The paradigm shift of Transition is articulated around notions of decarbonisation and relocalisation of the economy. What this means in practice is complex, but the overarching idea is that decarbonisation is necessary and desirable for reasons of peak oil and climate change. And, given how carbon-intensive global trade is, decarbonisation implies relocalising economic processes. As well as this, another central goal of the movement is to build community resilience, a term which can be broadly defined as the capacity of a community to withstand shocks and the ability to adapt after disturbances.

Notably, crisis in the current system is presented not as a cause for despair but as a transformational opportunity, a change for the better that should be embraced rather than feared.

Rob Hopkins, co-founder and by far the most prominent spokesperson for the movement, plays a crucial role in promoting such an optimistic message, while at the same time acknowledging the extent of the global problems and asserting that there is no guarantee of success. Whether his positivity is justifiable is an open question—some argue that it is not (e.g. Smith and Positano in The Self-destructive Affluence of the First World)— but it is nevertheless proving to be a means of inspiring and mobilising communities in ways that ‘doomsayers’ are unlikely to ever realise.

Some critics argue that the movement suffers, just as the broader environmental movement arguably suffers, from the inability to expand much beyond the usual middle-class, generally well-educated participants, who have the time, security and privilege to engage in social and environmental activism. While the Transition Movement is ostensibly inclusive, this self-image requires examination in order to assess whether it is as inclusive and as diverse as it claims to be, and what this might mean for the movement’s prospects. Can it ‘scale up’ sufficiently?

There is also the issue of whether a grassroots, community-led movement can change the macro-economic and political structures of global capitalism ‘from below’ through relocalisation strategies, or whether the movement may need to engage in more conventional ‘top down’ political activity if it is to have any chance of achieving its ambitious goals (see, e.g., Sarkar’s EcoSocialism or EcoCapitalism, 1999).

Other critics argue that the movement is insufficiently radical in its vision. Does it need to engage more critically with the broader paradigm of capitalism, its growth imperative, and social norms and values that constrict the imagination? Is building local resilience within the existing system an adequate strategy? And does the movement recognise that decarbonisation almost certainly means giving up many aspects of affluent, consumer lifestyles?

This is not the forum to offer answers to these probing questions, but engaging critically with these issues could advance the debate around a movement that may indeed hold some of the keys to transitioning to a just and sustainable, low-carbon world.

It may be that the practical reality of the Transition Movement has been over-hyped to some extent, but what seems clear is that a low-carbon world will never emerge unless there is an engaged citizenry that speaks up and gets active. Currently, the Transition Movement is the most promising example of such a social movement, mobilising communities for a world beyond fossil fuels, and meeting with some success.

A Transition Town in practice

Kate Leslie from Transition Hobsons Bay:

Based in Melbourne’s south-west suburbs, Transition Hobsons Bay started in 2010. Our activities weave a web of community connections and help to build more resilient and sustainable neighbourhoods. We have started monthly fruit and vegie swaps in Newport, Williamstown and Altona. We celebrate the equinoxes and winter solstice with shared meals. Among our other activities in 2014 are Eco and Social Entrepreneurs workshop (won an award from Sustainable Living Festival), creating art about our waterways culminating in an exhibition, free herbal teas at a bushdance (fresh herbs from local gardens), reskilling workshops (bike maintenance for kids, sourdough bread and passata) and bulk buys of eco toilet paper. A focus in the next months will be upcycling and recycling. Of course, we have a strong online presence too, with a particularly strong facebook group. We have lots of fun and show ourselves and others that meeting our needs locally needn’t cost the earth.

3. Collaborative consumption

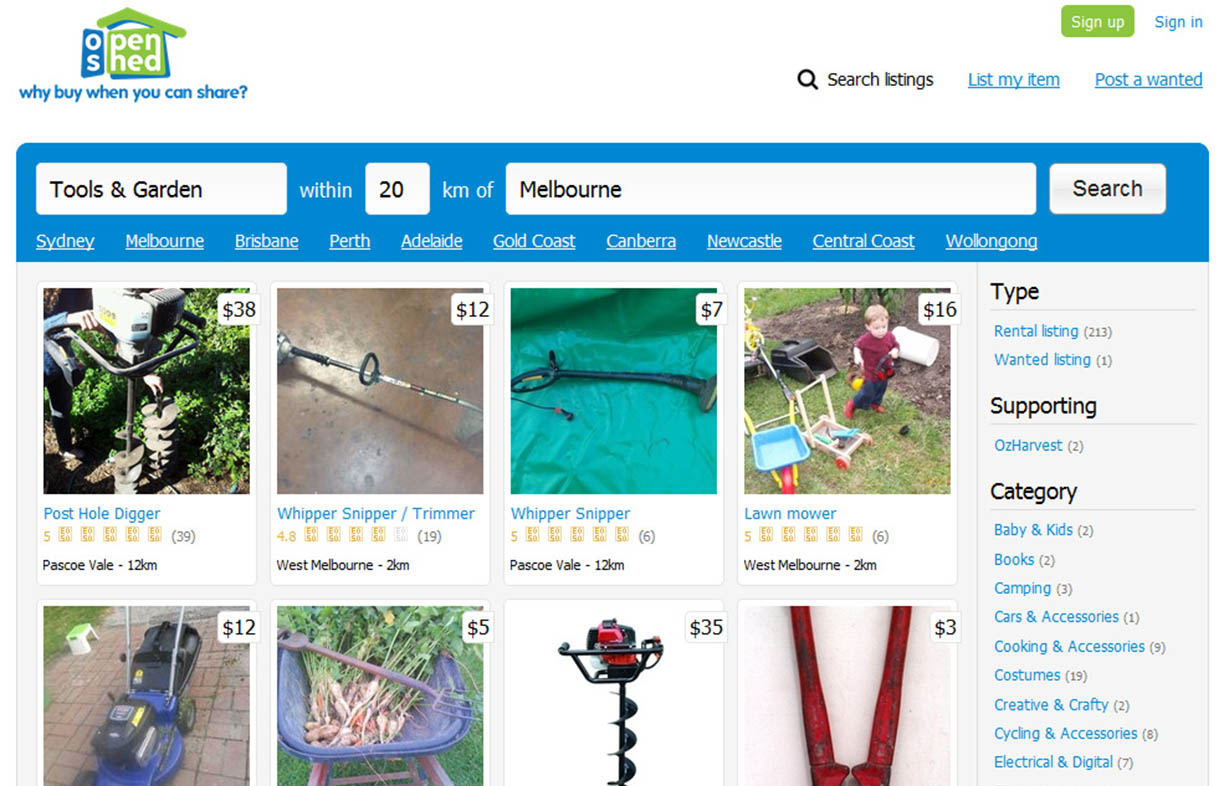

The term ‘collaborative consumption’ has emerged as one of the socio-economic buzzwords of recent times, with Time magazine in 2011 listing it as one of the big ideas that will change the world. Surprisingly, perhaps, collaborative consumption is in many ways just a fancy name for ‘sharing’, although as the prime website (www.collaborativeconsumption.com) dedicated to this concept notes, it is “sharing reinvented through technology”.

But if human beings have been sharing their wealth, possessions and skills (to varying extents) throughout history, what role could collaborative consumption play in the transition to a low-carbon world? And to what extent could something as mundane-sounding as sharing have disruptive potential?

The innovation here is that people are using online forums and technologies to offer or acquire access to things without necessarily buying or selling them; instead, they often share, hire or gift them in more or less informal ways—facilitated by online peer communities which make it easy to list or search for available goods and services. In economic parlance, the transaction costs of sharing or trading are markedly reduced through the use of the internet, making it more efficient than ever to connect formal or informal sharers and traders.

Examples of collaborative consumption are many, varied and expanding. A representative example is the upsurge in car-sharing businesses, which involve either a central business purchasing limited cars that are then used by a community of people (e.g. Zipcar, Flexicar and GoGet), or alternatively, the central business can facilitate peer-to-peer car sharing (e.g. Car-Next-Door). The genius here was in recognising that many, if not most, cars sit idle for a huge portion of the day or week, opening up space to utilise them more efficiently through sharing access.

For the same reason, bike hire has also taken off in various cities around the world, often facilitated by local or national governments. Organisations like Lyft facilitate ride-sharing, which portends a behavioural shift of paramount importance.

There are also many websites that facilitate sharing with or without monetary exchanges, such as the Sharetribe, Streetbank or Open Shed, which also function to make better use of existing resources. For example, not everyone on the street needs a lawnmower or a jigsaw (since they tend to sit idle), so sharing minimises the need for superfluous production and consumption. Other websites, such as Freecycle, rather than facilitating sharing or trading, simply facilitate the gifting of unwanted or superfluous things, thereby reducing the flow of waste to landfill.

One of the real success stories of collaborative consumption has been Air BnB, which allows people to list a room in their home as short- or long-term accommodation for travellers, providing people with an alternative to hotels and backpacker accommodation.

Botsman and Rogers in What’s Mine Is Yours (2011) argue that this ‘new’ form of consumption behaviour and entrepreneurship has the ability to radically transform business, cultures of consumption and the environmental movement. This transformative potential remains even when an exchange of money is involved, as is the case with websites such as Craigslist, eBay and Gumtree. These types of websites still provide an efficient means of reallocating goods and services beneath the surface of the traditional economy, even if these forms of exchange cannot be called sharing.

It is difficult to deny the potential of these types of collaborative exchange to challenge dominant cultures of wasteful and excessive consumption. Especially in affluent societies, where a vast amount of goods lie idle and unused, there seems to be huge potential for avoiding further production of goods (thereby reducing carbon emissions) by facilitating the efficient reallocation of existing goods through sharing, barter and trade. They also seem to have the added benefit of promoting community interaction at the nexus of social and economic life. Of course, there is the further incentive of self-interest: many people are drawn to collaborative consumption for the obvious reason that it can save money and hassle, or even make money.

Nevertheless, this potentially disruptive innovation has various risks that ought to be borne in mind too. For example, one of the obvious benefits for individuals who consume collaboratively is reduced costs; with less need to purchase a commodity, money is saved by hiring or borrowing only when needed. But this gives rise to a risk of a rebound effect—the possibility that the funds saved may be used to purchase other things, potentially negating the environmental benefits of collaborative consumption.

Similarly, by providing cheaper access to goods and services, collaborative consumption could actually increase consumption. For example, the cheap accommodation provided through Air BnB could make carbon-intensive travel more financially affordable, again negating the potential environmental benefits of sharing.

What this suggests is that, if collaborative consumption is to help catalyse the transition to a low-carbon world, these new mechanisms of exchange must be accompanied by an ethics of sufficiency, wherein collaborative consumption is used as a means of reducing the impact of one’s consumption, rather than as a means of maximising consumption. Otherwise, collaborative consumption could just as easily promote rather than undermine consumerist cultures.

4. Renewable energy financed from below

As the climate situation worsens, a louder chorus is forming amongst scientists, educators and activists that an urgent top down political response is needed to facilitate a rapid transition away from fossil fuels toward an economy based on renewables.

Lester Brown in World on the Edge (2011), among others, uses the metaphor of “war time mobilisation” to signify the urgency needed. The US economy changed almost overnight with the bombing of Pearl Harbour in 1942, responding to an urgent security threat by reconfiguring, among other things, car factories to produce tanks, planes and ammunition.

The shrinking carbon budget suggests that a similar mobilisation is needed now, this time to confront the threat of climate change, by mass-producing solar panels, wind turbines and other renewable technologies. Nevertheless, the failures at Copenhagen and later international climate-related conferences don’t provide many grounds for hope that politicians are going to be the prime movers in the transition to a low-carbon society.

However, in recent years there has been a multitude of innovations in the socio-cultural sphere that suggest that, even in the absence of serious top down political action, the transition to renewable energy supply could be driven from below.

The preeminent example is Germany, which globally produces the most solar energy per capita. The interesting point about the example of Germany is not simply how much renewable energy it is producing, but that approximately 65% of that production is owned by individuals and communities, as opposed to being funded by the public purse (although attractive subsidies exist).

Beyond Germany, there are a growing number of inspiring examples—such as the Westmill Cooperative, in the UK, and Hepburn Wind, in Victoria, Australia—where communities with less attractive subsidies have still taken the transition to renewables into their own hands.

Aiding such a transition ‘from below’, creative financing mechanisms and other innovations are being developed which have the potential to enable individuals and communities to purchase renewable energy, with or without state support. Here are some promising examples.

Crowdfunding

This refers to the collective effort of individuals and communities to pool their resources to support projects they believe in, usually facilitated and campaigned for through the internet. Small contributions from a large number of people are allowing innovators, entrepreneurs and businesses to raise capital for all types of projects, including renewable energy projects, which do not receive any or sufficient government support. Solar Mosaic, based in California, is one of the most prominent examples, with similar organisations Solar Share and Clear Sky Solar recently emerging in Canberra, Australia. Interestingly, as well as providing ethical investment opportunities, these types of organisations open up investment in renewable energy to people who may be unable to do so at the household level (e.g. due to a shaded roof or because they are living in a rental property).

Financing from suppliers

There have also been innovations in the way renewable energy can be financed, which is helping people overcome the barrier of upfront payment for renewables. As solar, especially, becomes more financially competitive with fossil energy, it is becoming economically more attractive to invest in solar panels, but some households struggle to come up with the upfront capital required to purchase the panels. That has prompted some energy companies, such as Vector in New Zealand, to offer solar panels to households with a relatively small upfront payment, supplemented by regular monthly payments for a period, rather than expecting a much larger—often prohibitively large—one-off payment upfront. Similarly, organisations like Every Rooftop offer finance to people to lease or buy solar panels with little or no upfront payments.

Environmental upgrade agreements

These agreements refer to interesting new financing arrangements between private households, banks and governments, whereby banks offer loans to households to retrofit their houses to increase energy efficiency, expand water storage or purchase solar. Instead of households paying the debt back directly to the bank, however, payments are made via local government through a rates charge. If the property is sold, the debt stays with the property, thus providing an incentive to retrofit a house, even if it might be sold in the foreseeable future. There are also means of splitting the repayments with tenants (if they consent, as they may do for self-interested reasons).

Social finance and super

Other promising developments are taking place in the sphere of social finance; that is, financial institutions that are explicitly motivated by the desire to help fund socially and environmentally beneficial projects. Australian institutions like bankmecu and Foresters are leading the way. There is also a huge sum of superannuation that private citizens around the world could access if they decided to self-manage their own super and use it to invest in renewables.

All of these innovations are taking place in the context of increasing economic (and ecological!) incentives to invest in renewables. Significant advances are taking place, year on year, with respect to the price and efficiency of solar energy, wind energy and battery storage. We can be sure that the moment renewable energy is cheaper than fossil energy, we will see a truly disruptive change within a matter of years.

Signs are emerging that this transformation could be almost upon us, if it isn’t already (see, e.g., RenewEconomy’s ‘WA grid may become first victim of “death spiral”’). Goldman Sachs has recently announced that it is investing US$40 billion in renewable investments, which it regards as one of the most compelling and attractive markets. Stuart Bernstein, who heads the bank’s clean-technology and renewables investment banking group, has recently claimed with respect to the renewable energy market: “It is a transformational moment in time.”

This article was first published in Issue 129 (October-December 2014) of Renew magazine. Issue 129 has a focus on community energy.

Community

Community

Game of life

The Adaptation Game is a new interactive board game that uses science and storytelling to simulate how you and your community can respond to the next 10 years of climate change.

Read more Reuse & recycling

Reuse & recycling

Community eco hub

Nathan Scolaro spends 15 minutes with Stuart Wilson and Michael McGarvie from the Ecological Justice Hub in Brunswick, Melbourne.

Read more DIY

DIY

Deleting the genset

If you have the need for the occasional use of a generator, then why not replace it with a much cleaner battery backup system instead? Lance Turner explains how.

Read more