What we can learn from Spain’s response to heatwaves

As Australia heads into a summer set to be marked by climate change and El Niño, resilience to extreme heat is front of mind. Renew’s Policy and Advocacy Manager Rob McLeod reports on Spanish responses to heatwaves and the lessons for Australia.

It’s not exactly news that it gets hot in southern Spain: the region of Andalucía is famous for its sunny blue skies and whitewashed walls. But there is something new about what the region is facing today.

Spain is particularly exposed to the impacts of climate change. 2023 has been confirmed as the hottest year ever recorded globally in human history, and Spain’s temperature increases are even higher than those experienced elsewhere in Europe. Projected climate scenarios suggest a serious threat of desertification across a significant part of the country.

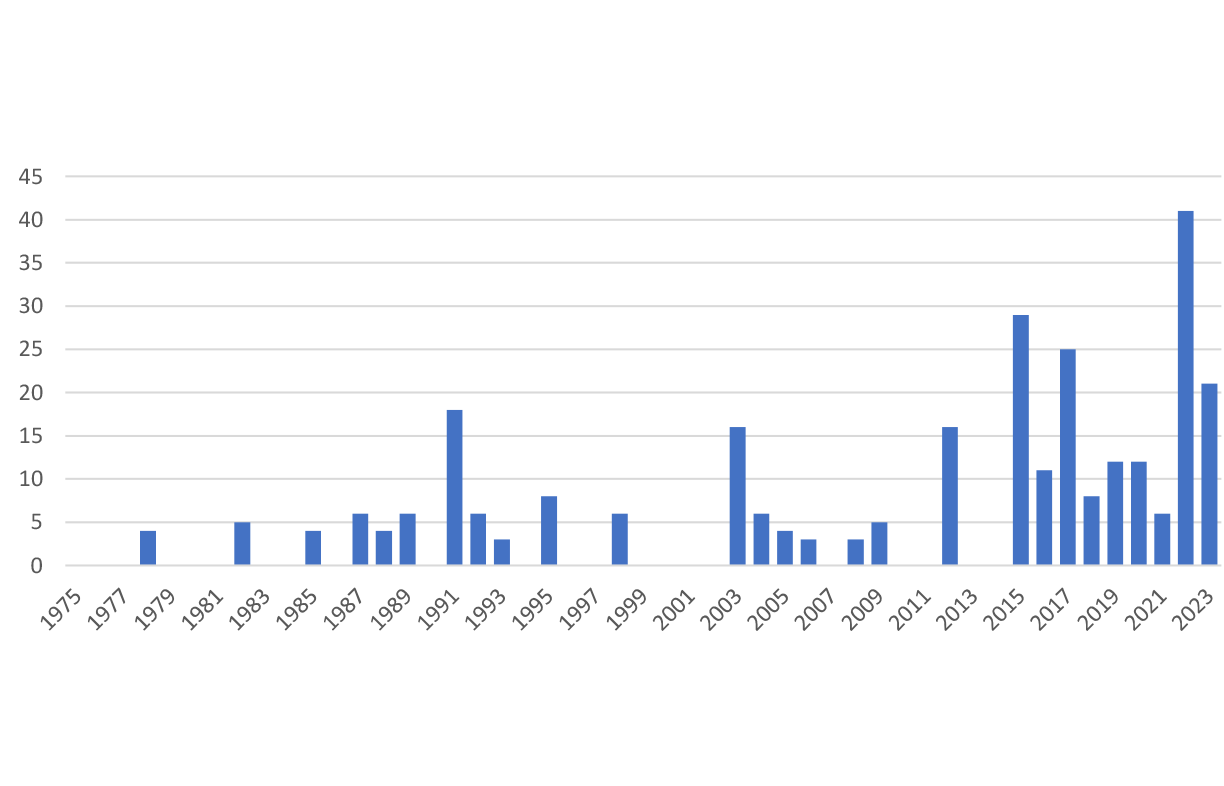

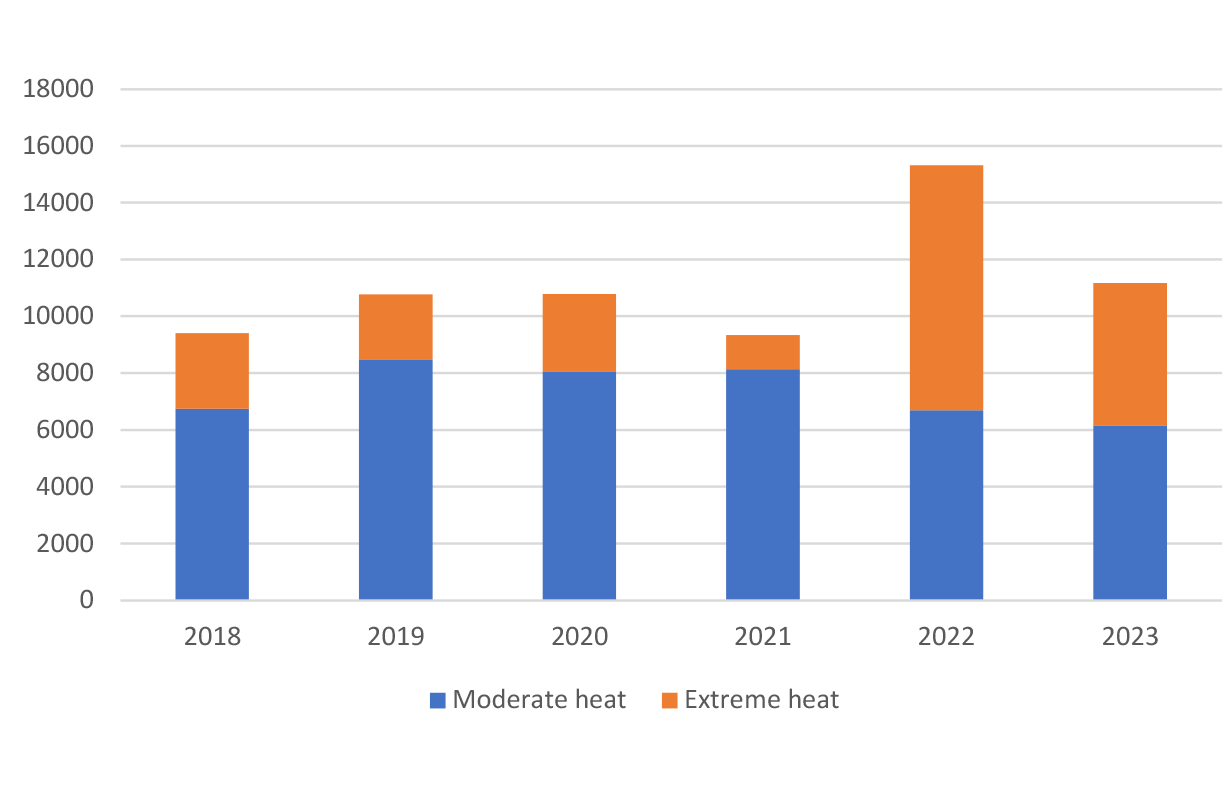

Heatwaves are increasing in severity and frequency, as well as extending further beyond peak summer months. 2022 smashed records for severe heatwave conditions, and the country again experienced four major heatwaves during the 2023 summer. One analysis finds that over 11,000 deaths can be attributed to heat over the three summer months this year.

Seville has become the first city in the world to implement a heatwave emergency naming system: in the same way Australia gives names to cyclones, Seville in 2023 has sweltered through Heatwave Yago and Heatwave Xenia. (Not all significant heat events make the cut for being named, including the record-breaking week of maximums up to 38°C in October.)

The health impacts of heatwaves pose a serious justice question. People with more resources are more likely to be able to turn on an air conditioner, work indoors or live in communities with the best access to green spaces. (Temperatures in wealthy neighbourhoods near Madrid’s central Retiro park have been recorded as much as 8°C lower than in lower-income neighbourhoods more exposed to urban heat island effects.)

The spike in deaths that accompanies heatwaves is disproportionately made up of older people—more women than men—with lower incomes or pre-existing health conditions. Cooler spaces can make a critical difference, but access to green spaces or air-conditioned free public spaces such as libraries (let alone shopping centres and businesses) is not equal for all.

A similar underlying pattern of extreme weather events exacerbating existing underlying forms of social exclusion can be found in Australia as in Spain: it is not for nothing that heatwaves have been described by sociologist Eric Klinenberg as the “silent and invisible killers of silenced and invisible people”.

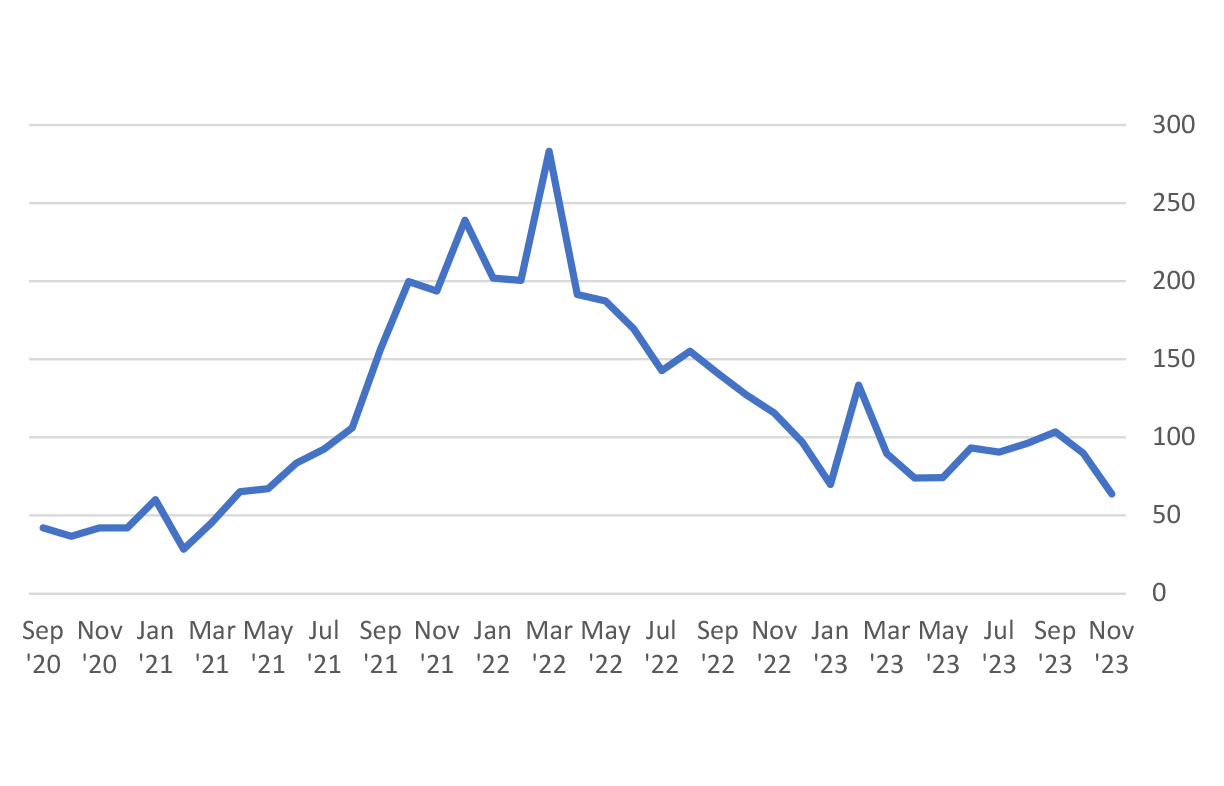

Only about a third of Spain’s homes have air conditioning, and those that do have faced rising costs. The extreme heatwaves have taken place against a backdrop of rising international gas prices in 2021 and 2022, which alongside the effects of a drought have put Spain’s energy system under significant pressure.

The energy crisis spurred a range of government responses to limit costs, including price caps, an effective temporary exit from the common European energy market, an acceleration of the transition to renewables, and demand reduction. Notably, a new law limits air conditioning use by setting 27°C as the minimum permitted thermostat setting in businesses and public buildings during summer.

The most important way to address the threat of extreme heat is by cutting emissions and mitigating climate change, but adaptation to the climate impacts that are already here is also critical. Julio Díaz, co-director of the Instituto Carlos III Reference Unit on Climate Change Health in Madrid, finds that Spanish cities are adapting to increased heat extremes: the temperature at which mortality begins to increase has been steadily rising over the past two decades.

Improved resilience may be in part attributable to natural biological acclimatisation, but also broader social and policy changes including specific adaptation measures like urban design, home retrofits, improved health systems and heatwave response strategies. However, Díaz highlights that adaptation needs to keep up with temperatures that are rising in Spanish cities by around 0.4°C per decade to avoid a significant rise in mortality. Rising temperatures mean that adaptation is like running on a treadmill that is speeding up.

The resilience agenda

Responses to heat are increasingly a focus of social mobilisation. In Seville, urban geographer Ángela Lara García highlights the emergence of social movements contesting the terms on which adaptation to heat and drought take place, such as the distribution of access to water, green spaces, pools, cool public spaces, or even electricity in the home.

The Barrios Hartos (‘Fed up neighbourhoods’) movement is campaigning for a response to repeated blackouts experienced by marginalised suburbs around Seville, including at times of peak temperatures. Community campaigns are pushing for cooling in school classrooms and extended access to public cool spaces such as libraries during peak summer heat.

City planning and urban design are critical in addressing heat island effects, as well as other factors like air pollution that exacerbate the health impacts of heatwaves. Simple and common measures include increasing tree cover and providing shading. A 2021 law required that municipalities of 50,000 or more residents implement a ‘low emissions zone’, in practice encouraging pedestrian areas and limiting vehicular traffic.

Similarly, there has been a broad trend towards greener spaces, though this has not been universal and has been subject to partisan political conflict. Controversy has followed local design decisions, for example the redevelopment of Madrid’s central Puerta del Sol square with concrete and no trees. Following local elections in 2023, a right-wing coalition government in Valencia is among those seeking to wind back low emissions zones.

As in Australia, retrofitting homes is a critical focus of resilience to extreme heat. Around 80% of Spanish homes have a low energy efficiency rating (E, F or G on the European Energy Performance Certificate scheme), leaving households exposed to summer heat as well as winter cold. Energy efficiency and electrification are clear opportunities.

A new analysis by energy not-for-profit Fundación Renovables finds that energy retrofits including heat pumps, solar where feasible, and a range of passive energy efficiency measures such as shading and thermal shell improvements can reduce energy use and emissions; installing heat pumps and addressing thermal bridging were found to be the most cost-effective measures across various Spanish climate zones.

The support available to households is instructive. The European Union-funded Recuperation, Transformation and Resilience Plan is targeting retrofits of over half a million Spanish homes by 2026 as part of a broader European ‘renovation wave’. Grants of up to €21,400 are available to cover 40-80% of the cost of retrofits, and up to 100% for socially and financially vulnerable households.

Direct funding sits alongside other regulations aimed at promoting home energy retrofits, including the mandatory disclosure of energy ratings when homes are advertised for sale or lease. With a decentralised political and administrative system, projects to support retrofits are largely taking place at the local or regional level. A prominent example is the Healthy Homes program in Getafe, south of Madrid, providing a one-stop shop for home upgrades addressing energy poverty which is available through the local council.

The challenges for renovations are somewhat different to those faced in Australia. Over 80% of homes in cities are apartments, limiting the scale of rooftop solar PV; while there is a growth in community energy models, Spain’s significant renewable energy generation is primarily in larger-scale solar and wind farms. The apartment-dominated housing stock also requires building-scale retrofits, coordination and a focus on the surrounds of buildings, sometimes resulting in challenges in addressing shared spaces or streetscapes.

Spain’s climate also means that the priorities in addressing household energy resilience differ from those in northern Europe, where energy poverty is primarily understood in terms of winter heating needs. These priorities include specific technical measures (such as the types of retrofits or shading), but also bring into view broader social dynamics.

The Cooltorise collaboration brings together researchers and organisations across southern Europe for measures addressing summer energy poverty. Miguel Núñez of Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and Cooltorise highlights the need to build buy-in for active participation as part of what is described as a heat culture, encompassing the range of practices and shared understandings that allow for greatest resilience. This includes actions within the home—using shade, choosing an appropriate time to open windows, taking possible steps prior to dependence on air conditioning—as well as shared community use of spaces around homes and public spaces broadly. Alongside facilitating retrofits and research, the program runs workshops on energy resilience, including with a focus on migrants, families with children and women-led households.

One personal reflection on speaking with people in Spain about extreme heat is that I sensed a recognition for the anxiety that so many Australians feel about our climate future. At the time of writing, Australia is looking ahead to what may be a difficult summer. While still much hotter than the historical average, the last three years have been marked by a La Niña weather pattern and have not seen a repeat of the disasters of the 2019-2020 summer. With El Niño conditions in place, this could be set to change.

Heatwaves have caused more deaths in Australia than any other natural disaster since the start of the twentieth century, but we tend to think about them less than our experiences of bushfires and droughts. There are serious lessons for us to learn about responding to extreme heat from international experiences, including Spain. This includes the technical side of adaptation, the specific steps we can take in our buildings and cities, and the best frameworks for measuring our readiness for heatwaves. But it goes beyond the technical: a reminder of what is at stake and the scale of response that we need.

This project was funded by Energy Consumers Australia Limited (www.energyconsumersaustralia.com.au) as part of its grants process for consumer advocacy projects and research projects for the benefit of consumers of electricity and gas. The views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the views of Energy Consumers Australia.

Further reading

Climate change

Climate change

Charting possibilities of the blue economy

Mia-Francesca Jones explores the opportunities of the blue economy for oceanic health, as well as human and planetary wellbeing.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy forecasts, hydrogen hype and questions of progress

Alan Pears gives us his round-up of the main energy issues this quarter.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy costs, climate impacts and quality of life

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more