Warming of 1.5 degrees: What we do now matters more than ever

We’re running out of time, and what we do now matters more than ever, was the message delivered by Professor Lesley Hughes when she spoke recently about the IPCC 1.5 report at Renew’s Illawarra branch.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s latest special report, the recently released Global Warming of 1.5 °C, makes no bones about what faces life on earth if real change doesn’t become our top priority. “I’ll just tell you right now, the news isn’t very good,” Professor Hughes said at the start of her talk at the Renew Illawarra branch in October.

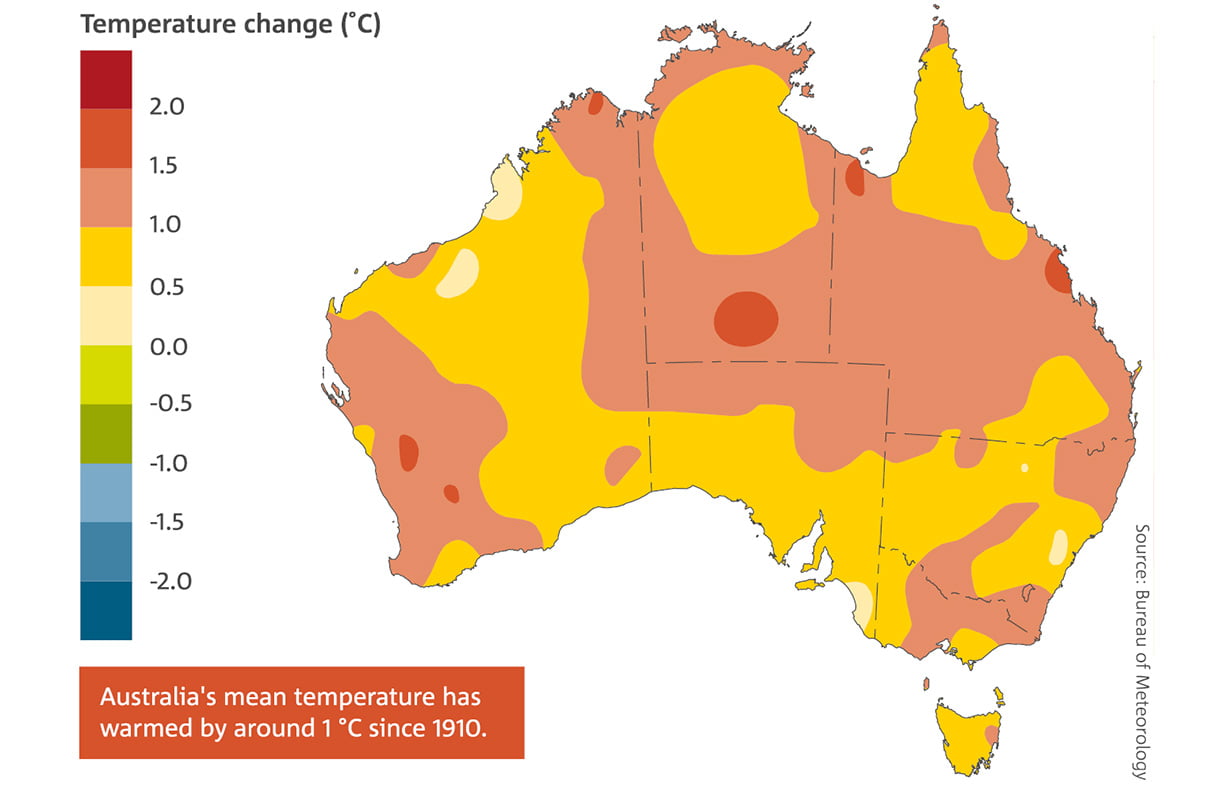

According to Professor Hughes, as at September 2017, carbon emissions in the atmosphere were at 30% more than pre-industrial levels, which equates to “about a degree of warming over the last century or so.”

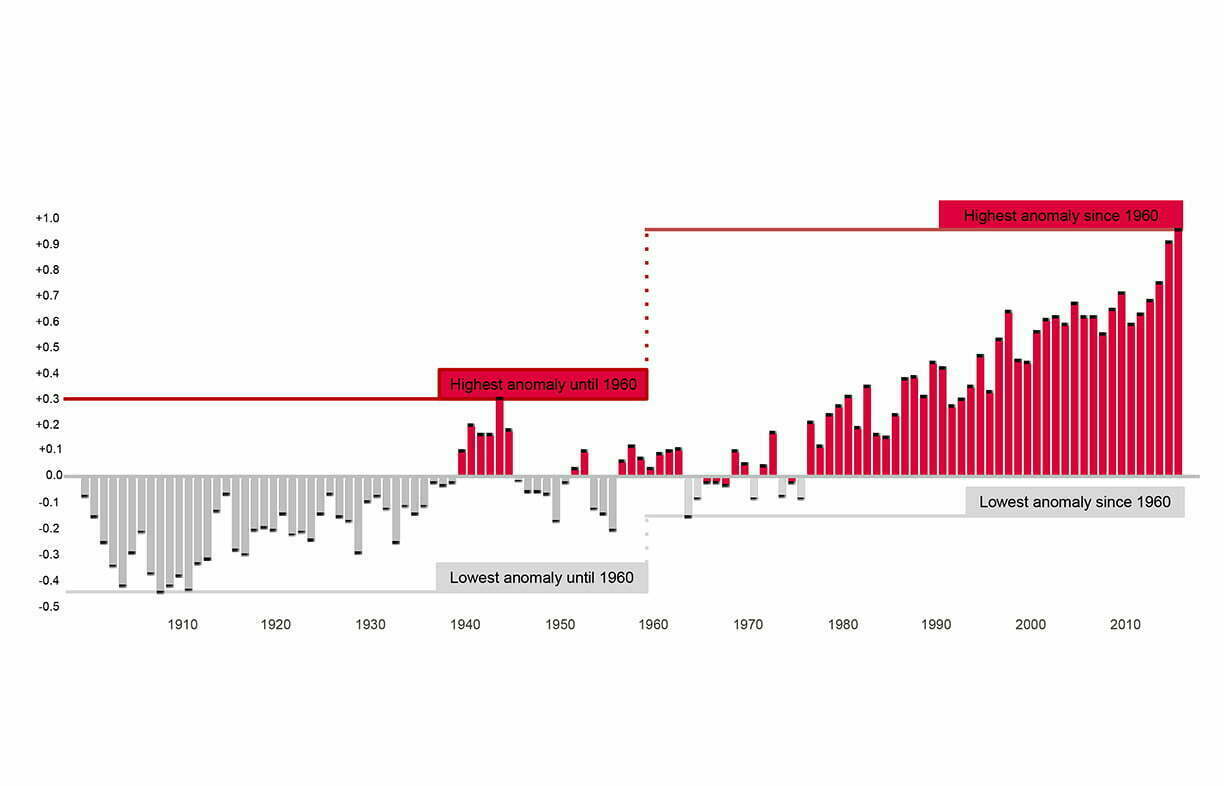

The rapidly rising temperatures during the period 1910 to 2016 are illustrated by the red bars in Figure 1. These show the difference between the mean temperature in any one year and the average temperature over the 20th century; red indicates this is greater than zero. The rise in temperature that has occurred, particularly over the last 20 years, is striking. “Since 1977 every single year has been above average,” says Professor Hughes, “and in fact, 17 of the 18 hottest years on record have been in this century.”

Climate change in Australia

The signs of climate change continue to manifest in Australia. “We’ve had double the number of record hot days compared to the 1950s,” says Professor Hughes. “Heatwaves actually kill more people in Australia than any other extreme weather event.” While 173 people died during the Black Saturday bushfires in 2009, twice that number died in the week before due to heat stress, she explains.

The Great Barrier Reef has suffered coral bleaching for two consecutive years in 2016 and 2017. And lest anyone take that as an anomaly, Professor Hughes says attribution studies conducted by the University of Melbourne indicate that the coral bleaching event in 2016 was 175 times more likely to have occurred as a result of anthropogenic climate change.

Professor Hughes noted also that:

- Australia’s bushfire seasons are far longer, hotter and more severe than in the 1970s and bushfire seasons are being declared earlier

- the water cycle is intensifying: in general, areas that are dry are getting drier and areas that are wet are getting wetter

- because the atmosphere is warmer, it is capable of holding more water, which means more extreme rainfall events when we do get rain

- plus there are multiple effects on many ecosystems.

What’s in a degree and a half?

According to Professor Hughes, previous IPCC reports have identified Australia as the developed country most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. But risks could be substantially reduced if warming is kept to less than 2 °C and, preferably, less than 1.5 °C. She notes that, globally, we have already warmed by 1 °C since pre-industrial times, so an increase to 1.5 °C is looming.

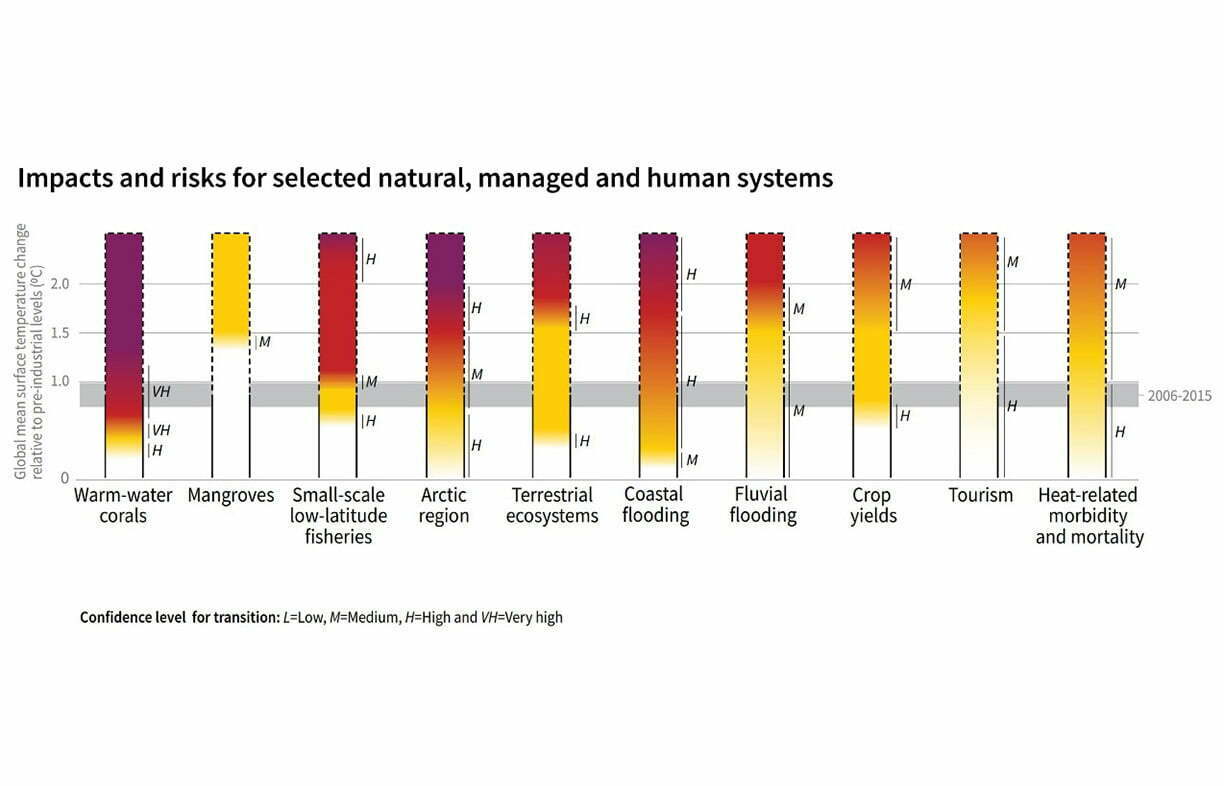

Effects of 1.5 °C and 2 °C rise since pre-industrial times are wide-reaching across many systems, as Figure 2 shows. As Professor Hughes points out, the impacts on warm water corals have been significant, even at the current 1 °C, and the impact of 2 °C will be devastating for that system.

Other systems experiencing more severe impacts at 1 °C include the Arctic region, low-latitude fisheries and coastlines that are susceptible to flooding.

Chances of keeping to 1.5 °C

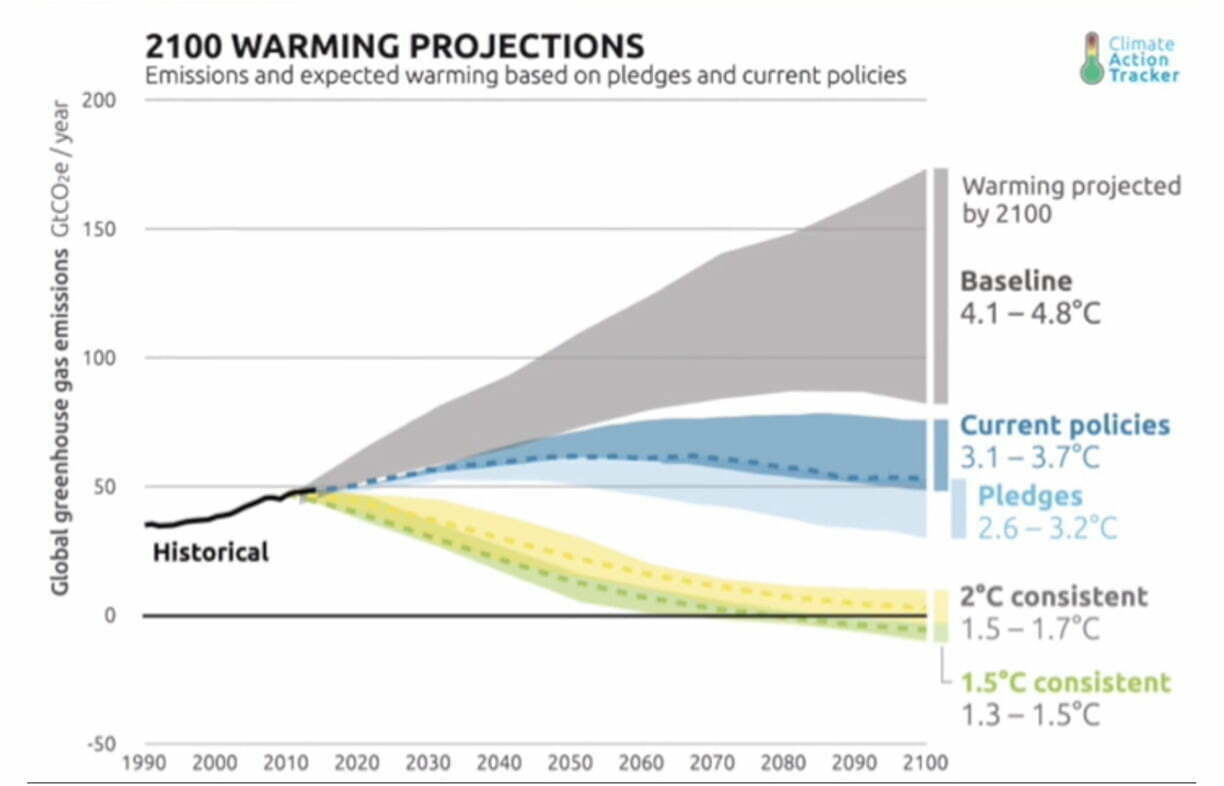

A significant question for the 1.5 °C report is: what’s the chance we can keep to 1.5? Figure 3 shows what different futures look like, based on projected warming under scenarios assessed by the IPCC.

The green band at the bottom is how much we would need to reduce emissions to be consistent with a 1.5 °C scenario. The yellow band is what we need to be consistent with a 2 °C scenario.

The blue band is what is possible given the current pledges to the Paris climate agreement—“which, as you can see, even if met 100%, still gets us to well over two degrees, probably three degrees, or possibly more,” explains Professor Hughes.

The grey band, Professor Hughes points out, is the business-as-usual trajectory, based on current emission trends.

So, while the Paris climate agreement was an incredibly important international framework, Professor Hughes says, it’s not enough. Emissions projected to 2030 under the Paris pledges, if all met, on time, will still lead to 3 °C warming.

What do we need to do?

Professor Hughes noted the tall order we have to keep under 1.5 °C, requiring, in the words of the report, “far-reaching, and historically unprecedented transformation of energy, land, urban and industrial systems in the next 20 years,” including net zero CO2 emissions by the middle of the century, for all pathways.

The IPCC report estimates that the annual global investment in energy systems—to be transformative—needs to be about 2.4 trillion US dollars. Furthermore, she says, almost all of the pathways assessed in the report require achieving some form of net negative emissions by the end of the century, and all rely on carbon dioxide removal technology.

What we do now matters

But the main message of the IPCC report is that what we do now really matters. “The longer we leave it to get serious, the bigger the mountain we have to climb,” says Professor Hughes.

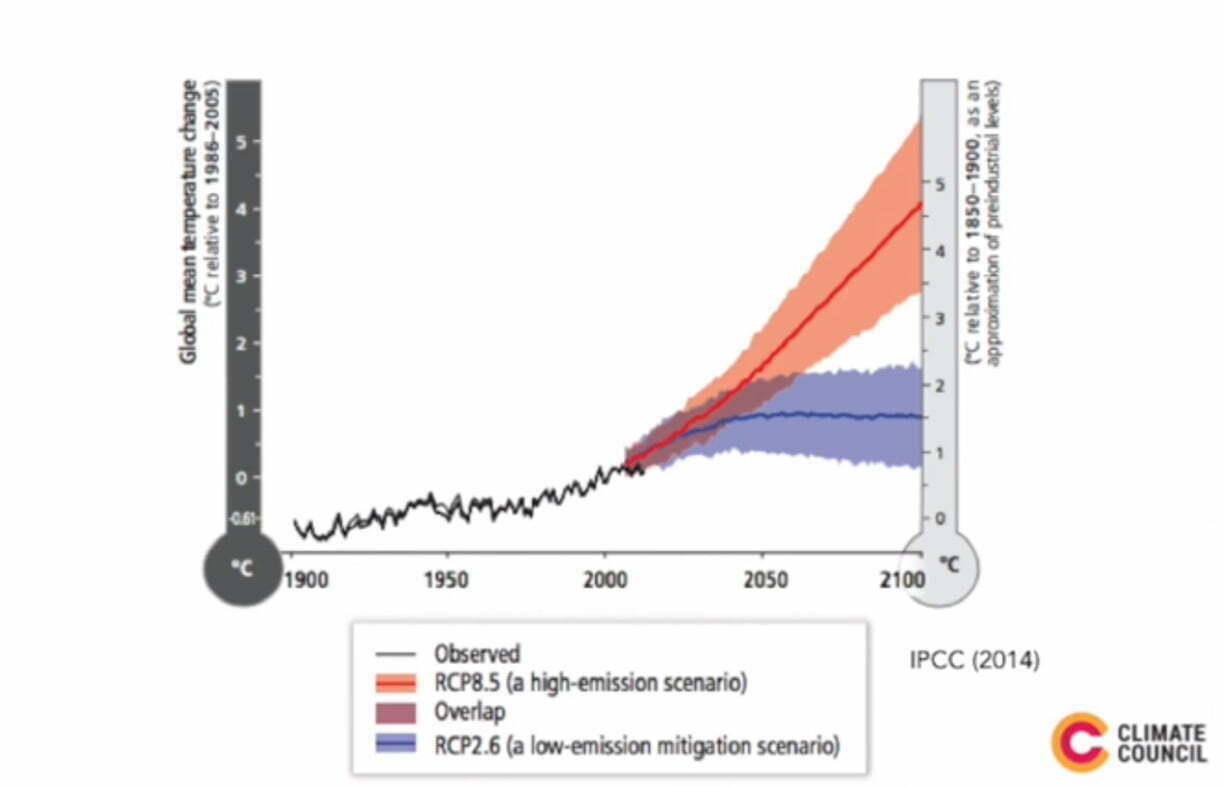

Even though the climate change that we are going to get between now and the middle of the century is pretty much locked in by the emissions that we’ve already put out there, by about the middle of the century, what we do now will begin to make a really big difference. Figure 4 illustrates this—we are in a warming scenario that overlaps for high and low emissions, but diverges significantly mid century depending on what we do now.

Avenues of change

Cities and regional centres are key to the change needed to reduce emissions. “70% of the emissions reduction that we need has to come from cities. They produce 60% of our emissions,” says Professor Hughes. She continues, “The decisions we make in the next two or three years will basically set the path for the second half of this century.”

Professor Hughes notes that change can be at the local government level. “Local councils have such an important role to play in this. There are currently 537 local councils across Australia, and where there’s a vacuum of climate policy, what you’ve got to have is the sub-national level stepping up.” The Cities Power Partnership is one way the Climate Council is supporting the power of local councils and communities working together to make change (see box).

Professor Hughes says that all the evidence is there that we won’t be able to keep under a 1.5 °C global mean temperature rise. “We do actually need to plan, at least, for two degrees, in terms of adaptation. To do otherwise would be unrealistic and irresponsible.”

In response to a question about the avenues of change, Professor Hughes believes there are many. Some of the things we need to do as quickly as we possibly can include shifting away from fossil fuels to 100% renewable energy and eating less meat. Also, we need to be managing our land and our soils to maximise carbon sequestration. We need to shift to electric transport and produce that electricity with renewables.

Professor Hughes believes there is a groundswell of support for the climate change challenge that faces us. Most surveys of attitudes in Australia in recent times have put concern about climate change at well over 70%. She thinks there’s a vast mismatch between community sentiment and current government policy.

Renewable energy scorecard

So, if, according to the IPCC 1.5 °C report, we must achieve net zero emissions by the middle of the century, how are we placed to meet this challenge here in Australia? Professor Hughes took a moment to introduce the Climate Council’s latest renewable energy scorecard for Australia’s states and territories, also released in October.

According to the scorecard, Tasmania and the ACT are “frontrunners”, with renewable energy targets of 100% by 2022 and 2020 respectively. A third frontrunner, South Australia, is highlighted as on track for 73% renewables by 2020. And, by the middle of the century, all three hope to achieve net zero emissions in the stationary energy sector.

While Victoria and Queensland both have renewable energy targets and targets for net zero emissions by 2050, they are less advanced in terms of the proportion of their energy mix from renewables. New South Wales, while indicating they are targeting net zero emissions by 2050, have not yet set a renewable energy target. Northern Territory and Western Australia have not advanced far in renewables to date and have yet to set a target for net zero emissions, though the Northern Territory does have a renewable energy target.

Despite the significant challenge in trying to respond to the IPCC report, Professor Hughes believes that Australia has fantastic opportunities. “We have brilliant solar and wind resources, we have great science, we have a stable democracy … so we have an extraordinary opportunity. If we can’t do it here, how could any other country hope to?”

Don’t give up

In parting, Professor Hughes had this to say: “People often ask me, ‘Are you optimistic?’ And I say, ‘Well, it depends on the day. But I do think that unless you have hope and optimism, you might as well just go home. Even in the most pessimistic times, you’ve got to keep trying, because that’s all we can do.”

Cities Power Partnership

A brainchild of the Climate Council’s Tim Flannery, the Cities Power Partnership is a program to support local councils in their climate action. It’s free for councils to join. When they sign up, they’re required to commit to five action pledges around renewable energy, efficiency, transport or working together to influence change. Councils are connected to exchange ideas and help each other take actions to meet their pledge. Members get free access to the Power Analytics Tool to help them understand energy, carbon and financial savings for emission reduction projects.

Further reading

Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy forecasts, hydrogen hype and questions of progress

Alan Pears gives us his round-up of the main energy issues this quarter.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Energy costs, climate impacts and quality of life

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more Pears Report

Pears Report

Fossil fuels, efficiency and TVs

Alan Pears brings us the latest news and analysis from the energy sector.

Read more