Scoring your home: Energy efficiency scorecards

Energy efficiency scorecards promise a way to compare homes and kickstart energy efficiency and liveability improvements, for both renters and homeowners. Renew’s Katy Daily looks at how the Victorian government’s Australian-first scorecard scheme could help her draughty rental home.

This article was first published in Issue 142 (Jan-Mar 2018) of Renew magazine.

Since moving from the USA to Melbourne six years ago, my family of four has been renting a tastefully restored 1926 art deco weatherboard. And, in the typical refrain you hear from almost every immigrant from a colder climate, I’ve never felt as cold as I did that first spring in Australia.

Working at Renew armed me with plenty of ideas for things I could do as a renter (and that we can take with us when we move) to make our draughty home more energy-efficient: we’ve replaced almost all the lights with LEDs, installed a Methven Kiri showerhead, added a Valvecosy to our hot water system and started insulating the hot water piping, and bought an energy-efficient refrigerator and washing machine.

We’ve done a good job of getting our electricity usage down to a respectable 4 kWh/day on average, but the house leaks like a sieve and my partner and I are both loathe to turn the heat on just to heat up the neighbourhood! As a result, our house is very uncomfortable in the winter and can be oppressive on very hot, still days and nights. We’ve been wanting to approach our landlord about draughtproofing, solar and other improvements to help make the home more comfortable while maintaining the low running costs, but didn’t know how to start the conversation.

Enter the Victorian government’s new Residential Efficiency Scorecard which rolled out in 2017. The scorecard is an Australian-first home energy rating program that gives (yet another) star rating, this time for your home, on a scale from 1 to 10, similar to the energy use star rating on a fridge or washing machine. Not to be confused with the NatHERS Star rating which describes the thermal performance of a home, the scorecard rating represents the running cost of the fixed appliances in a home (heating, cooling, lighting, hot water and pools/spas) and is intended to be used as a guide to make home improvements efficiently and cost-effectively.

In the first phase of the program, until April 2018, six selected not-for-profit organisations are deploying independent, accredited assessors to deliver free scorecard assessments for health-care and pensioner concession cardholders, those on a retailer hardship program, those who are culturally and linguistically diverse, community housing residents and renters. Anyone else can access the service for a fee. In April 2018 this will be expanded to for-profit companies who can perform the assessment and may also be able to perform the necessary improvements to raise the house’s score.

The assessor comes to your home for an on-site assessment. They use the government-supported Scorecard webtool to rate the energy efficiency of the home’s construction and fixed appliances like heaters, air conditioners, hot water systems, spas and pools, and renewable energy features such as solar PV. At the conclusion of the hour-long assessment householders receive a two-page scorecard certificate which provides an overview of the energy efficiency of the home including an overall star rating out of 10 that represents the average cost of energy for the home, the performance of key features of the home, performance of the home in hot conditions and recommendations and upgrade options to improve the home’s rating.

We were lucky to have Renew magazine contributor and occasional Renew expert Tim Forcey perform our assessment through Positive Charge. Tim explained how the assessment would proceed and what I should expect. We then toured the house; I showed him the heating and cooling systems, hot water system and pointed out what I thought were the biggest issues with the house: that all the (single-paned) windows rattled, the big gaps under our front and rear doors, gaps in the floorboards, the lack of insulation in our walls and underfloor, holes in the ductwork and absence of pelmets. We also took a look up in the attic and noted the state of the insulation, the lack of insulation around the hot water pipes and that the bathroom exhaust fan was disconnected from the exhaust duct in the roof—though according to Tim, this wasn’t hurting anything as we have a very well-vented terracotta tile roof!

Tim then took 20 to 30 minutes to measure the house and windows, research the efficiency of the fixed appliances based on age and model numbers and input the data into the Scorecard webtool; then he and I reviewed the results and discussed options for improving our score.

How did our home rate?

In a word, abysmal—2 stars out of 10! And what probably helped us achieve even that score is that we don’t have a pool or spa, and that 20% of the house isn’t actively heated or cooled so the running costs for that portion of the home are nil; otherwise, we probably would have rated 1 star.

However, there is much more to the scorecard than the star rating. It shows where we likely are using the most energy in the home—in our case 84% in heating—and that we generate nothing as we don’t have any renewable energy systems (although technically Tim would call the reverse-cycle air conditioner in our bedroom ‘renewable heat’; see Beyond Solar PV in ReNew 142). It shows that our home is “not easy” to keep cool in hot weather without using cooling. It also rated some of the home’s features against the best in class: our building shell, heating and cooling were all “very low”, our hot water was in the middle and our lighting was “very high”.

The scorecard also recommended options for improvement including upgrading insulation, adding external blinds and weatherstripping, installing double-glazed windows, more efficient heating and cooling systems, upgrading the hot water system and installing a solar PV system.

Scoring the scorecard

Like any program, the scorecard has strengths and weaknesses. In our case, our score was very low although our actual running costs ($1491 for gas and electricity over the last year) are much lower than the average Victorian home’s costs of around $3000.

For example, our score was lowered by an inefficient fixed appliance that we never use—an old window air conditioner. Had the cord been cut we would have scored higher. However, it is a fixed appliance that can be used by future occupants, so it was factored into the score.

As mentioned, our score was higher than it might otherwise have been because 20% of our home has no active heating or cooling. In fact, a co-worker’s house scored higher than ours because it has no fixed heating or cooling appliances, even though they use a portable resistive electric heater, much less efficient than a heat pump, for example. This illustrates that the scorecard rating is biased toward running costs of fixed appliances and doesn’t adequately consider actual running costs or comfort.

I also disagree with the assessment that our house is not easy to keep cool on very hot days, as we do pretty well using blinds during the day and opening windows (all of which have flyscreens) at night to allow cross-ventilation.

Danielle King, energy assessor and Renew member, summed up her feelings about the advantages of the scorecard: “while the scorecard provides a rating that enables comparison of properties, in my view the major benefit for consumers is that it provides face-to-face access to a well-qualified and knowledgeable residential energy/sustainability assessor. This is very valuable, particularly for those looking for guidance on renovating or resolving why energy bills might be high.”

The scorecard also represents an important step towards mandatory disclosure of a house’s energy performance for home buyers and renters, a key policy advocated for by the ATA to enable a shift to higher efficiency housing throughout Australia.

In our case we will use the scorecard to approach our landlord with a prioritised list of improvements to help make our home both cheaper to run and, most importantly, more comfortable to live in. With luck, our home will become as comfortable as it is beautiful—the only downside is my kids might lose their current enthusiasm to go to school in winter because the school is warmer than our house!

Residential efficiency scorecards: a brief background

Residential efficiency scorecards are not a new idea, either in Australia or internationally. In 2009, as part of the national strategy on energy efficiency, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to “phase in mandatory disclosure of residential building energy, greenhouse and water performance at the time of sale or lease, commencing with energy efficiency by May 2011.” Unfortunately, this commitment has not been met.

In the ACT, since 2004 residential properties for sale have required an energy efficiency rating, which must be made available to prospective buyers. In 2012, one of the key action points to come out of the ACT government’s new climate change strategy and action plan was to “introduce legislation to require landlords to provide information to tenants on the energy efficiency of homes and fixed appliances and major energy uses.” After extensive consultation, a pilot program was run in 2015/16 (report here). At this stage, we’re waiting with bated breath to see when and how a broader scheme will be rolled out.

The NSW government has, together with industry and research organisations, investigated the most effective way to give homeowners, buyers and tenants information about the efficiency of buildings through the EnergyFit Homes project. This research proposed a voluntary national scheme; see here for more info.

Internationally, the EU passed a directive on the energy performance of buildings in 2002 that required member states to introduce mandatory residential energy efficiency ratings schemes. In the UK, an energy performance certificate (EPC) is needed whenever a residential property is built, sold or rented, and the EPC must be made available to potential purchasers/tenants. An EPC contains information about energy use and typical energy costs, as well as recommendations about how to reduce energy use and save money. Houses for sale have required EPCs since 2007, while the requirement for rental properties was introduced in 2008.

This article was first published in Issue 142 (Jan-Mar 2018) of Renew magazine. Issue 142 focuses on energy efficiency and solar options for landlords and renters.

More on efficient homes

Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Ditching the shower fan

By fitting a lid on the shower, exhaust fans are not needed when showering. John Rogers describes this simple retrofit, using both a commercial product and a great looking DIY version.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

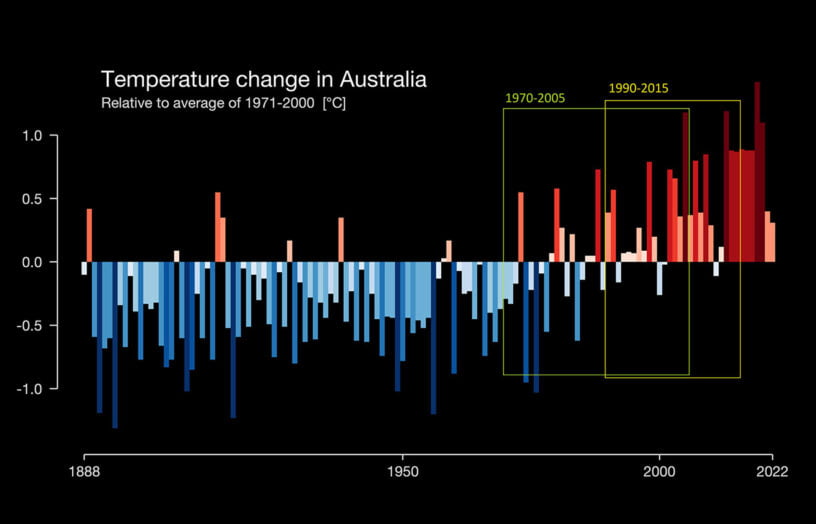

Building for a changing climate

Are we building homes for the future, or for the past? Rob McLeod investigates how climate change is impacting home energy ratings and the way we build our homes.

Read more Efficient homes

Efficient homes

Remote communities leading the charge

We learn about four sustainability and renewable energy projects in remote Australia.

Read more