Saving seed

Seed saving–the act of saving seed from vegetables, grains, herbs and flowers–has a long history. Sarah Coles speaks to Clive Blazey, founder of The Diggers Club, author of seven books on gardening and co-founder of The Safe Food Foundation about why supermarket tomatoes aren’t much chop and the reasons we should all be saving seed.

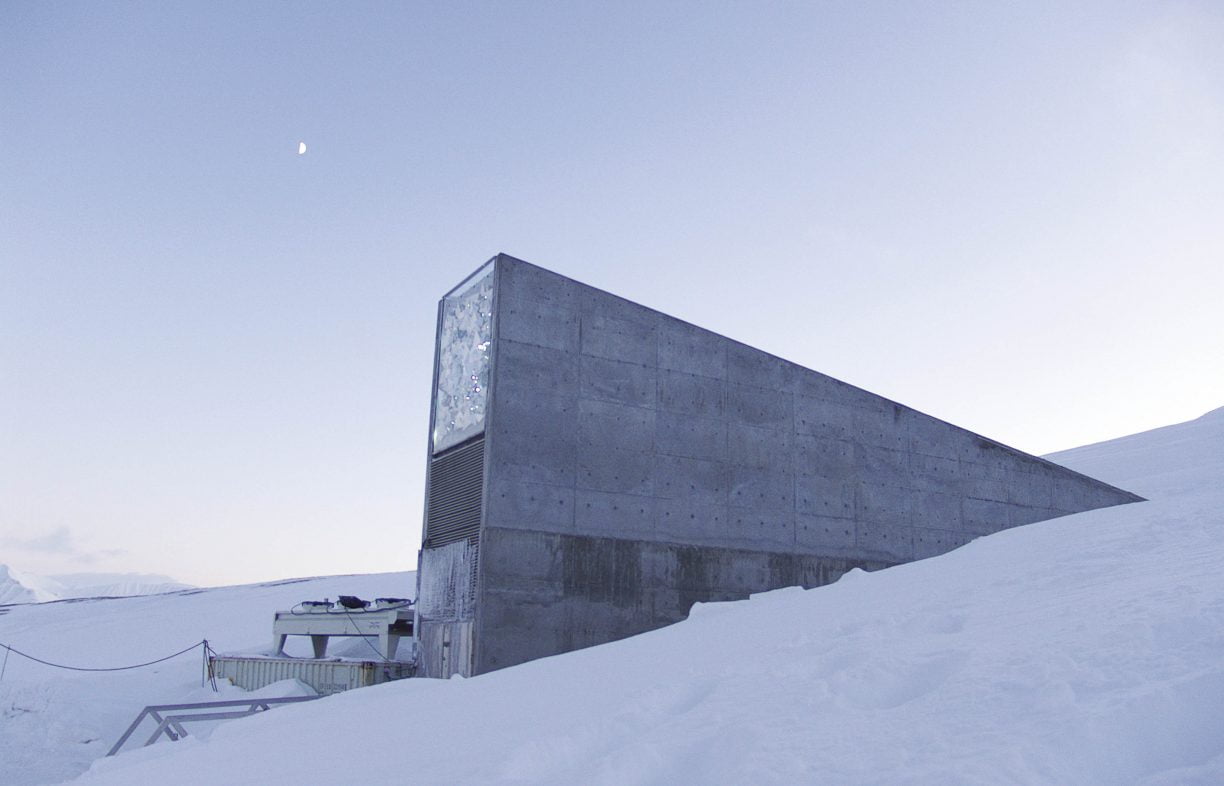

The Svalbard global seed bank, on a remote island halfway between mainland Norway and the North Pole, contains the seeds of nearly 4,000 plant species. The vault, deep in the permafrost, is designed to protect the genetic heritage of more than 860,000 seed samples from sea-level rise, earthquakes and extremes of temperature. In order for plant scientists and farmers to breed and grow food they need access to genetic diversity. The Svalbard Vault is the most diverse collection of food crop seeds in existence. During the war in Syria, scientists from the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Area (ICARDA) smuggled seed out of Aleppo in batches. Those seeds ended up in the Svalbard Vault. ICARDA have since recovered the seed from Svalbard to grow anew.

For many, seed saving is considered a life and death issue. Famously, in World War II, during the siege of Leningrad, Russian botanists hiding in the basement of the Pavlovsk Experimental seed vault starved to death rather than consume the seeds they were protecting from the German army.

Seeds you can save

Until recently, the act of saving seed or other reproductive material (for example tubers) was widely practiced. Seed saving preserves cultural identity, and promotes self-reliance and food sovereignty. Keeping seed from one year to the next saves money, and trading seed is a meaningful exchange.

There are different types of seeds. Clive from The Diggers Club explains, “Open pollinated, what we’d call heirloom seeds if they are more than 50 years old, are true to type.” True to type means that the offspring will have the same characteristics as the parent. The other type of seed is hybrid. Most seed companies concentrate on breeding hybrids, and hybrids are not suitable for seed saving because they are prone to inbreeding or are sterile. “The first hybrid seed was hybrid corn in the 1920s but it didn’t take over because in those days all farmers collected their own seed.”

Plant breeding has been practiced throughout the ages, for example potatoes, native to Peru, now grow in six continents. But over the past two decades, seed companies have introduced intellectual property rights into the mix. Farmers sign patents and licensing agreements agreeing to no longer save seed, but purchase new seed with each season. Clive is concerned about seed companies having ownership of “the life force of our food plants.” “Patents and hybrids are the same threat to our seed supply. There is some concern that by and large big companies like Monsanto that do a lot of breeding and create hybrids will be able to get access to seeds in the Vault, patent them and take over ownership.”

Clive says, “As we’re going into mono-cultures most of our biodiversity is disappearing. In terms of genetics, supermarket tomatoes are only two or three plants when there are at least 3,000 or 4,000 different types of tomatoes.” Monocultures are wide open to disease and pests. “It happened with the potato in Ireland and corn in the US,” warns Clive, “The tomato in Australian supermarkets is based on a genetic strain selected in Holland! It has a very narrow gene base.”

Saving your own seed

There’s never been a better time to save seed from your backyard. According to The Seed Saver’s Handbook, “To save good seeds you need only follow what the plants do naturally. But you do have to start with an original and viable seed stock.” This can be done by selecting plants that show desirable traits such as seeds from the most flavoursome, productive and healthy tomato bush, or select plants that exhibit good drought tolerance. If plants don’t look too flash, you can take measures to prevent them for pollinating. But remember, a healthy degree of genetic variability is important for plant health. A good way to ensure genetic variation is to plant some seeds of the original variety in with newly selected seeds.

Some people save seed to preserve heirloom traits. This is harder than saving seed for favourable traits because when you save seed to preserve genetic heritage you need to ensure your plants don’t crossbreed with neighbouring varieties or change as they adapt to local conditions. Seeds saved from plants that have been cross pollinated by other varieties do not reproduce true to type. “If you’re growing a crop in your backyard, let’s say it’s a cauliflower,and your neighbour is growing a cauliflower, if you collect the seed it will be a cross – it won’t be true to type.” Most vegetables must be kept isolated from similar varieties during flowering to avoid cross-pollination. This requires a little bit of planning at the outset.

Getting started with seed saving

Something to keep in mind is that collecting seeds from too few parent plants can damage the genetic base through inbreeding. Clive advises that the easiest plants to start with are tomatoes. “When the fruit gets soft, separate out seeds from pulp. Dry the seeds on tissue paper. Keep them cool and dry. Keep the humidity down.” Seeds need to be stored properly in a consistent, cool temperature. (High humidity can damage seeds). A good filing system and expiration dates come in handy too.

More stories you might like

Outdoors

Outdoors

Pocket forests: Urban microforests gaining ground

Often no bigger than a tennis court, microforests punch above their weight for establishing cool urban microclimates, providing wildlife habitat and focusing community connection. Mara Ripani goes exploring.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

Nourished by nature: Garden design for mental health and wellbeing

There’s plenty of evidence that connection with nature is beneficial for both mind and body. We speak to the experts about designing gardens for improved mood and wellbeing, and what we can do at home to create green spaces that give back in a therapeutic way.

Read more Outdoors

Outdoors

In the line of fire: Plant list

Download a list of popular native species to accompany our Sanctuary 51 article 'In the line of fire: Garden design to reduce the threat of bushfire'.

Read more