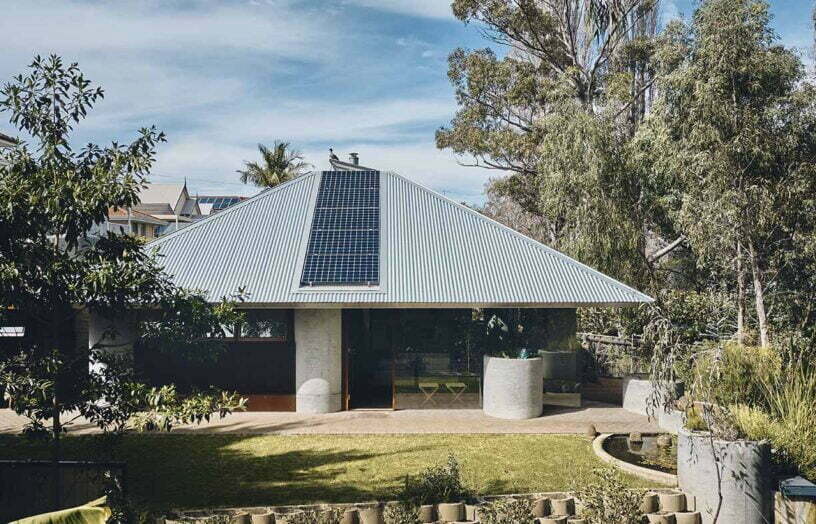

Japanese lessons

A small house doesn’t have to feel cramped, as architect James Pedersen demonstrates with this home for his growing family in Sydney’s inner west.

As an architect himself, James Pedersen is adept at finding the right balance between maximising functional spaces and keeping renovation costs down. So, when he set about extending his family home, he wanted to practise what he preaches.

James and his wife Libby purchased the one-bedroom semi-detached cottage in 2010 and since then they’ve added two children to their family. Both James and Libby work from home, so they needed more space, but only a little bit more.

Inspired by Japan’s Sukiya houses – a collection of individual ‘boxes’ that relate to surrounding gardens, rather than a box-like structure divided into rooms – James opted to add just two rooms: a master bedroom upstairs, and a verandah at the back, while upgrading the kitchen and bathroom in place. After a few years of living in the renovated house with their young daughter, James realised that the new verandah wasn’t working as he’d envisaged. In 2015, he decided to enclose the space by installing windows and doors, thereby creating a second living room that overlooks the garden.

By adding just 39 square metres to this diminutive dwelling, James created a series of flexible spaces that can be used for sleeping, working and relaxing, offering the same multi-purpose functionality that many Japanese houses provide. “I aim to integrate the requirements of people – the occupants – and place, the existing building and its environmental conditions, with as little intervention as possible,” James says.

“While it may be tempting to knock down half the house when renovating, that’s usually not the most efficient way to proceed,” he adds. “As an example, I try to keep existing structure but minimise circulation spaces, because every square metre of circulation that you can eliminate saves about $3500 in building costs. My designs combine both economic and ecological benefits.”

As both designer and owner-builder on this project, James was able to test several new architectural ideas, and he’s been pleased with the results so far. A 2000 litre water tank in the second living room adds thermal mass to that space, thanks to its northern and western outlook. In summer the tank performs as heat sink to extract heat from the room, and in winter, when the water temperature hovers around 15 degrees Celsius (or slightly higher when the sun directly hits the metal skin) it passively heats the room.

“Years ago I worked for a clever bloke who experimented with trombe walls, and he built his own house in concrete with water vats in the walls,” James recalls. “Water has better heat retention properties than sandstone or concrete, so it made sense to put our water tank to good use.”

Another resourceful idea is the space-saving spiral staircase: timber treads cantilever from a central pole to keep the ground clear beneath. “Originally I planned to put kitchen joinery underneath the treads, but when it was installed I loved the sense of space, so I left it open,” says James.

In keeping with many Japanese buildings, this home has a wonderful hand-made quality, and James credits project builders and long-time friends Matthew Adams and Wade Machuca for helping to achieve that outcome. “We made many of the fixed windows ourselves, so we minimised the materials needed by setting the glass straight into the building’s structural frame,” James says. “We also site-welded the stair, made the kitchen benches and desks upstairs, and all the outdoor shutters upstairs.

“The handmade-ness of the build was certainly an experiment,” he says. “The stairs and shutters would have been much more expensive if we’d had them manufactured off-site.” For the three months that James worked on the initial build, he paid himself a labourers’ wage, but didn’t factor in the cost of his design fees, thereby minimising the overall project cost.

So are James and his family content in this modest Japanese-inspired house in Sydney’s inner suburbs? “So far, so good,” James says. “Libby works downstairs in the new living space with a laptop, and I work upstairs at a desk. We may need a third bedroom once our second child is a bit older, but we’ll have to wait and see.

“By adding just two extra rooms, we’ve made all the difference,” he says. “The house did feel a little bit claustrophobic before, but now there’s freedom about how we use the spaces and thanks to the garden views, it doesn’t feel enclosed.”

Further reading

House profiles

House profiles

An alternative vision

This new house in Perth’s inner suburbs puts forward a fresh model of integrated sustainable living for a young family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Quiet achiever

Thick hempcrete walls contribute to the peace and warmth inside this lovely central Victorian home.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Pretty perfect pavilion

A self-contained prefabricated pod extends the living space without impacting the landscape on Mark and Julie’s NSW South Coast property.

Read more