Cradle to cradle

Thanks to the choice of materials and construction techniques, this comfortable family house in western Victoria is almost entirely recyclable.

Electronic engineer turned builder Quentin Irvine has been interested in ‘closed loop’ design principles since university, when he read the regenerative design manifesto Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the way we make things by German chemist Michael Braungart and US architect William McDonough. When the time came to build a family home on their block of land in the small western Victorian town of Beaufort, Quentin and his partner Katherine decided to go beyond the standard considerations of sustainable building – passive solar design, energy efficiency and use of eco-friendly materials – to ensure that as far as possible, the house would be recyclable at the end of its life.

“The house is made of materials that are technologically or biologically recyclable and is screwed and nailed together. Wherever glues, paints and sealants have been used, they are natural and biodegradable in all but a very few instances,” Quentin explains.

He points out that often, potentially reuseable building materials are rendered too difficult or impossible to reuse or recycle by modern construction methods. “As a builder, my jobs often involve knocking down parts of houses. I realised that because of the construction techniques used, the older houses basically are recyclable; these days it’s changed and houses are all glued together.”

Quentin took pains to stick as closely as possible to mainstream building techniques so that his design ideas would be readily replicable by the mainstream building industry. “If you look up the specifications in the National Construction Code (NCC), often there is a ‘screw’ option as well as the more standard ‘glue and nail’ option. Nothing that we did is that ‘out there’; it just involved thinking about recyclability at every tiny step of the way.”

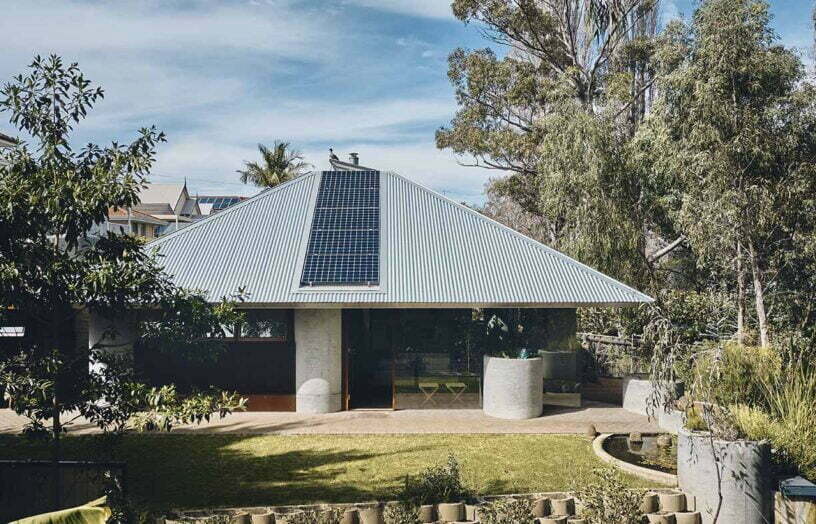

Built across the width of the block and opening to the north-facing back garden (Katherine’s pride and joy), the modest two-storey house is just one room wide to maximise cross ventilation and solar gain. “Beaufort is pretty cold for nine months of the year, so passive solar gain is a priority,” says Quentin. “The design is biased towards winter performance, with large northern double-glazed windows and doors to admit winter sun, and plenty of insulation.” This attention to passive thermal performance limits the need to use the Pyroclassic wood-fired stove which is the only heating in the house.

Timber framed, the house is constructed using a variety of new and recycled timber, much of it sourced from the local sawmill. External cladding and roofs are corrugated steel, chosen for its durability and easy recyclability. “It’s also an aesthetic homage to the iconic Australian woolshed,” explains Quentin. To break up the austerity of the facade, the northern side is clad with ‘yakisugi’ charred timber (also known as shou-sugi-ban), manufactured by Quentin’s building business Inquire Invent. This Japanese technique offers multiple benefits: fire retarding, rot resistance, carbon sequestering, recyclability, low maintenance and a product life that should easily exceed 40 years. Inside, they selected an ‘older style’ plasterboard that doesn’t contain fibreglass, which by installing it with screws instead of glue and painting it with natural paint, gives a wall lining that Quentin describes as fully compostable.

For the bathrooms, they had to think creatively about how to achieve recyclability. “Along with cabinetry, this is one of the biggest problem areas in a normal house. Most bathrooms start with chipboard or cement sheets being glued and nailed to walls and floors, followed by waterproofing membranes and tiles. At the end you have four or more different materials stuck together. It might serve for a long time as a waterproof bathroom, but the materials have all started their one-way trip to landfill.”

Instead, they used recyclable cement sheet screwed to the floor, and then built waterproof, stainless steel floor and shower trays that were also installed without glues. Floating decking boards provide the final layer in one bathroom, and pebbles and pavers in the other. “Copper and stainless steel floor trays for bathrooms are mentioned in the NCC, but as hardly anyone does it any more the skills are being lost and it’s more expensive,” Quentin admits. “But I think of it as an investment, not a sunk cost, as the material is reclaimable, it will still be worth money in the future.”

The cedar-framed windows are the one major component of the house that are not readily recyclable, and for future projects Quentin plans to research alternatives more thoroughly. Older style jointed timber frames put together without glue could be an option. He would also consider aluminium frames – although the insulative components needed to ensure such frames are thermally efficient can mean that the material is hard to recycle. “There are also some uPVC options that are very recyclable, and even use gaskets to clip in the glazing, avoiding the need for silicone.”

Despite one or two teething problems, the couple has succeeded in their mission to build a comfortable ‘closed loop’ family home. “We basically built a house that is a whole lot of firewood, reuseable timber and useful materials for a future generation. In the meantime, it’s a lovely little place to live in.”

Recommended for you

House profiles

House profiles

An alternative vision

This new house in Perth’s inner suburbs puts forward a fresh model of integrated sustainable living for a young family.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Quiet achiever

Thick hempcrete walls contribute to the peace and warmth inside this lovely central Victorian home.

Read more House profiles

House profiles

Pretty perfect pavilion

A self-contained prefabricated pod extends the living space without impacting the landscape on Mark and Julie’s NSW South Coast property.

Read more