Gardening for habitat

Beauty, habitat and always more to learn: there’s a lot to be said for bringing a bit of the bush into the suburbs. Sue Guymer and Bill Aitchison describe their Australian native garden in Melbourne’s east.

About 30 years ago, we decided to build a house on a block where we could establish a bush garden. We were lucky to find a one-acre block next to the Mullum Mullum Creek in Melbourne’s east, about 25 km from the CBD. This was the start of a wonderful journey for us, as we built a garden to encourage habitat and explored the beauty of Australian plants.

Dealing with the weeds (and superphosphate)

The land was part of a subdivision of an old orchard and was bare apart from an abundance of pasture grass weeds. The reserve along the creek to the north of our block was an almost impenetrable thicket of blackberry.

Another problem which we have since discovered is that we struggle to grow some plants. Members of the Proteaceae family—particularly banksias and some of the leafier grevilleas—tend to die quickly. This family has specialised proteoid roots (clusters of closely-spaced, short lateral rootlets) which are highly efficient at extracting phosphorus from Australia’s often deficient soils. As a result, they are very intolerant of high levels of phosphorus. We assume that superphosphate would have been used on the orchard and is still in the soil.

We have never liked to use poisons, but our weeds were so extensive that it was necessary to poison them; in the case of the blackberry thicket, we then covered the ground in black plastic to smother any seedlings. Since then, we’ve rarely needed to use weed poisons.

Giving back to the local environment

We built our house and started to establish the garden in 1988. We were enthusiastic but inexperienced gardeners at that stage and we were both still working full-time, so we needed a landscaper’s help. We were very lucky to find Doug Blythe who had a great passion for the indigenous plants of our area. We chose two landscapers from the White Pages, based on ads which seemed to show a genuine interest in Australian plants. It turned out that Doug was a member of our local Australian Plants Society group.

Doug provided the design and he and his workers did the shaping and planting. We left selection of the indigenous plants to Doug, but we chose the other natives. It was a great joy working with him to establish a bush garden. Doug worked in our garden for a number of years before he moved interstate. He has now retired from landscaping.

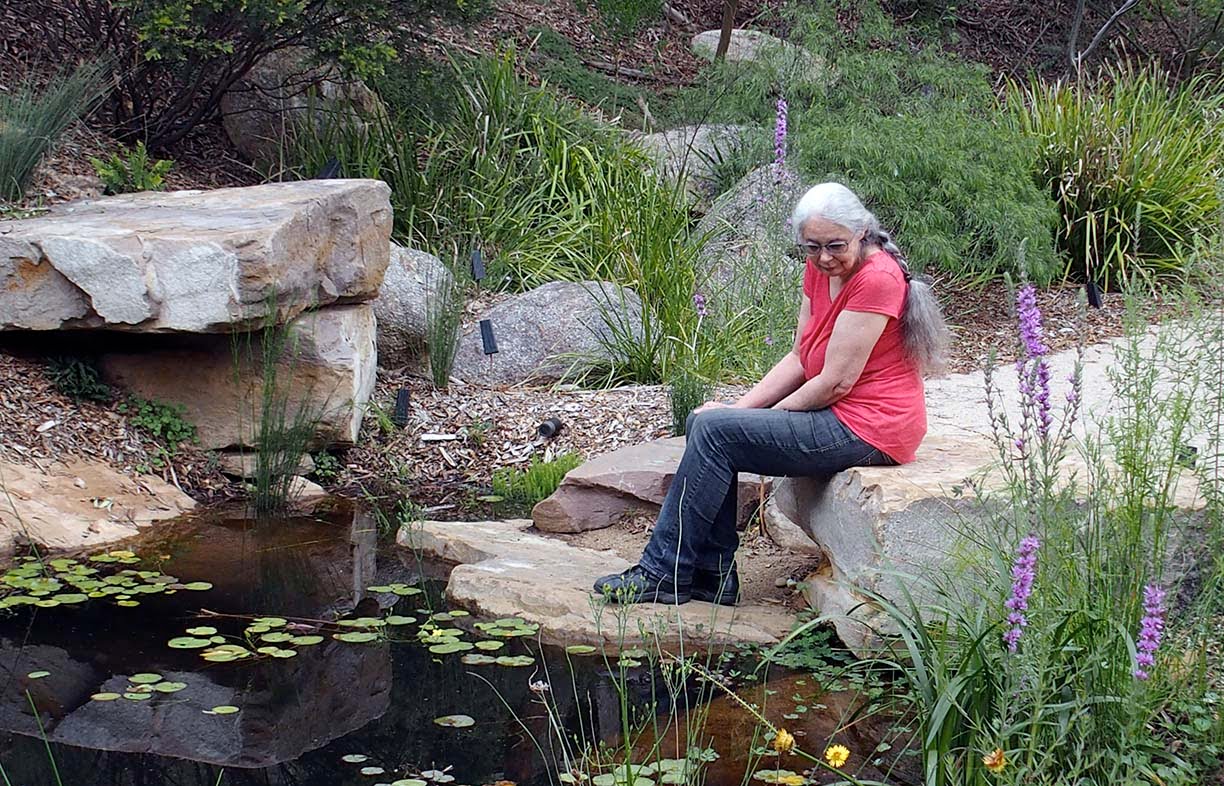

Our philosophy for the garden was to give back to the local environment, particularly extending the wildlife corridor along the creek. Doug recommended putting a lake in the bottom section of our garden, near the boundary with the creek reserve. This has proved to be a brilliant attraction for water birds as well as a beautiful feature. At the moment, we have a pair of dusky moorhens nesting on the lake.

Bushlike within 10 years

We were very lucky timing-wise. The early 1990s was a period of good rainfall and hence the plants, particularly the trees, established well. Everything had to be planted. The indigenous plants were sourced in forestry tubes from the one indigenous nursery in our area at that time, Knox Community Nursery run by the Knox Environment Society. In the early days, we focused on trees—the understorey came after these started to grow taller.

Species selection was driven by availability. We chose species which occur in our local area, but the plants we could get were sometimes sourced from other areas of eastern Melbourne, so could be slightly different forms. Trees included eucalypts (Eucalyptus viminalis, E. mellliodora, E. polyanthemos, a being the main ones) and wattles (particularly Acacia mearnsii, A. melanoxylon, A. dealbata and A. implexa). We planted Melaleuca ericifolia at the edge of the lake along with aquatic plants including Eleocharis sphacelata, water ribbons and bulrushes.

Tube stock has many advantages over larger plants. They’re cheaper and easier to plant and the plants seem to suffer less transplant shock. They establish quickly and grow rapidly. Our garden was looking ‘bushlike’ within 10 years.

The understorey has proven more difficult to establish due to dryness. This is partly due to establishing near the trees and partly because the climate was drying. Many of the very small plants succumbed. We were more successful with larger plants such as callistemons, allocasuarinas, Dodonaea viscosa, Acacia verticillata, A. paradoxa, A. acinacea, Correa reflexa and tree violets.

These days there are many more indigenous nurseries around and it is easier to find plants of relatively local provenance. We continue to put in new plants—later plantings include several species of pomaderris which we can now source through a local nursery.

We don’t have a lot of natural revegetation from our older plants, although this seems to be increasing. Einadia nutans (nodding saltbush) is spreading, and recently we have seen Dichondra repens covering over a trench which was dug when our sewerage was connected. We also redevelop areas of the garden from time to time.

A passion for Australian plants

Tempted by the amazing variety and flowering splendour of plants from further afield, particularly the many colourfully flowered Western Australian shrubs, we chose to plant some non-indigenous Australian plants close to the house—some in beds and others in pots.

We have a great passion for Australia’s native plants and have been members of the Australian Plants Society since 1987. Our local group has monthly meetings with a speaker and discussion of specimens brought in from members’ gardens, and a monthly garden visit. The state body also runs occasional weekends across Victoria and biennial seminars on a particular topic, usually a plant genus or family. There are national conferences in the intervening years; the 2019 conference was held in Albany. We have gained a considerable amount of knowledge, as well as much-valued friendships, through the wonderful people of the society. There is always someone you can ask about a particular plant or problem. For instance, one of our friends is a former nurseryman, another lives and breathes eucalypts and several are landscapers. One of the latter helps us with problems including recently fixing a broken lattice gate.

We both have our favourite plants. Bill has a particular interest in acacias; we currently have over 70 different species in the garden—and there are always new ones to try. Sue loves correas and eremophilas in particular. Correas occur naturally in southern and eastern areas of Australia so most grow well for us. Sue particularly likes the orange-flowered forms of Correa pulchella. Eremophilas come from hot, dry inland areas; some cope with Melbourne conditions but some are very difficult. Forms of Eremophila glabra and E. maculata usually do well for us and there is a great variety of foliage and flower colour, as well as height and spread of these plants. Of course, the most alluring species are often the most difficult. We are on to our third attempt at maintaining Eremophila muelleriana—difficult even with a grafted plant in a pot. (Many of the grey-leafed eremophilas resent moisture on the leaves.)

Very little maintenance

We probably don’t do as much maintenance as we should. Sue loves to weed (by hand), so our garden is relatively free of weeds. The same can’t be said for the creek reserve. We weed there from time to time, but it’s hard to do it frequently enough to make much headway. We concentrate on the strip of reserve immediately adjoining our property to try to limit weed spread from the reserve into our garden—‘defensive’ weeding. We also collect small branches which we put through a heavy-duty mulcher.

We do very little pruning in the indigenous area, mainly due to the amount of work which would be needed. However, we acknowledge that plants are ‘pruned’ in nature, by animals such as kangaroos crashing through and nibbling plants, and by fire. Closer to the house, we tip prune the plants: we pinch out the tips on soft, new growth (particularly on young plants) and use secateurs to cut thicker stems after flowering. We prune quite lightly as we want to avoid having our plants looking too shaped and formal.

…and little watering

We don’t have a watering system. Originally we had an enclosed fernery along the side of the house which had an automatic watering system, but we discontinued that when water restrictions were imposed in Melbourne. We have never turned the system back on as we can’t justify this use of water in such a dry environment. We are trying to re-establish hardier ferns and some terrestrial orchids in this area, occasionally watering manually. This ‘fernery’ has now been enclosed with cat-proof netting to provide a large cat run for our fur kids.

Other areas of the garden only get watered (by hose) when we are establishing new plants or when the plants look truly desperate. Most of our original trees are sufficiently established that they survive the drying climate. However, we do lose some—and understorey shrubs are more vulnerable to the dry.

We also have several pots of non-local Australian plants close to the house, such as some beautiful Sturt’s desert peas. These are watered on a regular basis. We collect some rainwater for this, using a number of buckets in the garden. (We don’t have water tanks as our roof water is all directed into our lake and a newer water body.)

Soil matters

We have always avoided altering our soil in the past. It is heavy, compacted clay, but we always thought it well suited to our local plants. We have occasionally used some gypsum to help break up the clay, but have been wary of bringing in new soil or significant amounts of compost, as this invariably brings in more weeds. Having said that, we do have a compost system (three bins). The purpose of composting for us is mainly to use up rubbish—food scraps, paper, cat litter (made from rice husks)—and keep it out of landfill. We apply our own compost sparingly on some of the garden beds close to the house, but not in the indigenous plant areas.

We are changing our attitude to soil treatment. In particular, we have become more aware of the importance of fungi, microbes and other soil dwellers in the health of the plants growing in the soil. We have started to use a probiotic (GoGo Juice) particularly when planting in non-indigenous areas. We chose GoGo Juice because it is organic and seems to be safe to use with native plants. It contains a mix of a wide diversity of beneficial bacteria and fungi, as well as kelp and humates. This is a recent change so we are watching for results.

Gaining, and sharing, knowledge

Our knowledge about Australian plants largely comes from the Australian Plant Society, but also from the wider Australian plant community—indigenous plant nurseries, Friends of Cranbourne Royal Botanic Gardens and our local Manningham City Council who run monthly talks on environmental subjects.

We also use a lot of books on Australian plants. In particular, Flora of Melbourne is an invaluable reference for our local plants. Books are particularly useful for finding out about a plant we don’t know—what conditions should it like, how big should it grow. We also check with friends about this information. The internet is less useful as there seems to be a lot of misinformation—for instance, in our experience, searches for photos of a particular species often turn up the wrong plant!

Habitat gardening has become more popular recently—we immediately recognised that this is what we have been trying to do for so long. There is now a lot of information about the subject. AB Bishop’s book Habitat is inspirational and has many practical tips. We have learnt that “mess is good”—we leave some areas covered in leaf litter and fallen logs. When a tree dies, we leave it in situ as these are often important bird-perching sites. We have been rewarded by noticing more and more species of animal living in or moving through our garden. We have had an echidna, a kangaroo (that jumped the fence from the creek reserve), probably over 60 bird species, reptiles, frogs and a staggering array of insects.

A couple of years ago we had the brilliant designer, Phillip Johnson, convert our swimming pool into a superb billabong system—but that’s another story.

We find our garden both relaxing and incredibly rewarding. We feel that we have achieved our aim of providing habitat for local fauna. Gardens are living, evolving systems; there is always something new to observe and we continue to learn. Hence, our garden provides intellectual satisfaction as well as physical and spiritual benefits for us.

Australian Plants Society

The Australian Plants Society forms a community for like-minded enthusiasts of growing Australian flora. Sue and Bill have been members of the Australian Plants Society Victoria (and the Maroondah district group) for over 30 years. The Victorian society’s motto is “preservation by cultivation”.

This society (which was previously known as the Society for Growing Australian Plants) has been a wonderful source of information on gardening with natives. They have introduced many Australian plants into cultivation, including many which are endangered in their natural habitat. It operates in all states and territories under various names.

There are also study groups. These are special interest groups which operate across Australia (and sometimes have members overseas). Bill is the leader of the Acacia Study Group. He produces a quarterly newsletter on all things relating to Australian acacias. There is also a seed bank run for study group members to try to help people to gain access to growing unusual or threatened species.

Further reading

Products

Products

Product profile: Pods for veggies

With the cost of food trending rapidly upwards, the move to growing food at home has become a popular one. While it’s easy if you have a garden, what do you do if you don’t?

Read more Water saving

Water saving

Nurturing your native garden

Just how much maintenance do you need in a native garden? Robyn Deed gets some tips from landscaper Haydn Barling on how to sustain a beautiful, biodiverse garden in the suburbs.

Read more