Rainwater tank case studies

Garden watering with pump and sprinklers

Lynton and Helen’s tanks were chosen as they were the biggest that would fit in the locations available. A 4500 L tank is equipped with a Davey Aquamate single-speed pump which enables watering of the vegetable garden via a sprinkler system, and hand-held hose watering of the remainder of the backyard. A 2000 L tank has a single-speed Onga SMH45 pump with a ‘waterswitch’ to switch between tank and mains water, and is connected to the cistern in the ensuite toilet and also to a tap which allows hand-held hose watering of the garden. A smaller 1000 L tank sits on a steel stand and has a tap for filling buckets and watering cans.

All three tanks are filled via 90 mm downpipes from the house’s roof gutters. The couple has not installed first-flush diverters because there was never any intention to use the harvested water for drinking, but the 2000 L tank is fitted with a filter on the tank outlet to maintain water quality for toilet flushing. Lynton says the cartridge in the filter has only needed changing once in 14 years.

Thanks to the water tanks, the household’s mains water usage is usually 80 to 100 litres per person per day, well below the state government target of 155 litres.

“The only problems we have had resulted from fine needles from a tall casuarina getting through the fixed gutter guard and clogging up gutters and downpipes,” Lynton says. “The gutter guard is bolted down at frequent intervals and it is a demanding task to remove it to clear the gutters and pipes.” They have now had the tree removed and are hopeful the problem is resolved. He adds: “A minor aesthetic problem stems from the flat tops of the tanks where water, leaves and silt collect after rain. A gently sloping conical top would have been much better.”

An off-grid water system with usage metering

In Queensland’s Currumbin Ecovillage, Rod McLeod and his family have spent considerable time and effort on their water supply system, which includes stainless steel tanks, pH-raising filter, cold water return devices, special guttering and extensive water use monitoring. Rod talks us through it.

Our 3700 m2 property is semi-rural and off the mains water grid, so we need to be self-sufficient for water. Our system consists of three 22,500 L stainless steel tanks positioned around the house to take water off the different roofs efficiently; the water is plumbed to the house, garden taps, chicken coop and garage. We also have a 5000 L firefighting tank which is filled from the overflow from one of the tanks.

The capacity of the system was selected based on the water usage of other homes in the ecovillage and on the experience of our architect, who also lives here with his young family. We made the concrete pad that the main water tank sits on large enough to take another 22,500L tank if required, as it’s cheaper to pour one large slab than two smaller ones. The system is fitted with a Reefe variable-speed pump, which reduces energy consumption as we are living off the electrical grid and rely on battery storage for overnight energy use.

Design considerations included minimising plastic components, meaning we opted for copper pipework for the tank and house, and water conservation. To this end, the kitchen and main bathroom have RedWater cold water diverters fitted to the hot taps to return back to the main water tank the water that is usually wasted before the hot arrives. We also have an Aquatrip water leak detection system. This monitors the water flow within the system; if it detects a water leak, it stops the water and alerts us to a possible fault.

The three water tanks are fitted with 10 L first-flush diverters that slowly drain to a swale. The maintenance of the diverters involves, once every couple of months, simply removing the bottom cap and hosing out the debris and filter. The gutters are a unique design from Eaves Water Systems, which does not require gutter guard. We have very few leaves caught in our first flush-diverters and therefore cleaner water and reduced tank maintenance.

We filter our water as follows:

- garden taps are not filtered or pH adjusted

- washing machine and toilets are filtered with a 25 micron washable pleated filter

- the rest of the house, including the hot water supply, is filtered and pH adjusted via a calcite filter raising the pH to about 8.5, as rainwater is quite acidic. There are two stainless steel filter canisters, the first fitted with a 5-micron sediment filter and the second with a 0.5-micron filter.

We change our filters approximately yearly. The changing or cleaning of the filters is a simple process taking about 15 minutes.

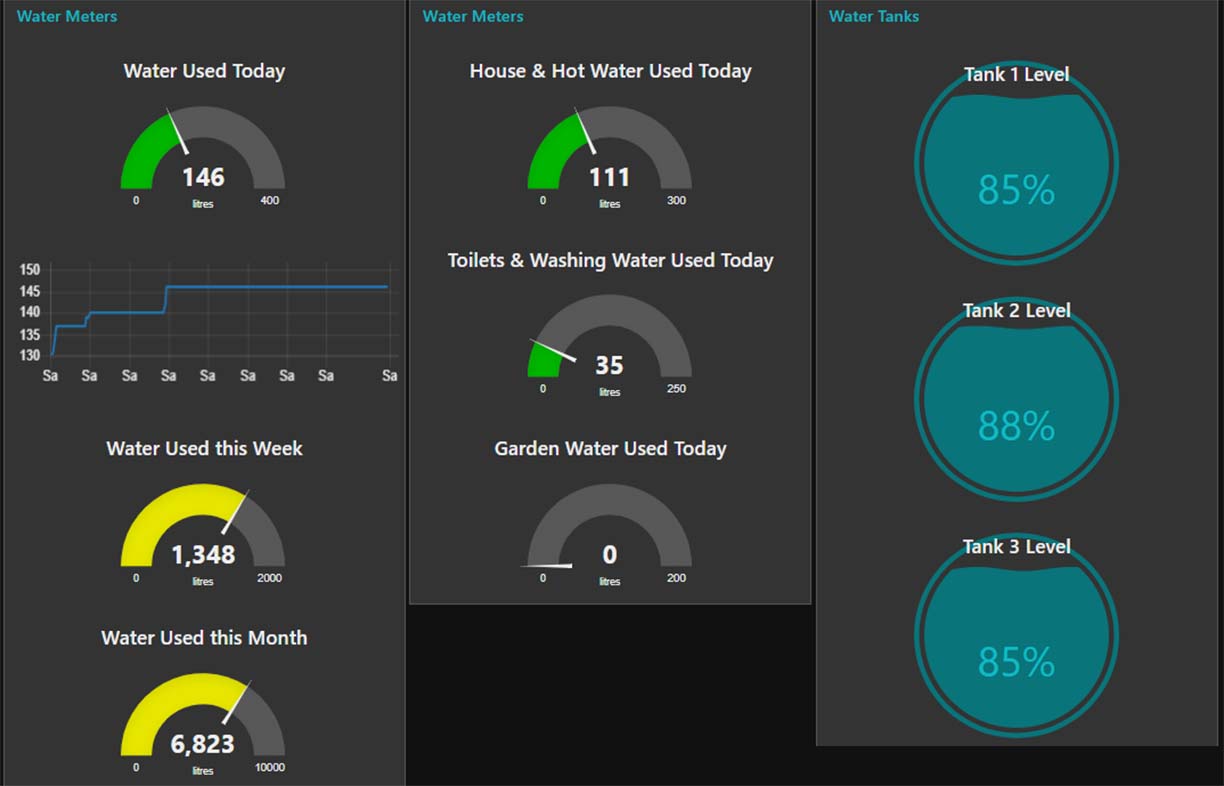

We monitor our water usage with water meters and tank-level pressure sensors connected to a controller, with the data displayed on a monitor in our kitchen to prompt us to modify our usage. There are three separate meters: for the garden, washing machine and toilets, and for the rest of the house. Monitoring the tank levels means we know when to isolate a tank from the water supply system. We have been living in our home for a year now and have not fallen below a total capacity of 70% full.

Our system is working as expected to date, and we are in a continual process of tweaking it as we gather more usage statistics.

Running (mainly) on rainwater

In rural South Australia, Lyn and Carl Gross’s rainwater harvesting system supplements a low-pressure ‘remote mains’ supply. Carl explains how it works.

We live in Caloote, a small rural village on the westernmost point of the Murray River, about 80 km out of Adelaide. The mains water supply terminates about 50 metres down the road, giving us access to ‘remote’ mains water: this low-pressure supply flows into a 3750 L mains reservoir tank from where we use a pump to give us water under pressure.

As this mains water is ‘Adelaide water’, much maligned for not being that palatable for drinking, we were keen to install as much rainwater harvesting capacity as possible, given also the paucity of rain in the area (our annual rainfall averages only about 300 mm). In a reversal of the usual setup, we use mains water to flush our toilets and water the garden, and delicious rainwater for all other uses in the house.

We have three main rainwater tanks (poly tanks from Bushman) connected to the house: two 22,500 L and one 13,600 L. The two large ones are positioned close to the house, so that the downpipes direct water straight into the tanks to avoid having a wet system. The smaller tank is fed directly from the garage roof. I also installed a narrow plastic tank (only 200 L) at the corner of the house by the kitchen to enable storage of drinking water. This tank has a downpipe emptying into it, with an overflow connected to the main tanks.

After a year or two of seeing water overflowing and being wasted when the tanks were full, I installed another 22,500 L tank on the other side of the garden shed. This is not rain-fed, but must be filled either by gravity or by pump. It functions only as a supplementary reservoir. I made a mistake with this tank, because a lower profile tank would fill completely by gravity, instead of having to use power to top it up with a pump.

We have a Grundfos CH2-30PC single-speed pressure pump. Most of the time it pumps the rainwater to the house and to three garden taps, but I can manipulate a couple of taps to swap between pumping rainwater and pumping from the mains reservoir tank when needed.

The mains water is used mainly for watering the garden, mostly through gravity-fed low-pressure dripper hoses. I pump from the mains tank occasionally, when I have a large watering job like washing the car.

As for filtering and maintenance, each downpipe is fitted with a first-flush diverter. The absence of tall trees on our block makes it unnecessary to have gutter guards, but each tank has a leaf strainer at the opening. Muck sometimes builds up in the leaf strainer (we don’t have many trees, but we have plenty of dust), but this is easy to scrape away. It may be wise to have the tanks suctioned out to clean them, but the need has not become urgent in the 14 years we have been here.

The system has been great. The rainwater level drops a bit by the end of summer, but winter rains have thus far replenished the levels adequately. Twice, the pressure pump has stopped working, but on both occasions, it was repaired quickly and relatively inexpensively; on the second occasion, I also bought a new pump, which has been working well since then. I’m keeping the old one as a backup.

Water tanks in the wet tropics

For Paul and Roberta Michna, who live on 24 hectares of rainforest where the annual rainfall is a whopping 4000 mm, water harvesting and use considerations are a little different than elsewhere. Paul explains their solution.

Deep in the cloud forest of far north Queensland, rainwater collected from our roof supplies all our water needs. Our two 22,500 L tanks were the minimum capacity permitted by our local council; half this would be more than sufficient for our needs.

Site access down a sinuous track passing between ancient trees restricted maximum tank size to a height of just 2600 mm. The tanks are white poly to keep the water cool in the summer heat; the colour also reflects light around the house which is surrounded by dense tree cover. The tanks are located beside the house and form a 45 tonne cyclone barrier in the most vulnerable weather direction.

The biggest challenge under the rainforest canopy is removing leaf litter and pollen, which we do in three stages:

- Our skillion roof directs the rain water into one large gutter covered in coarse mesh leaf guard.

- A self-cleaning angled leaf filter in the downpipe removes any small leafy material.

- The water exiting the tank passes through a fine canister type pre-filter before entering the pump. This filter is checked annually but the gutter and downpipe filters are so effective, it has never really needed cleaning.

Accumulation of algae or moss requires an annual roof clean with mop and soapy water. Pressure is provided using a generator-friendly multistage electric pump feeding a large 80 L pressure tank. Multi-stage pumps have a ‘softer’ startup requiring a lower peak demand from a mains or generator electricity supply. The pressure tank can supply 20 L to 30 L of water through the taps before the pump cuts in for about 30 seconds.

Electrical costs are reduced in two ways:

- There are fewer, softer pump start-ups: the 80 L pressure tank means the pump only starts up a couple of times a day, saving at least 30% on electricity consumption.

- By running longer after each start-up the pump spends a greater portion of its running time operating at its optimal design efficiency.

For waste water treatment, we opted for a modified septic system; alternative systems that rely on reed beds or evaporative composting simply do not work in high humidity. We put our septic weeping bed under the tanks, where the ground would remain dry and infiltration would be possible even in the most torrential rain.

We don’t need tank water for gardening! Our exterior garden is shaded by banana leaves and grows only tropical herbs, fruits and greens; the big leaves divert enough rain to keep the garden happy. Our greenhouse for conventional vegetables has a translucent solid roof and roll-down clear blinds at the ends. Tomatoes, silverbeet, mint and so on get enough moisture from fog, low cloud and spray drift and do not require additional watering for much of the growing season.

The system has worked flawlessly for the past five years. Our biggest ‘oops moment’ was once when we left mopping the roof for two years—algae and moss grow quickly in the rainforest and that cleaning was a hands-and-knees job that took a couple of days.

Stainless steel tanks by the sea

There’s no mains water on Bruny Island, Tasmania, so Gary Lisle and his partner are reliant on their rainwater tanks for all house and garden water needs.

When it came to choosing tanks for their new house in Alonnah on Bruny Island south of Hobart, Gary Lisle made use of Renew’s Tankulator tool to determine the optimum tank size for their projected water usage, given their roof area and the local rainfall. They settled on two 15,000 L tanks plumbed to the house, plus a 3000 L tank for garden use. “As we are very close to the water, we paid the extra for stainless steel tanks,” says Gary, “to ensure they’ll last as long as possible in our coastal environment.”

The tanks are installed on the south wall of their shed and capture water from the 81 m2 shed roof and the 136 m2 house roof. Gary explains the system design: “The shed is near trees so we installed gutter guard, but we didn’t need it on the house gutters as it’s on the windward side of the trees. There are first-flush diverters at the two tank feed-in points on the shed, and I drain these monthly. We have a wet system with poly pipes, but we can open a valve at the low point to drain the wet system.”

To filter their drinking water, they use a stainless steel Berkey countertop water filter system—the filter itself is ceramic charcoal.

A Grundfos CMBE1-44 variable-speed pump delivers the water at pressure to the house. The garden watering tank is connected to the overflow of the main tanks and has a separate pump.

Cheap and easy DIY tanks for garden watering

Luigi Soccio connected a series of recycled plastic barrels to collect water for his garden, dramatically reducing his mains water use.

Four years ago, Luigi Soccio retired and moved from Melbourne to a 650 m2 block a short walk from the centre of Daylesford in central Victoria. To help water his garden, he purchased 22 food-grade plastic barrels for $10 each from a Brunswick food wholesaler who imports olives and other Mediterranean foods.

The barrels are 220 L each and Luigi connected them using irrigation fittings; they are fed from the roof at three points and in turn they feed into a 1000 L tank. A 1100 W garden pump from Aldi is connected to the main tank to deliver water to the garden irrigation system. “It is an incredibly low tech, cheap system that meets my needs and saves water,” says Luigi.

Fine-tuning a suburban rainwater system

Installed as part of a deck build seven years ago, the size of Ian’s 10,400 L squat poly tank was determined by the space available under the deck. In fact, his calculations indicate that twice as much water storage would be optimal: “The rule of thumb I used for tank capacity is twice the maximum monthly volume of rainwater collected. According to the BOM the wettest month on average for us here in Ringwood is May, with about 85 mm of rain. So for our 130 m2 roof (all downpipes are connected to the tank), maximum monthly volume is 11,050 litres, meaning an ideal-sized tank for our location would be 22,100 litres.” [Ed note: this rule of thumb calculation can be checked and fine-tuned using Tankulator, Renew’s free water tank sizing calculator.]

“Despite this, for our family of three and a native, low water use garden this sized tank is enough for us to run the house for about 49 weeks of the year,” Ian says. “We tend to run out just before Christmas and again towards the end of January, and need to rely on the mains supply during those periods. If we were a larger family and/or had a thirstier garden, then we would be more reliant on mains supply.”

There is a Davey pump connected to the tank, and the water runs through a dual-stage 3M Aqua-Pure activated carbon and coconut husk particulate filter system. “The filters need to be replaced about every two to three months; replacement filters are available which are significantly cheaper than the genuine 3M ones,” says Ian. “I buy a package of six full replacements, so I order about a year’s supply each time I purchase.” The tank water supplies the whole house, including the hot water system, except for three cold water taps in the kitchen and bathrooms that supply mains water for drinking. There is also a Davey RainBank linked to a float switch in the tank, that switches to mains water automatically when the tank level runs low.

The garden is watered through the same pump and filter system as the house water supply. “Initially I had a drip system set up in the vegie patch, but we found it too difficult to manage and we kept making holes in the drip system so it became a sprinkler system in places!” laughs Ian. “We’ve now replaced the original beds with wicking beds as our large eucalyptus tree was sucking any water we put on the patch anyway, and other watering is done by hand with a hose.”

Generally, Ian is happy with the setup, although he notes that really only one tap can be run off the pump at any one time, so “if someone flushes the toilet while you’re trying to water the vegies the flow out of the hose drops considerably, and we certainly can’t flush a toilet or turn on the washing machine while someone is in the shower.” He says that his family of three is used to this “one-tap issue”, but nevertheless he’s planning to discuss with a plumber experienced in these installs whether a higher capacity pump, a larger outlet pipe size connecting the filter system to the house, or both, might offer a solution.

Other things he would do differently if he was installing the system again:

- Install the pump and filters in a place that was easier to access. “Currently I have to shimmy between the tank edge and the vertical wall of the deck in order to get to the pump and filters. This was a mistake! Also whenever I replace the filters, the housings need to be rinsed out, which would be a much easier proposition if I had more easy access.”

- Put a good first-flush diverter system on the pipes. He has tried to retrofit something but says it hasn’t worked that well.

- Install a pressure tank between the pump and the filter system to reduce the frequency with which the pump comes on. “I could still retrofit this, but currently the filter system is mounted on the wall directly above the pump, so I have very little real estate to work with.”

Simple and effective

When there is enough water in his tank, Martin Storey buckets water to the washing machine—and gets a workout at the same time.

Martin Storey has a 400 L poly rainwater tank—the largest that would fit in the location—that he paid $80 for and installed himself at his house in Nambour, QLD [check plumbing regulations for your area for tank installations].

It’s not plumbed to the house; he mainly uses the water for the garden, and also to fill the washing machine. “To do this I have to fill up buckets and pour them into the machine as the tank is not high enough for gravity feed,” he explains. “As a personal trainer, I use the bucket lifting as a means of exercise. It’s amazing how many ways you can lift a bucket so as to use different muscles!”

His small, simple system is easy to clean: “Maintenance is easy, I turn the tank on its side every so often and wash out any debris. I don’t have gutter guard or leaf diverters as there are no trees overhanging the roof.”

Further reading

Water saving

Water saving

Nurturing your native garden

Just how much maintenance do you need in a native garden? Robyn Deed gets some tips from landscaper Haydn Barling on how to sustain a beautiful, biodiverse garden in the suburbs.

Read more gardening

gardening

Working with contours

Sarah Coles speaks to Guildford local Louise Balaz-Brown about gardening in tough conditions, the importance of contours and the miracle of sheep manure.

Read more