Off-grid in WA: Riding the trail to sustainable living

Jai Thomas describes his parents’ journey to off-grid living.

This article was first published in Issue 131 (April–June 2015) of Renew magazine.

In 1993, my parents, Sherry and Barrie Thomas, made a life-altering decision to pursue a ‘tree change’, long before that concept came into being. Finding a property in the beautiful Preston Valley of south-west Western Australia, their dream was of a future in the emerging eco-tourism industry, based around their love of the bush and of bicycles. With four children under 10, some might say it was a bold vision!

Twenty-two years after purchasing 100 acres of “rate-absorbing, unpowered, unwatered bushland”, and many ups and downs, they now look back on their journey with pride and are happy to share their story of ‘riding the trail’ to sustainable living.

The early days

Life on the Preston Valley property started in a tent at weekends. With a six-day bike shop business in town and four children in primary school, even just getting to the place one day a week was a challenge. Then, the retail slowdown of the mid-90s hit the bike business hard. With both time and finance in short supply, Sherry and Barrie decided to start small, with an owner-designed and owner-built weekender cabin.

In 1995, with a site selected, Sherry designed the 9 m x 5 m two-storey cabin with an open-plan kitchen and lounge room downstairs and loft bedroom upstairs. They used Colorbond and Hardiflex cladding on recycled jarrah stud walls, built around jarrah poles sourced from the property.

Even though the cabin was small in footprint, the one-day-a-week approach meant progress was painfully slow. Lessons were plentiful. The jarrah used in the wall frames was so hard it was virtually impossible to hammer a nail without a pre-drilled guide hole; as a result, the decision was later made to use pine frames when building the main house! They scoured all over for construction materials—from demolitions, discards after renovations and saleyards. Only rarely, given their financial situation, did my parents purchase new.

Their first stand-alone power system (SAPS), a 12-volt system featuring just three 85 W panels and 2.4 kWh of deep-cycle lead-acid batteries, almost broke the budget before the building began. Barrie, an electrician by trade, wired in 6-volt bicycle headlights, the very first LEDs of their breed, in series of two. Fitted to old sets of bicycle handlebars mounted on the walls, this gave them (characterful!) lights at night, but nothing more.

The old Honda diesel generator worked hard during construction, and after 12 long years the cabin was finally born, albeit not quite finished.

Developing Kambarang

For the Nyoongar people of south-west WA, Kambarang is the name given to the wildflower season in October and November, one of six distinct seasons, marked by the emergence of the spectacular yellows of the cowslip orchid and native buttercup. This time of year is one of the most striking in the Preston Valley, so my parents lent this name to their property.

Building the cabin at Kambarang was the first step in their plans. Their vision for the 100 acres was for eco-tourism based around the bicycle trails and the beauty of the wildflowers.

The early mountain biking trails were short, about 3 km in total, mostly born from kangaroo tracks. Over time, they’ve developed the trails (using erosion-friendly construction) into over 14 km of single-track trails weaving their way across Kambarang and catering for mountain bikers from novices through to seasoned pros. As hoped, the trails have become a tourism drawcard, and the property even hosted its first state series event in 2005.

Building the house

In December 2007, some 14 years after purchasing the property, construction commenced in earnest on the house that would become my parents’ dream home. With us children having finished school, they wound up the bike shop after 20 years and sold the shop premises to fund construction.

Sherry’s design approach had evolved over the years, but, as with the cabin, centred around passive solar design. The design features a north-facing frontage with high ceilings, verandah to the east and no windows on the west wall. Sherry did allow herself one design indulgence in the stunning curved roof.

They selected internal rammed earth feature walls for thermal mass, surrounded by Timbercrete bricks and Hardiflex Scyon clad pine stud-walls supported by jarrah posts. These striking jarrah posts, 200mm x 200mm, were sourced from the property, milled some years prior to construction, sanded and finished in Organoil. Jarrah poles holding up a portion of the roof are from trees felled by a mini-tornado in the summer of 2005.

Slate tiles, underslab vent pipes to the kitchen and insulation in the walls (Autex Greenstuff recycled polyester) and under the roof (both Autex and Anticon) help to keep the need for additional heating and cooling to a minimum. The Everhot wood stove bridges the gap in winter. The Timbercrete bricks, made by local Donnybrook couple David and Lynelle Leatherard, and used on west and south walls, have also proven to be remarkable thermal insulators.

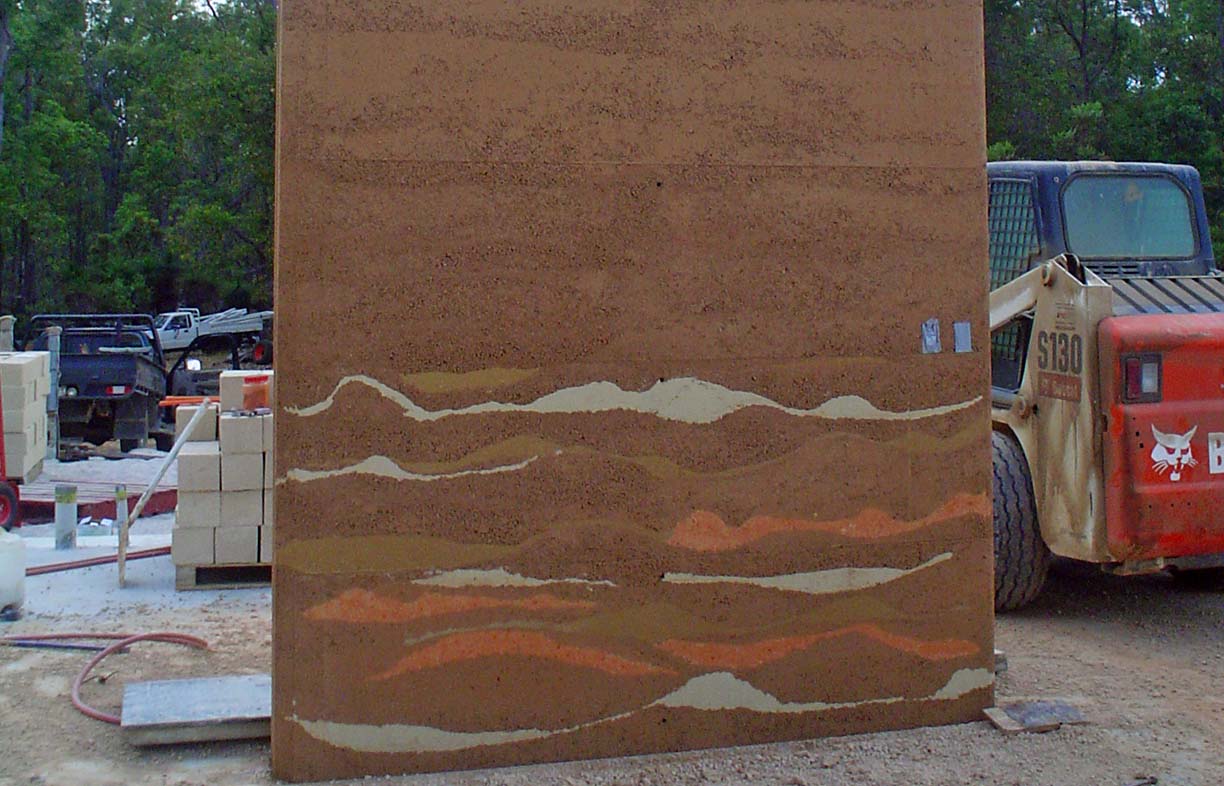

The use of rammed earth, done with the help of Affordable Rammed Earth of Boyup Brook and made up of 75 % gravel, 25 % lime and cement stabiliser, not only provides attractive feature walls, but also a thermal mass that helps keep the house warm in winter and cool during summer. The earth on-site was overly ‘bony’—the stones in the gravel were too large to be used—so earth was sourced from nearby Mumballyup, some 10 km down the road.

To add to the effect, Sherry decided to use a finish she had seen many years prior, using various sands in the mix to give flowing bands of colour across the rammed earth. This technique requires preparation, fast hands and a fair bit of guesswork behind the formwork. Adding to the equation, construction was during February, and the worksite was so hot that the earth was ‘setting’ too quickly, meaning any notions of an even and calculated sand layering went out the window. However, Sherry loves the resulting random, meandering flow—and the one panel that does have even waves is her least favourite.

Despite having freed up time from the bike shop to focus on construction, progress was again slow. My parents relied on expert advice from a retired builder friend, Gino De Coppi, who insisted on a quality finish and helped them avoid basic mistakes.

Since moving in during November 2010, the house’s performance has been beyond their expectations. A second wood heater had been planned for winter heating. But Sherry says, “Luckily it wasn’t installed as we don’t need it. Instead we just keep the Everhot stove burning longer and put on an extra jumper if needed (recommend good quality ugg boots too!).”

Summer heat is a problem if they have a run of more than about seven days of 35°C or above. Internal rammed earth walls get warm after about a week and the inside temperature can get up to 30 °C then. But “if it’s 42 °C+ outside, 30 °C doesn’t seem so bad when you come inside!” That happens once or twice a year.

Hopefully as their gardens become more established, that will be mitigated somewhat too. Still, they just bought a small portable air conditioner for Sherry’s office after the last hot week. She says, “Let’s face it, we only use it when we’ve got plenty of power anyway— and I’m getting old.”

Power supply for the main house

In 2008, back-of-envelope estimates from the electricity network service provider put network connection costs in excess of $100,000, with corridor clearing and ongoing maintenance of poles and wires both also required. So the decision to install a SAPS was an easy one, despite the expense of the technology at that time.

The government’s Renewable Remote Power Generation scheme was in full swing, intended to favour off-grid installations over network augmentation, and it matched my parents’ investment dollar for dollar (total cost of $54,000). These days, the price of solar PV and the emerging battery market mean that such investments can stand up on their own financially in these rural situations— with the added advantages of providing a more reliable and better quality power supply than long network spur lines, and reducing the risk of network-born bushfires.

In selecting their SAPS, my parents chose to go one step further. Through the use of passive solar principles in the house design, LED lighting, carefully selected appliances and a solar water heater combined with a wetback stove to avoid an electric booster, they were able to reduce their electrical load and eliminate the need for a backup diesel generator entirely. Their 48 V system, consisting of 2.3kW of PV panels, 49kWh of batteries, an Australian-made Selectronic 3600W inverter and Plasmatronics PL60 regulator, has powered the site fossil-fuel-free since February 2008.

Thus, their renewable fraction is 100 %, with perhaps a day or two in the year where their load profile forcibly shrinks to fit available supply. Put simply, on these rare nights, they have an early night!

Sherry describes it as “almost a symbiotic relationship with your power supply, an awareness of energy flows in and out of your batteries. You learn to modify your behaviour very quickly and it is very easy to live with”. The bar fridge gets turned off in winter, dishes are done by hand, but, for the most part, living in tune with their electricity supply has simply become second nature.

Living in, and sharing, the bush

Living in the bush is not without its challenges. In a changing climate, the threat of bushfires has increased. A fire-sprinkler system has been installed in the main house and fire-retardant plant barriers placed up to 30 metres around the house site. Water supply comes from two rainwater tanks of 75,000 litres and 45,000 litres–the second installed as a result of running very low during the first summer living in the house—and tank depth is front of mind in the summer months. However, they see these as small issues when compared with the joy of bush life and the sharing of the space and its stories.

Slowing down doesn’t seem to be in their nature. My parents have also installed a corrugated iron shed, powered from the single SAPS, and this has enabled Barrie to re-invent the bike shop at Kambarang, with the added element of a bike maintenance training centre. In the shop, he also hand builds bicycle wheels using a traditional spoke lacing method that, in most places, has long gone the way of computer-driven machines.

The original cabin is now used as a holiday rental, and Sherry takes any interested visitors on walks through the property, pointing out wildflowers, which include the uncommon butterfly and spider orchids.

They are keen to share their joy in living on the property, in the bush and without fossil fuels. “We just love it, waking up here each day,” says Sherry. “I challenge anyone with the same vision to pursue it. My message is simple—you can do it, if you want it enough.”

This article was first published in Issue 131 (April–June 2015) of Renew magazine.

DIY

DIY

Deleting the genset

If you have the need for the occasional use of a generator, then why not replace it with a much cleaner battery backup system instead? Lance Turner explains how.

Read more Renewable grid

Renewable grid

Is a floating solar boom about to begin?

Rob McCann investigates the world of floating solar energy systems.

Read more Products

Products

Product profile: Portable solar recharge hubs

Providing device recharging for events or outdoor areas with no access to electricity can be difficult, but the Furnicharge Freedom Hub makes it simple.

Read more